A farmer diagnosed with high blood pressure has prescriptions for three different medications. Each pill bottle offers the instructions to “take daily.” With three pills in the mouth and a quick swig of coffee in the morning, the farmer leaves the house. By midmorning, he is climbing the grain bin. Halfway up, he feels light-headed and dizzy. He grabs ahold of the ladder to steady himself.

Kelly Cochran knows this scenario all too well. She says dizziness can happen because farmers take all three medicines at one time.

The University of Missouri-Kansas City clinical associate professor is helping future rural pharmacists recognize these types of issues farmers may face with prescription medication.

Farming is already one of the riskiest occupations, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the National Safety Council. Adding medications to the mix can increase those risks for farmers working with equipment and livestock.

Cochran says taking medicine may increase the risk of farm injury by two- to fourfold.

That risk goes up as farms get larger and the average age of farmers nears 60, adds Karen Funkenbusch, University of Missouri Extension health and safety specialist and Missouri AgrAbility director.

Adding to the problem is that at least four counties in northern Missouri have no pharmacies. In some areas, residents are 10 miles or more away from the nearest drugstore, she explains. And there is even a greater distance to travel for primary care doctors and specialists.

“In many rural Missouri areas, pharmacists fill the health care gap,” Cochran says. “They are the first line of defense in farm health and safety.”

So, she is working with not only pharmacists, but also farmers to identify medical risks through the UMKC School of Pharmacy’s Pharm to Farm program and a partnership with the Missouri AgrAbility Project.

Background of care

Cochran grew up in Indiana surrounded by veterinarians. She showed beef cattle in 4-H and was a district officer in FFA. Her family owns one of the oldest Angus herds in the state. However, the Indiana farm girl was more interested in how to administer medicine to the human component of agriculture. So, she chose the field of pharmacy.

“I am aware of the challenges to access health care in rural America,” she says. “I care about these areas and the people in them. I grew up there.”

In Missouri, 98 of the 101 rural counties are considered to have a primary care health professional shortage by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Cochran saw how farmers and ranchers would see their primary care provider infrequently. “However, they see their local pharmacist to pick up refills either weekly or monthly,” she says. “These are prime opportunities to build a relationship and have questions or concerns addressed. We just need to train the next generation of pharmacists how to help our farmers and ranchers.”

In the classroom

Cochran is a clinical associate professor with UMKC, which has satellite offices on the Columbia campus and at Missouri State University in Springfield.

“We start by telling them that their first jobs as pharmacists may be in a rural community,” she says. “We try to educate them on the risks surrounding farming.”

Students learn to apply drug information knowledge, so farmers and ranchers can get the most benefit out of the medication while limiting their risks from potential side effects.

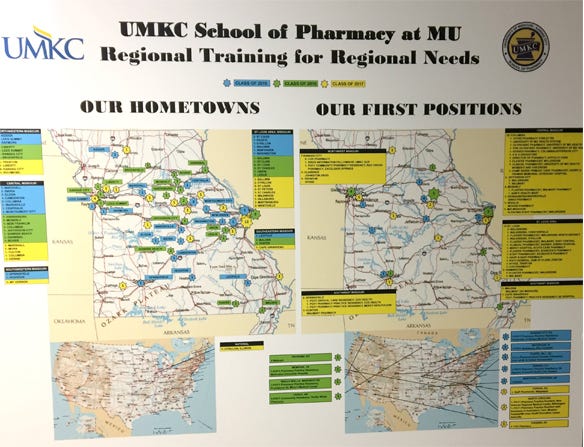

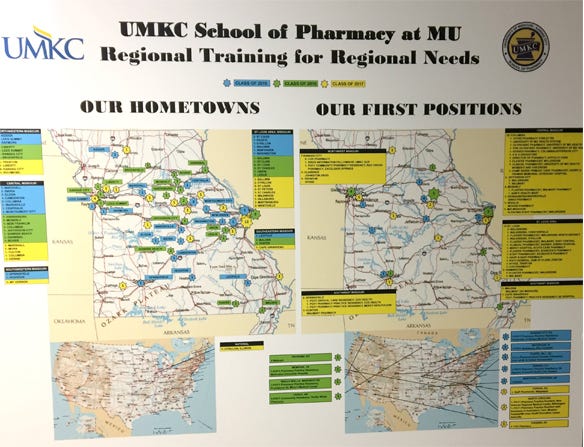

STATEWIDE EFFORT: Some graduates in the UMKC pharmacy program will likely serve in a small town. The Pharm to Farm program helps them understand their surroundings and clients.

Pharm to Farm also talks about farm life and farm values, like independence, pride, thrift, skepticism and a strong work ethic. Understanding these aspects, Cochran says, can help these future pharmacists be a trusted adviser in their rural communities.

“We teach pharmacists how to talk with farmers about making changes in their medicine routine to make sure they are safe around their operation,” she adds. “But we always work in conjunction with their primary care provider.”

On the farm

Pharm to Farm offers on-site farmstead assessments to find and lower risks associated with medicines.

Since many of Cochran’s students do not have an agriculture background, she takes them along on farm visits. “We have met with people in the barn, farm field or at their kitchen table,” she says.

During on-site visits, they check medicines and talk about their risks. They discuss their workday and offer tips for when and how to take the medicine to reduce downtime.

ON THE FARM: Two participants in the Pharm to Farm program, Kerri Shipley (left) and Jennifer Richter, visit a farm to help the owner determine when it is best to take medicine given his workload.

ON THE FARM: Two participants in the Pharm to Farm program, Kerri Shipley (left) and Jennifer Richter, visit a farm to help the owner determine when it is best to take medicine given his workload.

Farmers can sign up for an on-site visit to review medication directly with Cochran or through the Missouri AgrAbility Project.

“My goal is to make sure our students are prepared to take care of these folks,” Cochran says. “It is a population that I care deeply about. It is a population we should all care about.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like