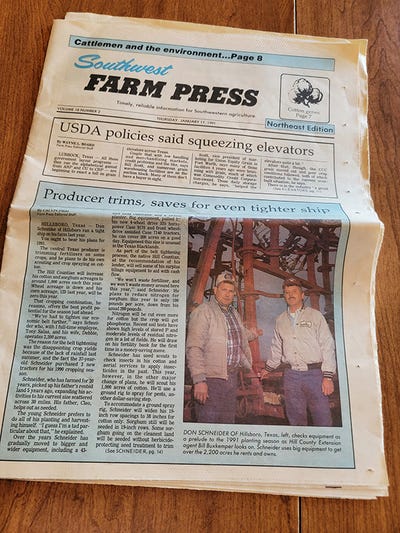

Bryan and Don Schneider, Hill County, Texas, producers.Shelley E. Huguley

When Don Schneider was featured in the January 17, 1991-issue of Southwest Farm Press, he said he was further tightening the farm's "economic belt" following a year of drought and "disappointing crop yields."

Flash forward 31 years, and his son, Bryan, who wasn't alive at the time of the interview, is cinching that same belt, not because of last year's drought, but because of the current one, along with inflated fuel and production costs and rising land values.

"2021 was a dream year," Bryan says. Last year was one of those years that, "everything went well. Prices were good and we were fortunate that we had purchased inputs early when they were cheap. By the time harvest came, the price of commodities was high."

"It rained all the time," Don says of the 2021 season. "Cotton can hardly get too much when it gets to a certain stage. It just loves it."

Last season, the Schneiders averaged 2 bales to the acre and 140 bushels of corn per acre. "We had some of the best yields we've ever had," Bryan says.

Don and Bryan farm together but also separately in Hill County, Texas. "We help each other out," Bryan says.

"I've got arthritis pretty bad, so he does the hard part," Don says. "We make it work as we go."

In the 90s, Don was growing sorghum, cotton, and corn. He told then-editor Calvin Pigg, "We won't waste fertilizer, and we won't waste money around here this year," a philosophy he's passed along to his son.

"We're not cutting back on our fertilizer because we weren't wasting any to start with," Bryan says. "We can't cut something we were already watching closely."

Bryan says they won't spray Roundup across the board. "In years past, Roundup was so cheap you'd throw it in just to kill a little bit of stuff, but now, you've got to be more careful. It's a lot more expensive."

Roundup that was $17 per gallon last year is as high as $50 per gallon this year, Don says.

"I paid $205 for some fertilizer last year. It's over $600 this year, so three times as high. It's not easy," Bryan adds.

Bryan and Don Schneider farm together near the Malone area. (Photos by Shelley E. Huguley)

Don has been farming since 1970. "There's been price hikes but never this drastic. Back when I bought my first tractor, I paid 18% interest for my operating loan on my tractor and paid it off in two years. Even though interest was high, everything was kind of give and take." That's not the case today.

Bryan recently visited with a college friend who sells chemical and seed. He said they talked about how farming is a gamble but now, "you're at the high rollers table. The risk is a lot higher, but you can have a higher reward too, if you hit a big crop."

Strategy

Don and Bryan rotate cotton and corn. Bryan says this year's strategy is to "stick with what you've always done and hope to make a good crop."

"The only way we can really do this (pay inflated prices) is because we made such a good crop last year," Don says. "But we're not going to be able to do this two years in a row. We can't pay that much for fertilizer and chemicals. If cotton or corn doesn't go way up to offset it, it's going to be hard to do.

“And I don't know what banks are going to do because you have to have crop insurance, but that won't pay as much as a good crop."

Initially, Don had hoped to save last year's surplus to purchase some family land. "My mom is 90, so I'm going to buy her land. I should have bought it five years ago, but I've got siblings, so I wanted to be fair.

"I didn't want to use any of that money we had leftover. I don't know how it's going to work if we have two more years like this."

What they're not going to do is purchase equipment. "It's not something you want to do when you're uncertain about things. So, we're sticking to our input costs and keeping it as low as we can," Bryan says.

Bryan has already applied chemical to treat pigweed and broadleafs. Don is putting his on hold and will likely only make one trip.

The drought has them concerned about the efficacy of those herbicides. "We're not getting very much rain and you have to have rain to make those chemicals work," Don says. "We put some out in November, and it never rained. So, it's hard to make a chemical work like that."

Fertilizer

If the drought persists, Bryan says they won't apply all their fertilizer. "We put half our fertilizer out in front and then we come back and put out half in season, while the crop's growing. If it doesn't start raining, we're not going to do that. That's half the money on fertilizer we don't have to put out if things aren't looking good. That's one good thing about splitting up your fertilizer."

On this day, it smelled like rain. It looked like rain. Unfortunately, it did not rain. But that didn't last forever. The Schneider's finally received about 1.5-2 inches of rain Monday, April 25.

Don and Bryan strip till. In the past they applied fertilizer in the fall and hoped it would still be there in June. Now, they spoon-feed it. "You go right back with your seed where that fertilizer was. Actually, you could cut back some (fertilizer) because it's right there where the root system is, but we're scared to. But that will carry you to make a pretty good crop if you have to -- if it rains."

Marketing

Don and Bryan follow a marketing philosophy Bryan learned while earning his degree at Texas A&M University. Rather than waiting to see what the price is going to be at harvest, a professor recommended marketing the crop throughout the year. "You're never going to hit the low and you're never going hit the high either, but you're going to be somewhere in the middle. I try to do some of that without having too much forward contracted, not knowing what I'm going to have," Bryan explains.

"As high as the input costs are, you've got to cover your bases at some point, even this early, because you never know what it's going to be like come harvest."

Cattle

The Schneiders also raise cattle. "Our Bermudagrass is starting to green up, but we have no winter grass. I mean none," Bryan said. "That first cutting of hay isn't going to be here this year. It's going to be later in the year. We haven't put fertilizer out yet because it hasn't been raining."

If it doesn't rain, they'll bale corn stalks. "I hope we don't have to, but you never know. At least we have an option. A lot of people don't have options in that situation. They only have pasture."

They plan to fertilize enough to get the number of bales they need to get their cows through the winter. "If we have to buy hay, it's going to be more expensive. So, we'll be fertilizing ours because we need a certain amount. We're not necessarily wanting to sell any, but we know we need x-amount."

Challenges

Coupled with drought and input challenges, producers like the Schneiders are dealing with urban sprawl, high land values and the installation of alternative energy sources, some of which take agricultural land out of production.

"I'm going to lose about 250 acres of rented land to solar," Don says.

"That's something I'm going to be fighting throughout my lifetime," Bryan adds. "The metroplex is coming south. It's gone so far north that it can't go north anymore. It's got to start coming south. We are fighting windmills and solar panels and urban sprawl."

Bryan says income from wind turbines on a farm he recently purchased helps make his land payment. "I think the windmills are going to be our saving grace because it keeps people from moving here and it keeps solar panels from going up. You can farm around a windmill; you can't farm around solar panels and houses."

Read more about:

Wind TurbinesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like