These days, the word "resiliency" gets used a lot — and in many different contexts. It's a fairly broad term, and it can mean several things in the context of agriculture alone. At the recent Driftless Regional Beef Conference, Kevin Bernhardt, professor of agribusiness at University of Wisconsin-Platteville, helped break down what resilience means for farmers and ranchers.

While the dictionary defines resilience as "the power or ability to return to the original form after being bent, compressed or stretched," Bernhardt said a more appropriate definition for agriculture might be: “the power or ability to return to normal business operations and profitability after a risk has occurred in the operation."

These risks include low prices, weather disasters, death of a primary manager, loss of markets and increased interest rates.

"Can I do something with respect to my operation and the decision I make and the mitigation strategies I put in place that will help my operation continue on even if these punches happen?" Bernhardt said. "Farm resiliency is the operation being able to take that punch."

But it also goes beyond being able to "take the punch." It's also about building the capacity of yourself as a manager, the capacity of those who are advisers to the operation, the capacity of employees, and the capacity of the farm's economic viability.

Bottom of the cycle

Bernhardt noted that often, that "punch" is delivered due to the cyclical nature of agriculture. And it's important to note this cycle brings a cycle of emotions.

"As we come out of a very low profitability period, we might start to build some optimism. That works its way to excitement. And when we hit those high profitable years that happen occasionally, it just becomes downright euphoria," he said.

"Of course, that cycle turns, and once everybody starts producing too much, we start getting surpluses, and we turn that corner. We're going to deny that for a while. We're going to assume things are going to come back up," he added. "But, of course, they don't right away. We start getting a little fearful, we start getting a little panicky, as we see the red starting to build up in our financials. And we eventually work our way down to where it's downright depressing."

Protecting against what Bernhardt refers to as "the mud" in the low end of these agriculture cycles is a destination, and it involves a management process — building farm resiliency isn't done overnight.

Spokes of a wheel

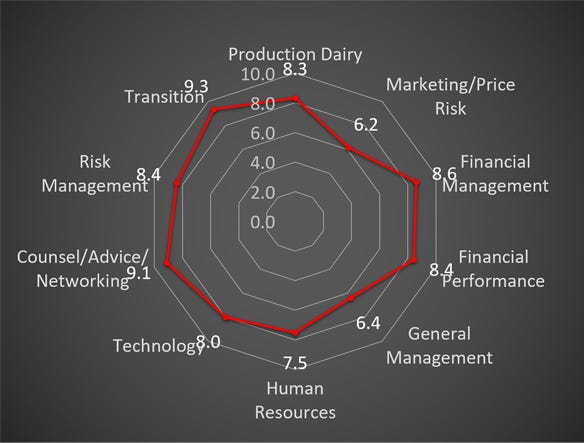

Bernhardt encourages growers to envision farm resilience as a kind of wheel, with spokes made up of areas of management. These spokes include risks — legal risk, third-party risk, production risk, financial risk, marketing risk and human resource risk. It also includes self-improvement, networking, and gaining counsel or advice from other people, and "keeping up" — in other words, staying up to date with the latest practices, technologies and research.

If the low part of the cycle is mud, Bernhardt noted a round wheel is ideal for getting through it.

"In other words, it's not good enough to just be good at legal risk and be good at third-party risk if I don't ever pay any attention to production, financial or marketing," he said. "What happens to our wheel if we have spokes that we're not paying attention to? It becomes square."

"We also want our wheel to be big," he added. "In other words, that means paying significant attention to all of the management areas — not just something that's on my list of things to do, but things I've actually evaluated, I've improved it on my operation, and I'm continuing to take a look at it each and every year to see how I can improve it even more."

Wheel in motion

Finally, Bernhardt said, the wheel must have air in the tire — that is, plans must be put into action.

"We need to make things happen. It starts with having an idea. It starts with some good, strong planning and preparation," he said. "But if we do all that and we don't implement it, then we haven't really gotten anywhere. We haven't improved the resiliency of our operation."

Bernhardt encourages producers to follow what he calls the "Plan, Do, Check and Act" process.

"Planning is identifying the needs you have, setting whatever goals you want to achieve. The 'do' part is you pull that trigger. You actually do it. You buy that insurance. You actually go to that conference and learn a new technique. You actually go and talk to someone about direct marketing your beef," he said. "The 'check' part is asking, 'Did it work?' Not every idea is a good one. Not every idea that we put together actually ends up working the way we want it to work. We always want to check our results. Is it doing what I wanted it to do? If not, why not? ... Then we act on that. We find the root causes of whatever that problem is, we adjust, and we go back again."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like