Last month I introduced you to three post-harvest marketing friends: Barney Binless priced and delivered grain at harvest. May Sellers stored grain and sold it in late spring. Earl Eitheror made a choice. If carrying charges are large, he plays it safe by selling July futures (or a July HTA) against grain in storage. If carrying charges are small, he stores grain to price and deliver next spring, just like May.

Based on Iowa average prices, May and Earl beat Barney’s harvest price for corn and soybeans. May had the best average price but year-to-year swings could be great. For an example of a bad year for May, look no further than last year’s crop. It was her worst performance in 31 years – the economic fallout from COVID-19 was hard on producers holding grain in storage.

Earl’s average results lagged May by several cents, but he delivered more consistent positive results.

In baseball terms, you might think of May as a home run hitter with a tendency to strike out. Earl is a slap hitter with a great on-base average.

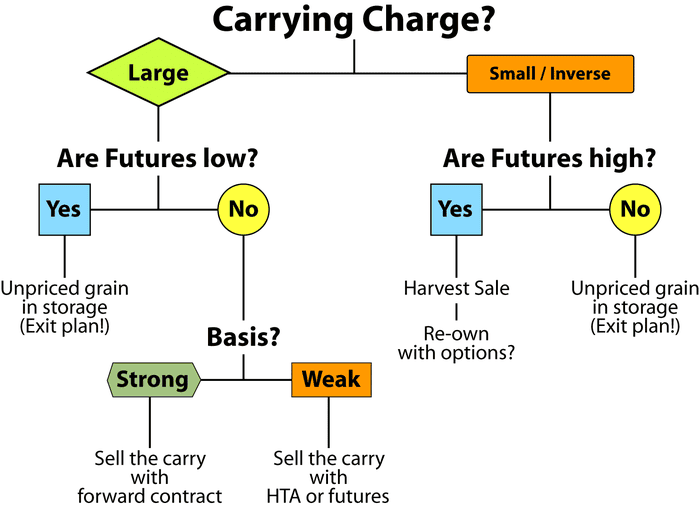

Carrying charges loom large in Earl’s post-harvest marketing decision. That is why carrying charges are at the top of my post-harvest marketing decision tree.

I encourage producers to use the decision tree to help them size up the market for post-harvest opportunities. Carrying charges – large or small – is where the process starts, but it is not the only question that must be considered. Here are a few more to consider.

Is basis strong or weak? Basis is a quick peek at local supply and demand conditions for grain. Your basis will tell you if the market needs your grain now or later.

Are market prices high or low? High and low are subjective terms. Suffice to say there is more downside risk in $4 corn than there is for $3 corn.

What are my storage costs? The key is to be realistic about your storage costs. If you depend on commercial storage and rates for storage, you will find it difficult to profit with any storage-based strategy over the long term.

What Is my appetite for risk? When market signals are mixed and your choices are unclear, your appetite for risk must play a role in your decision. It might help to remind yourself that you don’t need to be just Barney or May or Earl. Diversification is good!

Use the decision tree to help sort through your post-harvest marketing alternatives.

Is the carry large or small?

Avid traders track carrying charges as a percent of full carry in the futures market. My three-step approach is a modification intended for producers who want to measure the cost of carrying cash grain in storage.

Step 1: Calculate the carrying charge. This analysis can be applied to any commodity, and for any time frame for storage and the relevant carrying charge (e.g., Dec/Mar corn, Nov/May soybeans, Sep/Dec wheat, etc.).

3.55 (Dec’20 futures) - $3.75 (Jul’21 futures) = 0.20, or 20 cents per bushel

Step 2: Calculate a per bushel interest cost for grain held in storage. Assuming a farm is paying interest on an operating loan, storing grain costs money. Use your local cash price and interest rate. December to July is seven months, so I assume seven months of storage (months of storage must be adapted to the carry in question).

cash grain price * annual interest rate * months of storage / 12 months per year

$3.10 * 4% * 7/12 = $0.07, or 7 cents per bushel

This simple formula tells you that by choosing to hold corn in storage, you will incur interest costs of 7 cents per bushel.

Step 3: Compare the size of the carry to your interest costs. The last step is the easiest of all. Simply divide the carrying charge in question by the interest cost on grain held in storage

carrying charge / interest cost = carrying charge coverage of interest

20 cents / 7 cents = 285%

This relatively simple math exercise tells us that the current December/July carrying charge of 20 cents is nearly 3 times greater than interest costs. I define a large carry as a carrying charge greater than 140% of interest costs. This figure is large enough to cover all variable costs of storage (interest and shrink) and generate a benefit from selling the carry in the market.

Edward Usset is a Grain Market Economist at the University of Minnesota, and author of the book “Grain Marketing is Simple (it’s just not easy).” You can reach him at [email protected].

Read other articles in the Advanced Marketing Class series:

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like