March 30, 2017

Editor’s note: This is the 13th story in a series exploring the opportunities and issues of potato growers across the region.

Chris Karren needed a new challenge, and he was also seeking ways to make his family’s farm more profitable and sustainable.

“I was looking for something that would not only challenge me, but would keep me busy year-round and ensure our farm’s long-term success,” Karren says. “We needed something to help us gain more control over our future.”

Karren’s family raises winter wheat, alfalfa, corn silage and sorghum-sudangrass on the Utah-Idaho border near Lewiston, Utah.

“We looked at getting into beef cattle as a way to diversify, and we even entertained the idea of a dairy,” Karren says.

Perhaps this is where a story of fate begins.

Opportunity knocks

It was early 2007 when Karren was visiting with farmer friends in Grace, Idaho, who grow seed potatoes. He learned about the risks they faced, but also the potential profits if they did things right. And doing things right meant embracing the day-to-day challenges that come with growing spuds.

His interest in potatoes was piqued.

At the same time, Potandon Produce (short for POTatoes AND ONions), a growing company, was looking for a reputable farmer to supply it with specialty seed potatoes. But the farmer needed to be in the right location: one that was centrally located to major commercial spud-growing regions, yet also far enough away from existing potato farms to reduce problems associated with disease.

Cache County, Utah, looked like an ideal spot, so company representatives began inquiring at places like farmer co-ops. “You need to talk with Chris Karren,” they would say. “He’s a reputable farmer looking to diversify.”

Within weeks, Karren and his family had inked a deal to give potatoes a try, and that year they produced an excellent crop of specialty potatoes that were sold commercially.

“Things worked out really well that year, and Dad and I thought it was a perfect opportunity,” Karren says. “Looking back, I think it was meant to be.”

But they knew the decision shouldn’t be taken lightly. That wouldn’t be fair for Potandon Produce, and a wrong move would not only hurt their reputation, but could also devastate their bank account— because getting into the seed potato business meant investing more than $2 million in storage facilities and equipment.

“Once you make the commitment, you gotta do it,” Karren says. “There is no way out.”

At the same time, Karren wanted to be sure that taking this major leap was truly the right thing to do, and after family meetings and some soul-searching, he signed a long-term contract with Potandon Produce.

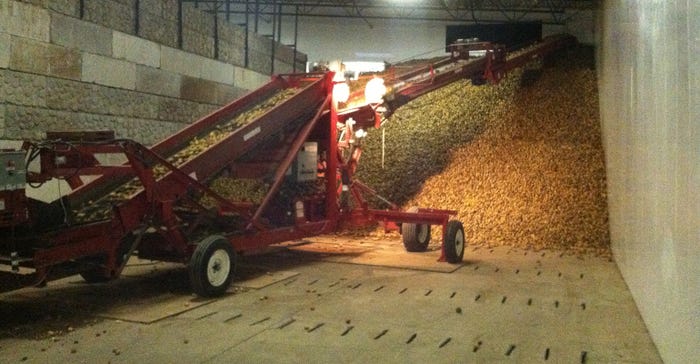

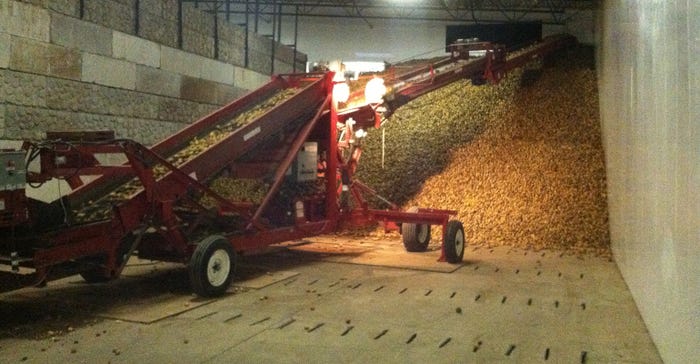

MONEY IN THE BANK: Seed potatoes are unloaded into a new, state-of-the-art storage facility on the Karren farm in northern Utah. Air flows through tunnels underneath the concrete floor and then rises through vents to provide uniform airflow. The exterior insulated walls, right, are lined with vinyl panels, which allow the facility to be thoroughly cleaned and sanitized between shipments.

Making the investment

The family pooled their financial resources with bank loans to purchase a planter, harvester and other equipment ($750,000 total). In 2008 the Karrens produced their first specialty seed potatoes, which were stored in rented facilities before being shipped to commercial growers around the country.

Then came an even bigger financial outlay — construction of a $1.5 million seed potato storage facility on their farm in 2009.

“Yes, it was a huge commitment. But it’s been very good. Seed potatoes have given us more stable income, a little more security — and they are allowing us to expand the farm and help the local economy,” Karren says. “Our farm is supporting more families than just ours. We now have five full-time employees.”

At the same time, he notes, they’ve developed an excellent relationship with Potandon Produce and, most recently, SunRain Varieties.

PAY DIRT: A foggy mid-September evening greets members of the Karren family and their employees as they harvest seed potatoes.

“They have been really awesome to worth with,” he says.

In 2014, Potandon formed SunRain, a subsidiary company based in Idaho Falls, Idaho, that markets specialty seed potatoes from coast to coast.

“All the seed potatoes I grow are for SunRain. It’s their seed to market and sell, so we work together very closely. They have as much interest and stake in this as we do,” he says.

Karren has also developed close ties with growers.

