A June 9 meeting between the Pennsylvania Farm Bureau and the Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 3 administrator seemed cordial enough, but it’s a sign that Pennsylvania agriculture is under the spotlight when it comes to the ongoing cleanup of the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

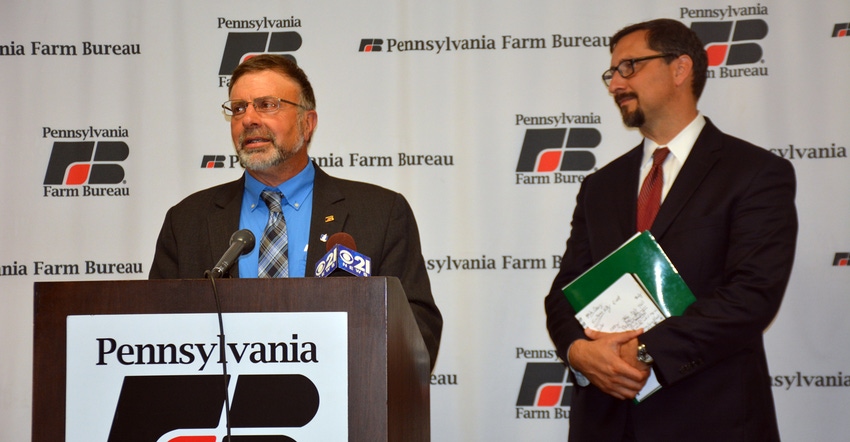

Rick Ebert, president of Pennsylvania Farm Bureau, and Adam Ortiz, administrator of EPA Region 3, talked for about an hour at Pennsylvania Farm Bureau headquarters in Camp Hill.

Here are some takeaways from the meeting:

Pennsylvania is under pressure. EPA set an overall pollution diet for the Chesapeake Bay in 2010. It set limits of 185.9 million pounds of nitrogen, 12.5 million pounds of phosphorus and 6.45 billion pounds of sediment per year into the bay, with the goal of having all practices in place to meet these limits by 2025.

Six states and the District of Columbia have local allocations based on their share of the overall total. Pennsylvania has the largest allocation of nitrogen — mostly from agriculture and mostly because of the Susquehanna River being the bay’s largest tributary — and the second-largest allocation of phosphorus and sediment.

But recent modeling, which EPA uses to keep track of nutrient reductions and is based on known best management practices on farms, showed the state further behind in its nutrient reduction efforts than previously thought, especially on nitrogen.

According to a recent article in the Bay Journal, annual nitrogen reductions from 2009 to 2020 were 6.25 million pounds less than what was calculated, largely because of new data showing the intensification of farms and a sharp increase in fertilizer use.

Modeling under fire. Still, the modeling the government uses has long been criticized for being inaccurate for not counting best management practices (BMPs) and other pollution reductions paid for out-of-pocket by farmers with no government help.

Ortiz defended the EPA’s modeling, but he acknowledged that live monitoring is the best way to know what reductions are being achieved and where.

"The decisions that are made for the Chesapeake Bay are done in partnership with the bay states and the District of Columbia, so we have to come to consensus on how we move ahead and whether we approve models or not," Ortiz said, adding that EPA is planning on meeting with state officials next month to talk about the model.

“Models are models,” Ortiz added. “We try to make them as scientific as possible, and tested and viewed by all stakeholders and partners. And then there's the data that goes into the model. So it's not going to be perfect, but it's a tool that we use. Monitoring is really important because that gets ground truths into the model, and without adequate monitoring, we rely a lot on the model.

"It's something [monitoring] that we've identified as member states and the federal government that we want to expand. Over time, we hope to rely less on the model and do more monitoring, but there's a learning phase.”

Ebert pointed to previous surveys done by Penn State and other partners that showed many BMPs — including cover crops, manure storages, riparian buffers and other practices paid for out of farmers’ pockets — were not accounted for.

Another survey went out earlier this year to farmers in 14 counties.

“I think the more we have these conservations, the better the model we'll have, and we'll have a better outcome for agriculture," Ebert said.

Enforcement actions underway. Nonetheless, Ortiz said enforcement actions, running the gamut from more inspections of farms under the government’s National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit program, and inspecting BMPs in problem watersheds, are underway in 10 locations.

Calling it a “state of Pennsylvania issue” and not a farmer issue, Ortiz said he has instructed inspectors to be fair and focus solely on areas with impaired waterways.

He said any BMPs found that are not accounted for in the bay’s model will be added.

Funding needed. The Farm Bureau’s relationship with EPA has been fraught at times, with the Farm Bureau filing a well-publicized lawsuit against EPA just after the total maximum daily load was implemented.

The lawsuit was eventually dismissed, and now the Farm Bureau is focused on getting more funding to farmers to get more pollution controls in place, and pushing EPA to better account for BMPs not paid for by government cost-share.

Ebert mentioned two bills under consideration in the Pennsylvania General Assembly — SB 465 and SB 832 — which would give more money for conservation funding for farms.

“Pennsylvania farmers have always been good stewards of the land,” Ebert says. “We’re doing all we can with the resources we have, but we need more assistance to achieve our common water-quality goals, especially in the current economic environment.”

Ortiz said the agency has pledged more than $250 million over the next five years to the Chesapeake Bay with some of that money going to Pennsylvania to get more practices in the ground.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like