With 64,000 square feet of growing space, Springworks Farm in Lisbon, Maine, is a place where plants and fish grow in aquaponics harmony.

“So it’s one big ecosystem, and we’re essentially stewards of it,” says Trevor Kenkel, founder and president of Springworks.

He started tinkering with aquaponics while in high school in Montana, where he grew up. Having grown up around farming and ranching in Big Sky Country, Kenkel wanted to do something that mimicked more natural systems for growing crops.

He started a little organic garden and got chickens, “but eventually I wanted to find a way to grow year-round,” he says. “In a place like Montana, aquaponics was that solution to be able to grow organically in a controlled environment where it can be done year-round.”

Kenkel built a greenhouse system in his backyard to grow crops for his family, but he ended up producing a lot more than he knew what to do with. He started selling crops to some restaurants, the boost he needed to get the business off the ground.

A few folks liked his idea of aquaponics, he says, and in 2012, Springworks Farm, with the help of investors, started as a small, 6,000-square-foot hoophouse. At 18 years old, he was running a farm and attending college.

Unique growing system

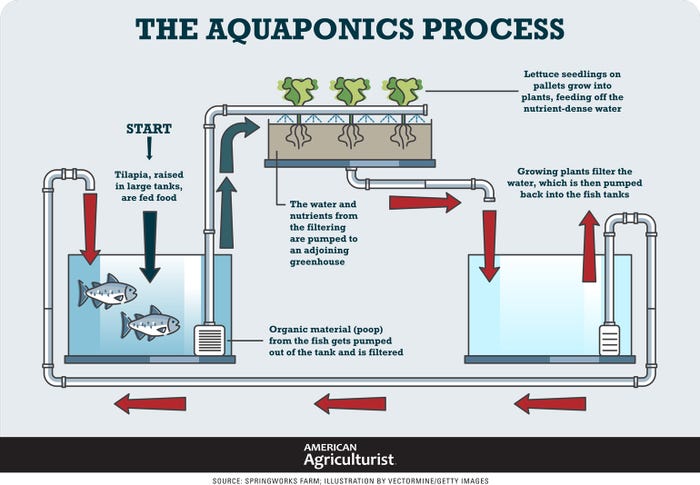

Aquaponics combines fish and plants in a recirculating water-based system. The plants grow on platforms over water fed by nutrients provided by the fish. The tilapia fish grow in separate tanks away from the hoophouses. During the growing process, the plants end up cleaning the water, which is then pumped out and recirculated back to the fish.

Young tilapia — known as fry — weighing less than 1 gram are flown in from a supplier. The fish are grown for 10 months, moving from container to container before getting to market size, where they’re sold to a local fish market.

“They are really important as the fertilizer engine behind the system,” Kenkel says, adding that they produce about 200,000 pounds of fish a year, a second revenue stream for the business.

Initially, Kenkel and his team marketed almost exclusively to food service. But eventually, they switched their marketing to direct retail and wholesale accounts.

“Initially, we planned to grow a lot more things,” he says. “So we started out growing 20 different things through the facility early. All kinds of different herbs like basil and cilantro, and all done through aquaponics.”

Food deliveries to restaurants were done in a modest refrigerated van. But Kenkel quickly found out that it was better to focus on a few things rather than many things. He downsized the product line to focus on lettuce — Boston bibb, romaine and green leaf. Having fewer products meant that it was unlikely that he’d run out of product for his customers.

"I think every crop has its own kind of unique idiosyncrasies that can be challenging to manage,” Kenkel says. “Every crop that you add … adds variability into your overall production and operation, and I think that's important.”

The plan worked. Springworks eventually scored a contract supplying Whole Foods in the region, and it became the sole supplier of organic green leaf lettuce for Hannafords, a local grocery store chain.

Greens are cut four times a week, and Kenkel estimates that he and his team produce more than 3 million heads of lettuce a year.

Bullish expansion

As the business has expanded so have Kenkel’s goals: He wants to replace commodity greens grown in California with more locally grown greens produced in aquaponics greenhouses.

The first years of the business, he focused on perfecting the nutrient solution within the system. The tilapia provide the nutrients for the plants, but Kenkel tinkered with ways of filtering those nutrients so the plants would grow faster and better. Once he and his team got more consistency year-round, they were primed to expand.

The facility now has three greenhouses: the original 8,000-square-foot greenhouse, a second 18,000-square-foot facility, and a third 40,000-square-foot greenhouse.

Lettuce is king at Springworks Farm. More than 3 million heads of lettuce are produced a year at the farm, with four cuttings per week.

"We very quickly proved that we could compete in quality, price point, all of that, with the product coming from the West Coast, and that indicated to us the opportunity is not, as say, as a niche local provider, but truly as a broad produce producer,” Kenkel says, “and really being able to produce a large portion of our customers’ produce section.”

An even bigger expansion is planned for the next five years: 500,000 square feet of growing space.

“There’s so much opportunity with our current customer base and within the Northeast produce market,” Kenkel says.

Young team

Of course, growing a business depends on the right people. For Kenkel, those people have included family members and friends who are as dedicated to proving the aquaponics model as they are growing the business.

His older sister, Sierra, joined the company four years ago to run the company’s farm stand. She is now vice president, cultivating relationships on the sales side.

Tilapia are the fertilizer engines at Springworks Farm. They are shipped to the farm as tiny fry and spend 10 months growing. Once mature, they are sold to a local fish market, offering a second revenue stream for the farm.

Emily Donaldson, director of business development, went to Mount Holyoke College but did an exchange at Dartmouth College and has a law degree. She met Kenkel while in college through a friend. While at Dartmouth, she did research on water-based ag systems, and even though she could become a lawyer full time, she joined the business a year ago.

It’s a young team that runs the business. “The way we grow uses significantly less resources, and I think that's what drives our team," Kenkel says. But growing in an aquaponics setting is still hard work.

"Everybody here works very hard. Not only do we have to get folks excited about it, but they have to genuinely want to put that work in, too, and that sometimes can be difficult," he says. “We get a fair amount of people that are like, oh man, I'd love to work in this operation. They have their first couple of days, and they're like, um, maybe I'll buy the product instead. The work we do is, generally speaking, ergonomic relative to say having to pick it at ground level … but it's still farming at the end of the day. It's tough work.”

While lettuce is still king, Kenkel and his team are starting to grow some herbs again. But he’s taking his time.

"We have been very intentional about scaling,” he says. “Over the years, there's been opportunity to grow a lot faster, and earlier, in the company’s life cycle. And we generally would only grow as fast as we felt that we could because not only were we scaling a technology, there's everything else that goes with a growing business, too. Now we're scaling more rapidly, but it's only after putting in seven years of figuring the system out, getting our supply chain right, understanding our customers and the products that we grow.”

"It's not always about gross productivity; it's about what do people actually want," he says. “What does quality and what does value mean to the consumers that are buying our product?”

Read more about:

Young FarmerAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like