December 4, 2017

By Curt Harler

David has won the latest round against Goliath in Erie County, Pa. It’s only one round, but a key round for farmer Robert Brace in a legal fight with the federal government stretching back 31 years to one of America’s first “swampbuster” cases.

The outcome could impact still more land. “My life ended 31 years ago,” Brace says. And he warns other farmers that their livelihoods are in danger, too.

The key legal points are: What constitutes normal farm practices in Erie County? And, what should happen if the federal government decides a farmer isn’t complying with regulations?

“They [U.S. EPA and Army Corp of Engineers] make the regulations. They interpret them,” Brace says. “You don’t have any rights at all.”

In September, Brace finally got a respite. The U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania ruled in favor of Robert Brace and Robert Brace Farms Inc. to deny the United States’ motions for protective orders. Those orders would have prevented Brace from digging into government records to help defend a long-standing battle over his farm’s Wetlands Restoration Plan and challenge a vague consent decree that surprised legal eyes that reviewed it.

Complicated by invading beavers

The issue dates back to when Brace’s father drained a farm more than 75 years ago. About the same time, beavers were introduced by Pennsylvania Game Commission into the area. Farmers had to remove the beaver dams to preserve their fields.

When Brace took over the farm in 1977, he fixed the drain field of the 30-acre plot Murphy Tract outside of Waterford, Pa. Then he planted corn instead of grazing it. By continuing to remove beaver dams to allow his fields to drain, the feds claimed Brace violated the Clean Water Act by damaging a “water of the United States.”

Brace argues the allegations were bogus due to a 1988 “prior converted cropland” exclusion granted to wetlands that converted to croplands before Dec. 23, 1985. His changes were made at least a decade before that. Since then, he has sunk a half-million dollars into legal fees defending his position.

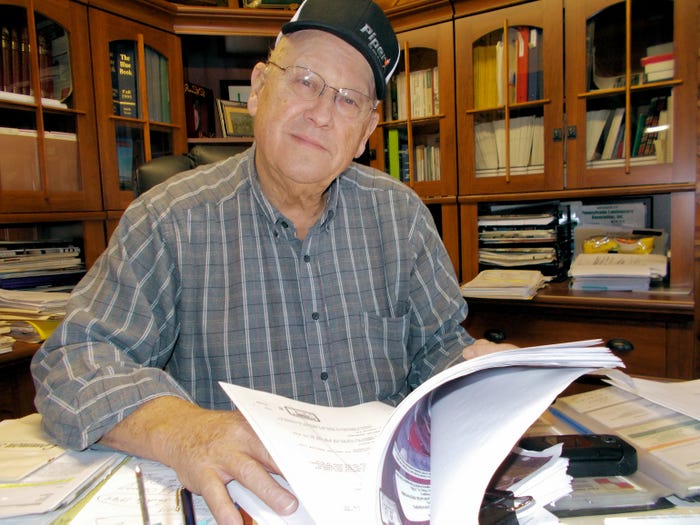

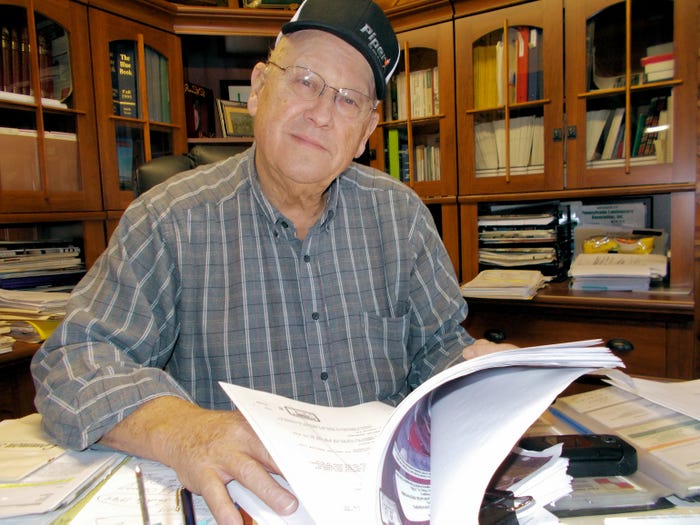

LEGALLY ‘BURIED’: Surrounded by tens of thousands of pages of legal papers, Brace reviews one sheaf several inches thick.

The Murphy Tract wasn’t well defined in the September 1996 consent decree agreement — another key component of the disagreement. It included a rough, hand-drawn map. A dirt road divides that tract from Brace’s Homestead and Marsh properties. One of the seven agencies with a say-so in wetlands noted the Murphy Tract wasn’t part of the defined area. Note: The Marsh property is named for the former owner, not as a wetland designation.

