Zac Erwin spent hours visiting with cattle producers at livestock sale barns in northern Missouri. They sat next to each other discussing nutrition plans, cattle prices and even family celebrations. That was only two months ago.

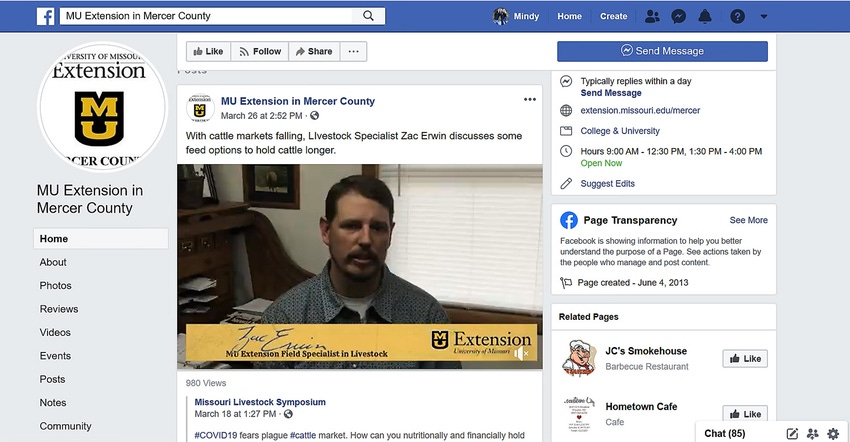

Behind a computer screen, Erwin (left) finds his new “normal.” The University of Missouri Extension livestock specialist is creating a video on how farmers can nutritionally and financially hold cattle weights during the current drop in market prices.

“It’s not like doing a video is reinventing the wheel by any means,” he says. “We are just trying to fill the void when we can’t meet with farmers, do a program or a seminar. We are still trying to get the information out there in a timely and responsible way.”

Communicating during crisis

Life in the agriculture world still moves forward. As essential workers during the coronavirus outbreak, farmers still are planting crops, feeding cattle and fertilizing pastures. So, Erwin is still on the job. He’s tapping into many communication platforms to reach his rural audience.

Facebook is the go-to for educational videos. In a world where information is at your fingertips, he says it is hard to keep videos at only 30 seconds. “The good thing on Facebook is it gives you feedback on how many people are watching,” Erwin says. He finds people are watching both long and short videos.

Oddly, the young professional just created a Twitter account. “It’s amazing who you interact with and the conversations you can have on it,” he notes. “You’re not just interacting with people a county away, but a state a way.”

Erwin still goes into the office located in Kirksville, Mo., a town of about 19,000 people. But it is eerily quiet as the Adair County MU Extension front door is locked, closed to visitors. “That has been one of the most surreal experiences,” he says. “We had a lot of foot traffic every day through that door; that has come to a complete standstill.” Still, the phones ring.

He answers calls from both the office phone and his personal cellphone, some calls more difficult than others. “I had a conversation with a guy holding 200 to 300 cattle who said if he sells at today’s prices, they are losing $100 to $200 per head. He can’t pay the bills,” Erwin says. “It is a tough conversation to have.”

In person, Erwin would’ve picked up on signals — how stressed did their face look, do the eyes say they want an answer or just to vent, or does the voice wane like they are tired or depressed.

“In person, you can react to those signals,” Erwin says. “I listen intently now. Sometimes, they feel better talking about it. Now, I’m a sounding board just listening, helping them walk through and talk through it, hopefully making it better at the end of the day whether we solve the problem or not.”

When his cellphone is not ringing, it is buzzing. “If they are age 60 and under, they text a lot,” Erwin says. And that is fine with him. He responds to every single text. “I just try to be available,” he adds. “That is what Extension is about.”

LUNCH CHAT: Sarah Havens (inset), MU Extension natural resource specialist, hosts a noon lunch meeting for women landowners through Zoom. People can view slides and visit via chat or video with others on the web-based application.

Virtual learning, sharing

For Sarah Havens, this new way of self-isolation offers unique challenges.

The MU Extension natural resources specialist opens Zoom on her web browser and starts to host a weekly lunch and learn called “Lady Landowner Lunches.” As individual names pop up on the screen, Havens welcomes them. They all can see her face and have the option to show theirs. It lasts about 25 minutes, then Havens opens the session up for questions and conversations.

Extension traditionally has supported women in agriculture. This program is part of Women Owning Woodland, a national initiative that provides education about land ownership, particularly around forest management.

Havens started prep work for the program months ago and was just about to launch the in-person meetings when the coronavirus pandemic hit. Small towns and even rural counties enacted stay-at-home orders. The University of Missouri shut down much of its campus and called on employees to work from home as much as possible. And there were to be no gatherings or meetings.

“I decided that women landowners would still be looking for these opportunities to ask questions and connect with other women, and that we could still do this on a virtual platform,” Havens explains.

And while Zoom is new to many people in rural areas and can be somewhat intimidating, Havens saw a lot of success with first-time users in the inaugural week. And it is offering her a greater reach. “We have people from all across the state tuning in,” she notes.

She found that this platform allows people to see and hear each other. “This seems especially relevant now in this time when we are all feeling a little isolated,” Havens says.

For many women, it is the first time logging on to Zoom, attending a virtual program or interacting with a chat feature. “My goal is to make it to where women feel comfortable asking questions, sharing goals and practicing technical skills in areas that have traditionally been a little intimidating,” she adds.

Out of her home office in south-central Missouri, Havens provides more than online education for women. She also offers a virtual program called Tree Talk Tuesdays. This is a series where any landowner can log in and learn practical information about their property.

For Extension specialists across Missouri or the nation, much of their time is spent on teaching, but in moments like these, Erwin says there is another aspect of the job that trumps even that focus.

“It is about personal relationships,” he says. “When you develop them over a decade, you know these people, their children, their grandchildren. You’ve eaten dinner with them. You know them like family. And when a family member is hurting or having problems, you need to be there. That is what Extension does.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like