November 27, 2017

Editor’s note: This is the first story in a series exploring how ranchers and farmers are benefiting from renewable energy.

Wyoming’s a dang windy state, especially across the south and central portions where it’s not uncommon to see semitrailers on their sides.

Ranchers and farmers joke about the infamous Wyoming wind sock that’s built out of steel chains instead of nylon.

Some of these same ag producers, like many others across the Western Farmer-Stockman region, are profiting from these “gentle” breezes as the development of commercial wind farms continues.

Among those hoping to cash in are the owners of approximately 25 ranches and farms in southeast Wyoming, who formed the Slater Wind Energy Association nearly a decade ago.

In fact, they’re already profiting — though not a single turbine has been erected on their properties. These landowners are among a growing number in the region who have formed associations and signed long-term agreements with energy companies.

The associations can offer larger tracts of land; and in turn, there is the hope that “strength in numbers” will pay bigger dividends and offer more protections when it comes to property rights.

“Some of the landowners in our group have been a little disappointed that there hasn’t been any development, but we’re still hopeful,” says Gregor Goertz, Slater Wind Energy Association chairman.

OPTIMISTIC OUTLOOK: Southeast Wyoming agricultural producer Gregor Goertz is the chairman of a landowners’ wind association that is hoping all of its members will benefit if a wind farm is developed in their ranching and farming community.

“With recent conversations, I believe that Pathfinder will renew our contracts when they expire,” he adds. “We’re still optimistic that at some point they will build a wind farm, but that’s probably at least seven years out.”

Collecting land tracts

Since signing a contract with Pathfinder Renewable Wind Energy, landowners in the association have received annual per-acre payments for the lease.

“With a bigger block of land, we felt like we would be able to negotiate a lease — a much better lease since this is an area that was homesteaded in 320-acre parcels, and there are still many fragmented pieces of land,” Goertz says. “Because of that, it would have been much more difficult for a wind company to negotiate with landowners individually. It would take them a lot more time and effort.”

Goertz says that most of the local ranchers and farmers are excited about wind development, especially since the Niobrara oil play fizzled out in several counties that were expecting booms — including Platte and Goshen, two of Wyoming’s most important agricultural areas.

The Slater Wind Energy Association represents about 25 landowners on the Platte-Goshen county line. Since many of the landowners run cattle and raise wheat, they are hoping that some kind of diversification will help offset the major losses they’ve suffered with falling agricultural prices.

They each own from five to about 3,500 acres, but by pooling their lands they were able to offer a 30,000-acre tract to Pathfinder.

“It would be nice to have some additional revenue from wind development, especially since the oil didn’t come into play in our area,” says Goertz, whose family raises wheat, oats, millet and grass hay, and also direct-markets natural beef under the Wyoming Pure name.

But companies planning wind farms often face many obstacles, including finding buyers for their power, meeting environmental regulations and obtaining necessary permits to build infrastructure, including transmission lines.

“Getting the permitting for a major transmission line can be very difficult,” Goertz says.

He couldn’t get into the particulars of the contract between the landowners and Pathfinder, but noted that if a wind farm is built, landowners would receive royalty and per-acre payments with a minimum guarantee.

The Pathfinder project is already way behind schedule, as the company was hoping to begin construction on the massive 2,000-plus megawatt wind farm and associated transmission lines in 2016. As planned, the project would power some 2 million homes in the identified market of California, Nevada and Arizona.

Is a lack of wind resources playing into slow-moving Pathfinder?

Goertz starts laughing.

“There are a few days out here that aren’t windy, but that’s a real exception,” says Goertz, who occasionally finds himself chasing a hat across the windmill-dotted prairie. “They have three ‘met ’ towers on our association land, and they say the data has been very favorable.” (METs, short for meteorological evaluation towers, are used to measure wind characteristics and, ultimately, the suitability of a site for wind energy development.)

Goertz says that the contract between the Slater Wind Energy Association and Pathfinder expires in the coming months, and it’s his hope that all involved move forward together.

“I have visited with individual landowners in Wyoming and other states who have had wind farms built on their properties, and they all had very positive things to say about the development and the extra income,” Goertz says. “We’re hoping to see the same thing here.”

TOWERING TURBINES: This wind farm was developed on rangelands in southwest Wyoming near Evanston.

Helping everyone get a share of the pie

Approximately 25 landowners in southeast Wyoming, including ranchers and farmers, formed the Slater Wind Energy Association to negotiate with energy companies, in part because wind farms can impact many residents, not just those where actual development occurs.

“We’re doing a community model where everyone in the association gets a share of the revenue, not just those with turbines on their property,” says Gregor Goertz, association chairman. “We’re doing that because we believe everyone in the community will be impacted by a wind farm, regardless if it’s on their property or not.”

