Missouri farmers hammered by a deluge of rain last week may be facing nitrogen loss in cornfields.

Peter Scharf, University of Missouri Extension nutrient management specialist, found a field in Audrain County, Mo., showing a 46-bushel-per-acre yield loss because of nitrogen deficiency. He says farmers need to act quickly for nitrogen rescue applications.

“I think that we are poised to have a large problem with N loss,” Scharf says, “and there will not be a lot of time to respond.” He adds that farmers need to have a plan for how to assess N loss and to apply additional fertilizer if needed.

Too much precipitation

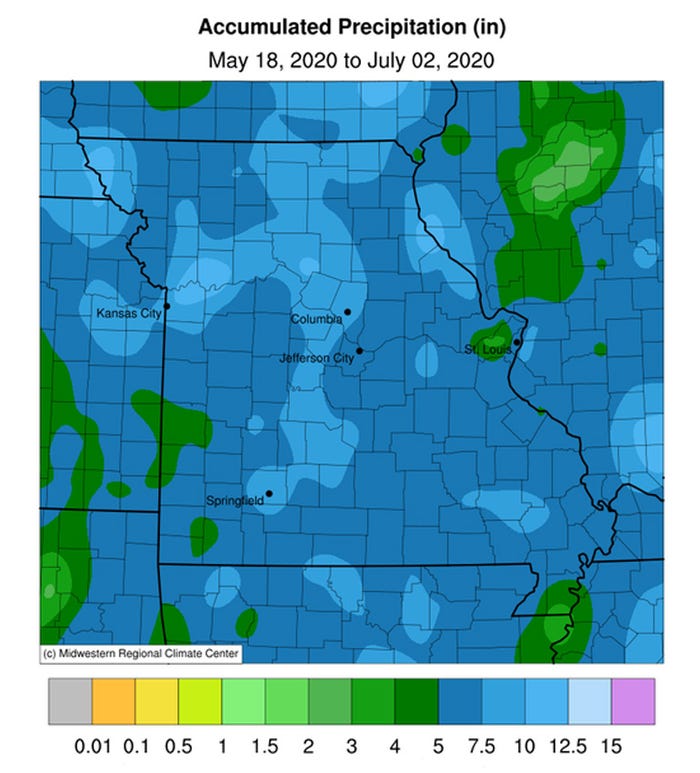

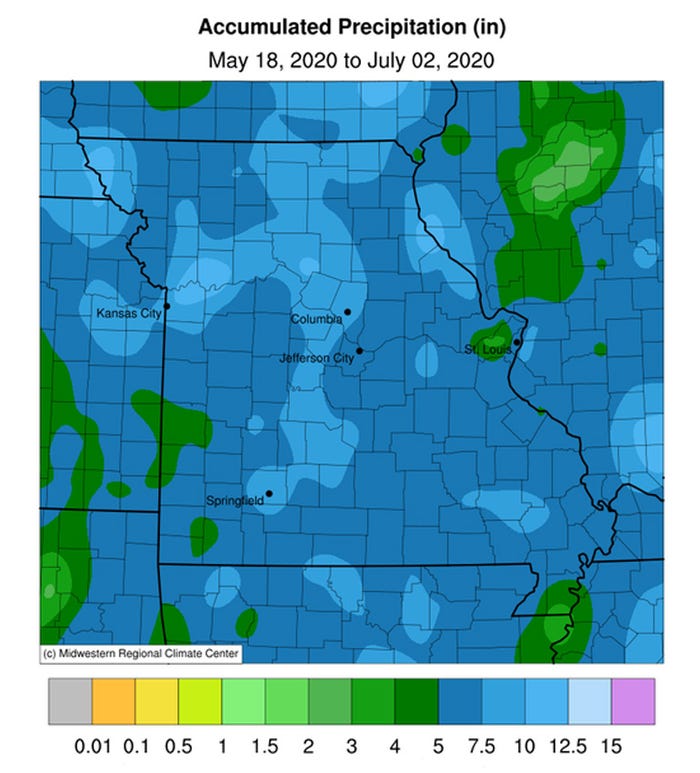

From May 18 through July 2, much of Missouri saw more than 7 inches of rain fall, with some areas receiving close to a foot of precipitation.

A precipitation map shows areas of Missouri receiving from 7.5 inches up to 12 inches of rain during this early part of the growing season, as of July 2.

This weather event places Missouri in the “danger zone” for nitrogen loss, according to MU’s Nitrogen Watch. The Nitrogen Watch website tracks spring rainfall and identifies areas that are on track to have nitrogen deficiencies.

The rain just added to an already wet season for some areas of the state. According to Scharf, farmers experienced some nitrogen loss when the tropical storm remnants swept up through the middle of Missouri in mid-June. “The late-planted, small corn plants will be the most likely to have nitrogen problems,” he says. Corn farmers should also look at poorly drained fields that stayed wet for several days.

