In the movie “A Few Good Men,” Tom Cruise’s character sarcastically utters: “And the hits keep on coming.” That movie is now 30 years old, but the line feels quite prescient, given recent circumstances.

First, a global pandemic caused rolling work stoppages and shutdowns across the globe. That led to severe supply chain shortages, which have yet to be completely sorted out. After massive government payments, we have the highest inflation in a generation.

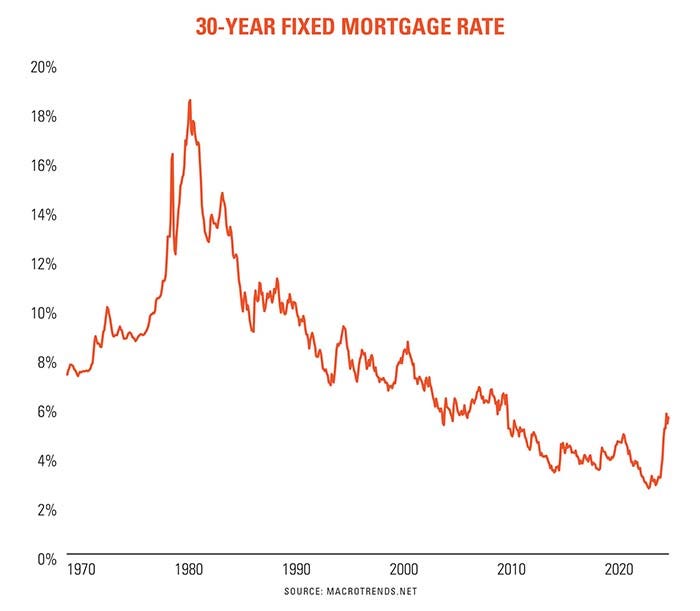

Now, the Federal Reserve has stepped in with an aggressive interest rate strategy to tamp down that inflation. As of this writing, the Fed has bumped up interest rates four times in 2022 to a target range of 2.25% to 2.5%.

What does that mean in practical terms? A 2.5% hike equates to an extra $250 in interest per year for every $10,000 you borrow.

Ask 2 questions

The current situation begs two important questions. First, is it too late to refinance debt after interest rates have already risen sharply in recent months? And second, will rising interest rates reach a point that will cause farmland values to crumble, as they did in the 1980s?

The first question is easy enough to answer, says Tanner Ehmke, economist with CoBank’s Knowledge Exchange research division.

“If the Fed will follow through with raising rates, which is probable, then lock in rates today,” he says. “That’s the most you can do to manage that risk. And if you have adjustable-rate loans, try to move them to fixed rate. Hedge against higher interest rates before they go up more.”

In other words, even though loan rates have risen sharply in 2022, they’re still at historically low levels.

The second question is a bit trickier to answer: How, exactly, will current interest rate trends

affect farmland values?

Experts don’t quite agree but do admit there are a lot of factors in flux that haven’t been sorted out.

Kevin McNew, chief economist with Farmers Business Network, says a lot of farmers still harbor bad feelings about the 1980s when they saw farmland values crash, but it may be premature to worry about an encore.

“We don’t think interest rates are going to get high enough to derail the farmland market,” he says. “We’d need to see interest rates well above double digits before we worry about that.”

The 1980s presented a worst-of-both-worlds situation — commodity prices were low, while interest rates were well above inflation rates, which proved to be a deadly combination for farmland values.

“Neither condition exists today,” McNew notes.

Some experts (McNew included) think farmland values could stabilize or see modest gains in 2023. Others speculate that a moderate drop of 20% or more is possible next year. But, as Ehmke points out, it’s currently too early to tell.

“Who knows?” he says, recommending that it may be prudent to hold off on new land purchases until after the Fed is done raising rates.

Higher interest rates may also hold a silver lining, Ehmke adds. “You may see outside investors less likely to put their money into farmland,” he says. “They’ll move to more viable investment opportunities like treasuries.

Jason Burbage, president of National Land Realty, says he’s seen some signs of this happening in recent farmland sales by his company.

“Outside investors are still there, but they are not dominating acquisitions,” he says. “The majority of Midwest land is still being bought by existing farmers with the ability to do it.”

Even so, keep in mind that outside investors will never completely vanish, Burbage says. That’s because land remains a very stable investment to make, especially over the long term.

“We’re not in an awful place,” he says. “It’s not as bad as we think. You still have to make smart decisions, but you don’t have to be driven by fear.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like