By 1996, the operation was Robert Brace & Son’s, Inc. Beavers built more dams. Waterflow patterns changed. Cropland — glacial land, some gravelly and some clay — was flooded.

Brace had contacted EPA several times hoping to get a definition of the boundaries of the area covered by the consent decree. Behind those calls was Brace’s need to move new beaver dams and clean ditches at various locations on his property to eliminate excess water accumulating on the farm’s uplands.

He had asked the Game Commission to remove the beavers or to let him remove them. This had been okayed several times in the 1970s and early 80s. But in 1986, the commission refused to allow it and threatened Brace if he removed the dams himself.

Back to the battle

To back his claim that nothing would change if he allowed the fields to drain, Brace wanted the feds to give him copies of pre-1996 federal and state agency aerial photography, satellite imagery, digital data, field logs, vegetation and hydrology data, wetland delineation reports, jurisdictional determination analyses and more. The feds said no.

Perhaps more controversial, Brace’s legal team wanted to be able to admit into evidence the pre-Jan. 14, 2005 federal court testimony provided by EPA’s star witness, Jeffrey Lapp. It directly related to the design, development and implementation of the 1996 consent decree. The government disagreed, contending the information Brace wanted was “not relevant.”

Brace’s legal team also wanted to depose a former Game Commission officer. Again, the government objected.

Winning a legal round

In September, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania sided with Brace. “Had these motions been granted, they would have effectively shut down Mr. Brace’s case,” insists his attorney, Lawrence Kogan of New York City-based Kogan Law Group. Kogan’s firm is working on the case with Neal Devin, an Erie attorney.

Brace possesses a USDA photo from 1983 (before the cutoff) showing the property with established, maintained drainage ditches and planted crops. He has an aerial photo showing the land was farmed as far back as 1939. A “swampbuster” letter from Erie County ASCS dated September 1988 noted: “The County Committee determined that conservation of wetlands began (on Brace’s property) before December 23, 1985.”

Once the Game Commission no longer allowed Brace to remove beaver dams, beaver ponds reclaimed his land. “Even if you’re legal at one point, [beavers] can recapture the property at any time,” Brace says.

Brace’s attorneys contended in their filing: “Genuine disputes as to the material facts of this case remain, which these discovery and testimonies would uncover.”

CULVERT CULPRIT: Township officials agree it should have been set two feet lower. As is, during high rainfall events, it backs 1.5 feet of water onto Brace’s land — making it a wetland.

Brace’s legal team argued that forcing EPA to turn over the requested documents and earlier testimony would give Brace’s legal team information to help resolve longstanding, unaddressed ambiguities — ambiguities leading to new charges that Brace Farms committed new violations between 2012 and 2015.

In court documents, the attorneys charged that the decree, restoration plan and hand-drawn map are “riddled with latent ambiguities since its execution by the parties and its entry into judgment by this Court, and the parties have failed to resolve these latent ambiguities ever since.”

Costly ambiguities

Here are key points of the Brace case, according to his legal team:

• The legal documents referred to “the site” when it wasn’t clearly defined.

• The restoration plan failed to distinguish the “hydrologic regime” of the Murphy 30 wetland acres from that of the remaining 28-acre upland portion of the 58-acre farm.

• The plan didn’t define the temporal period to which the hydrologic regime, and thus, physical condition, of the 30-acre wetlands is to be restored.

• No precise metes and bounds exist for the Murphy farm tract’s U-shaped wetlands adjacent to Elk Creek.

• The plan didn’t anticipate effects of natural and manmade phenomena within and beyond the Murphy Tract.

• Finally, EPA and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officials didn’t clearly define how to handle modifications.

Those “unresolved latent ambiguities” prevented the Braces from fully farming the remaining portions of their three contiguous, adjacent farm tracts totaling about 146 acres. At an average crop of 160 bushels an acre, that 30-acre plot might have produced 52,800 bushels of corn and generated more than $250,000 over the past 11 seasons.

Those many shortfalls, Kogan argues, kept them from remaining in compliance. The U.S. District Court resolved the issue: Brace may continue his discovery in the 30-year old case without interruption.

Next, Brace’s legal team expects to depose several witnesses. That should conclude by the end of January. Then, it’s back to court for another round.

Reopened wetlands case allows farmer to file $8-million claim against EPA tells more about why the court cleared the way for Brace’s legal defense. For another look at this situ, check out USA v. Robert Brace and Robert Brace Farms on YouTube.

Harler writes from Strongsville, Ohio.

You May Also Like