There is nothing quite like looking out a tiny window and seeing blue skies and white low-lying clouds, except perhaps the thrill of diving down to the tops of the corn tassel, pushing the button and watching the mist fly in your wake. The whole experience, both emotional and technical, is one Kiman Kingsley is fostering in the next generation of crop-dusters.

The Kingsley operation is diverse. Kingsley, who is a pilot, manages the ag aviation side of the business located on the family farm outside Miller, Mo. He is joined by brothers Kaland Kingsley, who is the chief pilot, and Kaleb Kingsley, who takes care of the farming end of the business.

Kiman Kingsley first sat in a plane’s cockpit more than 30 years ago after earning his private pilot’s license. “I got started flying pipeline patrol,” he says, “and did that for 10 years.” Then he returned to the family farm.

A fourth-generation grain farmer in Lawrence County raising corn, wheat and soybeans, Kingsley drove tractors. However, he longed to get off the ground and into the sky. “I love to fly, and I needed to figure out a way to have flying fit into my farming,” he says. For him, the solution was obvious. “It was crop-dusting.”

Ag aviation business grows

Kingsley traveled to South Dakota in 2005 and bought his first spray plane. “We did so well with it that summer that by September, we purchased a second one from Nebraska,” he says. And the brothers continued to add planes to their hangars, reaching 21 planes.

Today, the aerial application service of the family business known as Plane Cents Aviation services the Midwest — including Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Iowa and Indiana — mostly flying aerial applications on row crops such as wheat, soybeans and corn. However, Kingsley says the crew makes trips north to Montana for spraying sugarbeets. Another outlier crop are the pecan groves in Kansas.

The company sprays a wide array of products from fertilizer to herbicide and pest control. Kingsley admits spraying herbicides is tricky and often tries to avoid it, but when extremely wet conditions set in and farmers cannot get into their fields, “we will.” But wind speed always dictates application.

Over the years, he’s witnessed an increase in application of foliar fungicides in row crops. Kingsley’s crew also flies over a lot of pastures spraying for thistle. Still there is an emerging market for ag aviators: cover crops.

Kingsley says farmers are requesting aerial application of cover crops across more acres. “Here in Missouri,” he explains, “when the corn is tasseling, we will fly on forage turnips and ryegrass.”

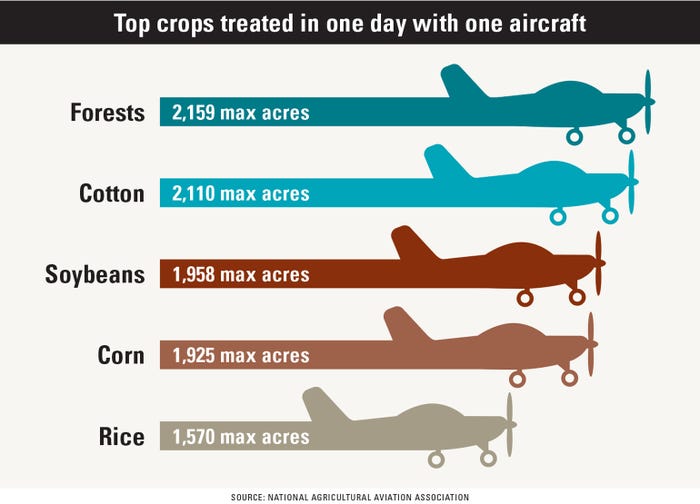

Whether chemicals or cover crops, the ag pilots are flying over a lot of farm fields. According to a 2019 National Agricultural Aviation Association study, the industry treats an estimated 127 million acres of cropland from the air annually, or about 28% of total crop production acres. To meet the growing demand for aerial application, Kingsley needs pilots.

Training next-gen pilots

There are more than 3,350 ag pilots in the U.S., which includes hired pilots. However, like the agriculture industry, the pilots are getting older.

Today, the average age of an ag pilot is 55 with at least 25 years of experience in the cockpit, according to the NAAA study. However, the study uncovered a promising trend — 25% of hired ag pilots were in the age range of 30 to 39.

With the shift toward younger pilots, there is a need for training specifically in agriculture applications. So, Kingsley developed a hands-on flight school on the farm.

The Ag Aviation School is located at Kingsley Field outside of Miller. There, Kingsley and his staff offer a unique experience for future crop-dusters.

The program trains young pilots by allowing them to learn and master the art of spraying on the family farm, which spans across 4,000 acres and two states — Missouri and Kansas. “We work here before we work for the customer,” Kingsley says. This year, he hosted his second student. Why so few students?

Crop-dusting is intense. It is not only flying under power lines and feet off the ground, but also understanding chemicals. Kingsley likes to keep the number of students low, offering that one-on-one instruction needed in such a niche industry.

Students must have their pilot’s license to enroll in the training program. “Those that come here typically have a family history of flying. Most have a flying background of their own,” he adds.

The 40-hour course teaches them how to fly an overloaded airplane under power lines. It is technical, teaching them how to set up a light bar to do three spray patterns — back-to-back, squeeze and racetrack. The last 10 hours, Kingsley works with the student to hone calibration. Since weather varies during the spray season, pilots need to adjust.

For example, one airplane can hold 130 gallons. On a morning spray that is nice and crisp and 50 degrees F, that may work, but when it warms up to 85 degrees in the afternoon, that amount is reduced to 120 gallons. Pilots need to know how to back the pressure down in order to do the same amount of work.

“You’re calibrating as you’re flying,” Kingsley explains. “You’re looking at the field, and you’re counting the passes over. If you see you’re running short or long, you either increase the pressure or back off. It’s just like a farmer whenever he’s spreading fertilizer. He cranks it up a little or back to make it come out in the field. There is a lot of technical and a little art to crop-spraying.”

At the Ag Aviation School, students receive a free private room in the pilot dorm and other amenities, such as internet and a washer and dryer. All of this is located above the family’s Hangar Kafe, an eatery on the farm built inside an old airplane hangar.

Future in flying

However, the cost to become an ag pilot is similar to a four-year college investment, topping $80,000. Students must obtain a private license, a commercial license and then ag training. “It takes an additional time in the cockpit of up to three years before they get to my school,” Kingsley says. “And then it is another three to four years spraying before they get good at it.” But Kingsley says there is a payoff.

An ag pilot can make up to $300 per hour, he notes. Taking the industry standard from NAAA of flying 150 days per year on average, putting in 10-hour days, it equates to $450,000.

Kingsley says this type of investment and payback is in an industry the next generation can count on for staying power, despite the addition of drone spray applicators.

“In wheat, when the flag leaf comes out, you’ve got 48 hours to get the chemical down and keep the head scab out and the rust down,” he says. “Airplanes move fast and cover a lot of ground. In farming, timing is everything, and ag pilots know that.”

And while Kingsley sees a place for drone applications, it is not across large acres seen in the Midwest. “Farmers keep flying on more cover crops. I don’t see that changing,” he says. “They need to grow crops in the winter. That’s going to require more airplane work.”

Kingsley enjoys sharing his passion for ag aviation. “It has provided a great life for someone who loves to fly and farm,” he adds. “It is about bringing along the next generation of ag pilots to meet the demands of the future of farming.”

For more details on the school and its offerings, visit Kingsley’s Ag Aviation School online.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like