Goertz emphasizes: “We want to be good neighbors and take care of any protests prior to development.”

The Slater association formed nearly a decade ago and members are still hopeful (“cautiously hopeful”) that a wind farm will be developed in their area.

They joined forces during a particularly busy time for proposed wind energy development in the state.

In less than two years, the coordinator for the USDA Resource Conservation and Development office covering five southeast Wyoming counties helped dozens of ranchers, farmers and other landowners form 11 wind associations, including Slater.

That particular office has since been closed by the USDA amidst budget cuts, and the formation of wind associations has slowed down as well.

Speaking personally about his family, Goertz notes, “It’s our hope that a wind farm will be developed in our area, because that will help us and the next generation stay in business.”

U.S. landowners receiving $222 million annually from wind

There are many resources that farmers and ranchers can turn to when it comes to negotiating leases with potential wind energy developers.

Google such words as “wind farms landowner payments,” and you’ll find a host of material.

For example, there’s an article that encourages landowners to ask five questions before signing a wind-energy lease:

1. How will the lease affect my farming or ranching operation?

2. How long will the lease tie up my land?

3. What are my obligations under the lease?

4. How will I be compensated?

5. What happens when the project ends?

These questions and the associated elaboration come from National Wind Watch, a coalition of groups and individuals working to save rural places from “heedless industrial wind energy development.”

This is one of numerous groups that urge landowners to wave cautionary flags when it comes to wind development.

There are also groups that represent the interests of the country’s wind energy industry, including the American Wind Energy Association. AWEA says that companies are now paying $222 million a year to farmers, ranchers and other rural landowners who have wind energy development on their land.

It also says that landowners in six states receive more than $10 million a year in lease payments, with Texas ranked No. 1.

In the Western Farmer-Stockman region, landowners in Oregon, Washington and Colorado collectively receive $5 million to $10 million per state.

“The wind farm allowed us to be able to keep our family farm,” says Calhan, Colo., farmer Jason Wilson, on the AWEA website.

“We had come to a point where it no longer made financial sense to keep the property, even with its vast sentimental value,” he notes. “The wind farm balanced the financial viability with the sentimental value, allowing the family farm to continue to be passed on to the next generation.”

Landowners in Wyoming, Idaho and Montana collectively receive $1 million to $5 million per state, while those in Utah and Nevada receive less than $1 million per state.

Oregon, Washington and Colorado top producers in region

Texas is king when it comes to the largest installed capacity of wind energy in the country, accounting for 25% of the nation’s total.

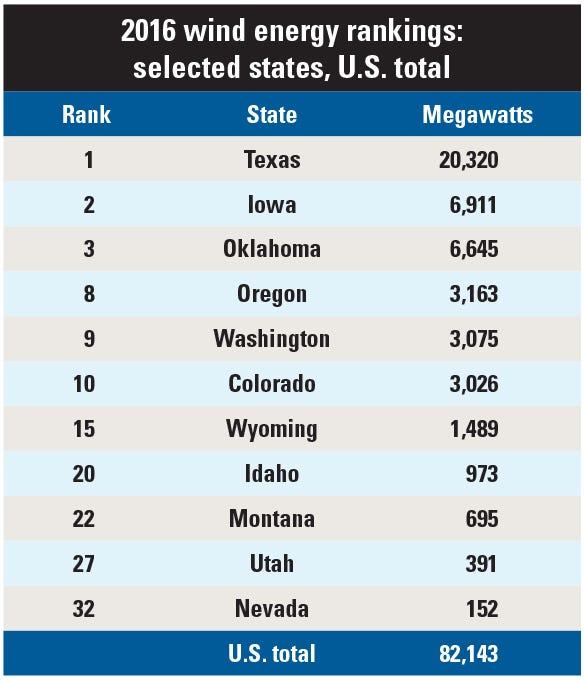

Iowa and Oklahoma come in a distant second and third, respectively, accounting for nearly 17% of the total, according to 2016 figures compiled by the Nebraska Energy Office.

But the eight states in the Western Farmer-Stockman region are collectively supplying a significant amount of the U.S. total as well (16%), and many agricultural producers in the region are financially benefiting because numerous wind farms are located on private ranch and farmlands.

As just one example, the Shepherds Flat Wind Farm, one of the largest land-based farms in the world (845 megawatts), is located on ranchlands in north-central Oregon, and the landowners receive annual royalty payments and other compensation.

Collectively, wind farms in the eight states in the Western Farmer-Stockman region produce 12,964 megawatts of electricity, enough to power some 10 million homes.

Oregon, Washington and Colorado rank eighth through 10th, respectively, with Wyoming coming in 15th.

Here are 2016 wind energy rankings for the top three states, eight states in the WFS region and the U.S. total.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like