How to spot nitrogen loss

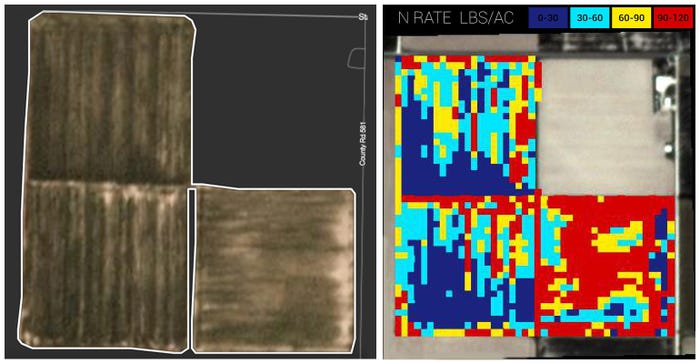

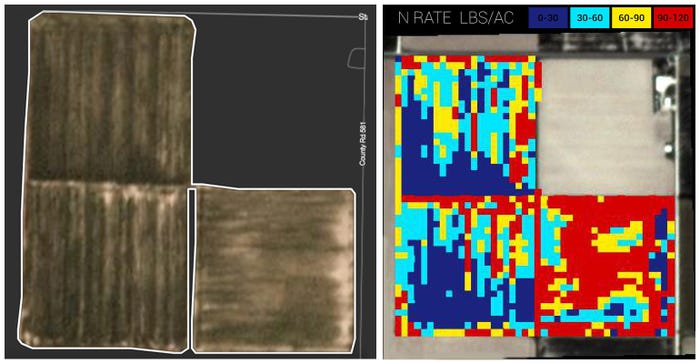

Aerial or satellite images allow farmers to view a lot of acres quickly, according to Scharf. But he warns that farmers should look for those companies or online tools that offer images in real color.

“Farmers have a gut feeling of what nitrogen loss looks like,” he says. “It is yellow or light green. But if they are seeing images with crayon red, yellow and blue, and no legend, the only way to see and truly know is if they go to the field where it is red and look.” That takes time. Scharf adds actual photos of fields are best.

One online offering just in time to determine nitrogen loss this season is from Planet Labs. This website is offering a two-week free trial. “This would work well for farmers who want to scan their fields for potential nitrogen deficiency,” he says. “Planet is getting an average of probably five images per week for every field in Missouri; so even if it’s cloudy most of the week, you have a good chance to get a good image when you want it.”

Scharf also has a company, NVision Ag, that interprets visual nitrogen loss from satellite and aerial images for farmers. The first interpretation is how many bushels and dollars will be lost if nothing is done, he explains. “That helps the farmer decide yes or no on buying more fertilizer and usually a custom application service,” he says. Then, NVision Ag tells the farmer how much nitrogen is needed at each point in the field — this is delivered as a computer file that controls the machine applying the fertilizer. “No point putting extra N on parts of the field where none was lost,” he says. “And N loss is always patchy; it happens much faster in the wet parts of the field.”

READING IMAGES: The image of an Audrain County, Mo., field (left) shows a satellite image of the true field colors, where yellow and light green show nitrogen loss. NVision Ag then generated the image on the right, which shows an anticipated yield loss of nearly 46 bushels per acre. The company also provides farmers with a rescue nitrogen prescription. (Courtesy of NVision Ag)

READING IMAGES: The image of an Audrain County, Mo., field (left) shows a satellite image of the true field colors, where yellow and light green show nitrogen loss. NVision Ag then generated the image on the right, which shows an anticipated yield loss of nearly 46 bushels per acre. The company also provides farmers with a rescue nitrogen prescription. (Courtesy of NVision Ag)

Another option to determine nitrogen loss is deep soil samples. Scharf says farmers should take samples at least 2 feet deep. “It requires lots of cores if N was banded,” he notes, “so they are hard work and slow.”

The MU Guide G9177 helps with interpreting the results. It can be used on corn up to hip-high.

For farmers signed up for nitrogen models like Corteva’s Encirca, Adapt-N or Climate FieldView Nitrogen Advisor, it is a quick tap to find and assess nitrogen loss. Farmers can sign up for these programs as well.

He adds that profitable yield responses to extra N on some fields, like those wetter than average or more vulnerable due to soils or management, are real.

In-season fertilizer application

Farmers can replenish lost nitrogen with in-season applications. John Lory, MU Extension nutrient management specialist, says these treatments protect a farmer’s bottom line.

“You can put nitrogen on remarkably late,” he says. “Late nitrogen, when needed, almost always pays and may not hurt yield as much as you think.” MU research shows that nitrogen application delayed until V12 to V16 rarely reduced yield potential.

Farmers should consider increasing nitrogen rates, and Lory adds that farmers have fertilizer options.

Urea can be broadcast over corn with minimal damage to the plants. Treat urea with a nitrogen stabilization product like Agrotain if applying to corn less than 2 feet tall, he says.

When using a urea-ammonium nitrate solution, farmers need to pay attention. Lory says to apply it below the canopy to prevent burning plant leaves. He adds using dribble or banded applications minimizes contact with surface residues that can tie up applied nitrogen.

Use of ammonium nitrate should only be done atop corn that is up to 2 feet tall. Any taller, and it can burn plants.

Line up fertilizer equipment

Access to equipment can be a limiting factor in late-season nitrogen applications. Scharf says farmers need to understand which machines can do the job, and at what cost.

In taller corn, large sprayers with Y-Drop work best for placing nitrogen close to the plant for. For shorter, late-planted corn, a high-clearance sprayer is best. “While planes work well,” Scharf says, “those will likely not be available, as many are switching to fungicide applications.”

If farmers want to hire someone to do their in-season nitrogen applications, reaching out now to the person who controls the machine is a good idea, Scharf says

While nitrogen loss this year is not expected to be that of 2015 or 2017, he adds a rescue application can decrease losses. “If you can take a field that was $10,000 yield short and make it $2,000,” Scharf says, “that helps the bottom line these days.”

There is a limited window for nitrogen rescue applications to actually pay off. Lory adds that in significantly nitrogen-deficient corn, rescue applications are likely to be profitable up to two weeks after silking.

The University of Missouri Extension contributed information to this article.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like