A cold, wet spring that caused record slow corn planting has the 2019 crop squarely behind the 8-ball. To recover lost potential, production must run the table with near-perfect conditions the rest of the growing season. Otherwise, a smaller crop could wipe out much of the surplus USDA forecasts for the coming year.

While the slow start doesn’t doom the crop, the unusual political and economic environment of 2019 could make recovery more difficult than in other years with major delays.

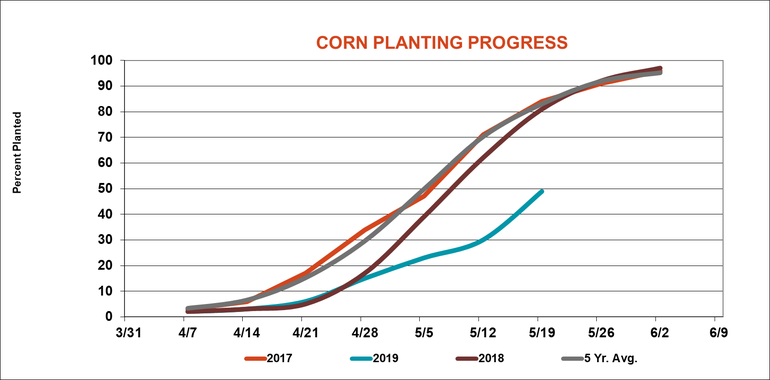

USDA reported only 49% of the crop planted as of Sunday, a key metric for corn traders, who like to see 85% of fields in by the end of the 20th week of the year.

Late planting can have three impacts on production:

Lost acreage: Final planted acreage tends to be less than March intentions reported by USDA in late years. Traders already roundly dismissed USDA’s March 29 planting estimate because the most of the agency’s survey was conducted before the “bomb cyclone” that flooded Nebraska, Iowa and Missouri, adding moisture in other states. Rains haven’t let up either.

Increased abandonment. Late planting can mean late development, forcing some fields planted for grain to be harvested for sileage or grazed instead.

Lower yield potential. Corn planted later in May or into June can yield less, especially if growers switch to shorter-season varieties.

To gauge the impact of late planting on this year’s crop, we looked at results for eight key states included in a popular model for forecasting yields developed by USDA economists. Those states include Illinois, Iowa, Indiana, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio and South Dakota. When weighted by March planting intentions, progress as of May 15 was 35%, less than half the average since 1980. The pace wasn’t the slowest ever over those four decades, but it was close. Farmers planted less by mid-May only in the great flood year of 1993, and in 1995, which turned out to be one of the most unusual years on record.

Here’s how planting progress could impact production potential this year.

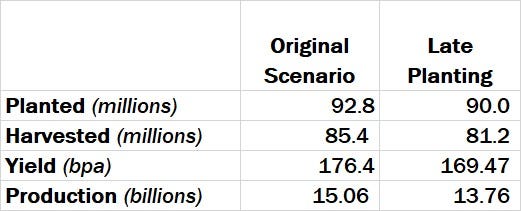

Planted acreage could fall to 90 million, 2.8 million less than USDA estimated in March

Abandonment could run 10%, compared to about 8% recently. That could decrease harvested acres to 81.2 million, compared to USDA’s current estimate of 85.4 million.

Yield potential with normal summer weather could drop nearly 7 bushels per acre, from 176.4 to 169.5 bpa.

Added together, these factors would produce a crop of 13.8 billion bushels, not the 15.1 billion bushel-plus under USDA’s original acreage assumptions with normal weather and planting progress.

USDA May 10 estimated leftover supplies at the start of the 2019 marketing year will be 2.095 billion bushels. A crop that’s 1.3 billion bushels shorter would threaten to take ending stocks down to dangerously low levels unless prices rose enough to ration usage and maintain a surplus.

Making predictions all the more difficult is the unusual backdrop for the 2019 growing season. Growers face crucial decisions as the final planting dates approach that begin to reduce crop insurance coverage. Taking prevent plant on corn acres may not bring enough to cover costs already invested and could forfeit potential for the government tariff compensation package. Corn growers only got a penny a bushel under the 2018 formula, a figure that’s likely to increase this year. But 2018 payments were made only on harvested bushels.

Switching to soybeans may not seem like a better alternative, given the impact of the trade war on prices. But the combination of crop insurance, government farm program choices, including PLC and ARC, and new tariff aid could make soybeans profitable.

To be sure, slow planting doesn’t guarantee lower acres and yields or increased abandonment. But again, price dynamics this year could come into play.

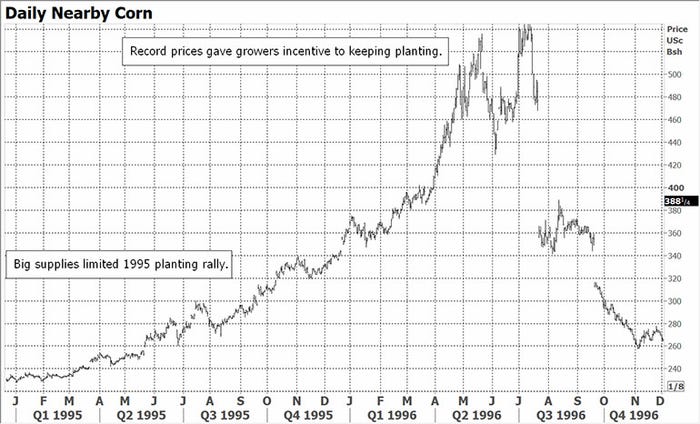

In 1995 for example, farmers planted 3.8 million fewer acres than March intentions, a drop of more than 5% when just 31% was planted in the eight key states May 15. But prices barely topped $2.70 on the planting rally, thanks to good supplies following the first 10-billion-bushel corn crop in 1994.

Searing heat reduced yields in 1995 and prices began to rally after harvest as supplies grew tighter. Planting was a little faster the following year, but it was still the fifth slowest. Acreage fell less than 1% from March intentions. One difference: Futures rallied to a then-record high, topping $5 for the first time, providing growers plenty of incentive to plant more and abandon less. Yields also turned out better than normal in 1996, as they have in some other years when planting was a struggle.

This week’s slow planting progress, and forecasts for more rain into June, should reset the table for the 2019 summer selling season. Still, there’s always potential for the market to scratch.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like