“They come here in the winter to inspect their seed and talk, and I make trips to their farms in summer to see how their crops are doing,” he says. “We talk back and forth to help determine if there are different things our farm can do to improve on something.”

Karren says he has found the challenge he was looking for, and also the sustainability.

“With some of our other crops, you might gain or lose $50 per acre, but with a seed potato crop you can gain or lose $500 an acre,” he says. “There is definitely a lot more risk, but if you work hard and do a good job, you can consistently be in the positive.”

Specialty spuds open up markets

Chris Karren believes there are growth opportunities for commercial spud growers across the region and country, especially when it comes to the growing demand for specialty potatoes.

“When people try these new varieties, they find out they are pretty darn good potatoes, and I believe there is definitely room out there for commercial growers to take advantage of this,” says Karren, who grows seed potatoes on the Utah-Idaho border for SunRain Varieties. “That could, in turn, allow the potato industry to better compete with other foods.”

Karren grows 20-plus specialty varieties for SunRain, including yellows, reds with yellow flesh, reds with white flesh, purples and fingerlings.

“Potatoes are a challenging crop, especially since we’re growing so many varieties,” he says. “You have to treat each variety a little bit differently, and we’re always tweaking things every year to improve and try and make things better.”

Karren uses seed from SunRain’s farm in Driggs, Idaho, and from farms in Canada that grow younger generations of potatoes.

“We don’t grow our own seed because SunRain likes to move from farm to farm each year. They don’t want their seed planted back to back in fields, to help keep disease problems from developing.”

Karren is equally diligent about disease control in the seed potatoes that he, in turn, produces for SunRain’s customers.

“Our goal is to only plant potatoes in a field once every five years. Potatoes are typically followed by winter wheat, and after the fall harvest we plant a cover crop to put nutrients and organic matter into the field,” Karren says. “That next spring we’ll plant corn silage, and we’re moving in the direction of planting directly into cover crops.”

Corn is typically followed with winter wheat and then another cover crop (such as radish or sunn hemp). The following spring the field will go into sorghum-sudangrass. The Karrens also grow alfalfa.

These crops are sold to local dairy farms. In turn, the family receives composted manure from the dairies, in addition to composted chicken manure from a nearby commercial egg farm.

“We still use commercial fertilizers based on soil testing, but the compost and cover crops have definitely helped our fields. They give us very good bang for our buck.”

Chris Karren and his wife, Karen, own 700 acres, while his parents, Keith and Kathy, own 300 acres. In addition, they rent 1,900 acres.

They typically have 1,000 acres in winter wheat, 500 acres in corn silage, 500 acres in alfalfa hay, 500 acres in seed potatoes and 400 acres in cover crops, including sorghum-sudangrass, radish and sunn hemp.

Chris Karren says they grow about 15 million to 20 million pounds of seed potatoes annually, and these are certified disease-free through the Idaho Crop Improvement Association. Most of their potatoes are trucked to Idaho, but they also send shipments to Arizona, California, Colorado, Washington and Canada.

“We would like to expand our seed potato acreage by 500 to 600 acres and try to specialize in fewer varieties, but that will depend on SunRain’s needs,” Karren says. “It is difficult to grow so many varieties, but I do like challenges. It will take me many years to get bored growing potatoes.”

Diseases a top issue facing potato industry

What is the biggest challenge facing the U.S. potato industry?

“From my perspective, the biggest challenge is definitely all the diseases out there,” says Chris Karren, a fifth-generation Utah farmer who started raising seed potatoes a decade ago to diversify the family business and pave the way for the next generation.

“Every potato producer — both commercial and seed growers — needs to be on the same page in trying to address this issue,” Karren says. “If your neighbor is lazy and doesn’t do what he is supposed to be doing, you’re going to end up with the same problems.”

Karren attributes part of the disease issue to farmers letting their guard down when it comes to everything from the seeds they plant; to soil, irrigation and crop management; to harvesting and storage.

“Some growers have gotten a little slack, and that is one of the reasons why we’ve run into the mess we have when it comes to zebra chip, late and early blight, PVY [potato virus Y] and blackleg,” Karren says. “I think that rotations are often too quick, that fields aren’t ready for potatoes yet.”

Karren admits to being a newcomer to potato production, and though he has tried to learn everything he can from a wide variety of sources, the school of hard knocks has still come knocking.

“One year we had a very wet spring and had to deal with some late blight. Sometimes things just happen that you can’t control, and weather is one of them,” he says.

“We’re always trying something new, doing experiments, trying new products, seeing if we can do better than the year before. But sometimes Mother Nature ruins something for you. That can be devastating, but you just try to accept the fact that things happen.”

Karren says he tries to stack the deck in his favor.

He is diligent about planting seeds in clean fields to keep disease down, and four years ago started planting whole seed instead of cut potatoes. This meant another capital outlay, as his family purchased a Grimme belt planter.

“Planting whole seed versus pieces keeps the seed a lot healthier, and it has also made a noticeable difference in our production, he says. “We’re getting higher yields and more uniform sizing.”

Storage has been another key component.

The Karrens still rent storage facilities in Idaho, but in 2009 built what Karren calls a state-of-the-art storage facility on their farm. It’s constructed of reinforced 8-inch-thick concrete walls poured between 2-inch-thick panels of insulating polystyrene. Air flows through tunnels underneath the concrete floor and then rises through vents to provide uniform air distribution to the seed potatoes. The interior of the facility stays a consistent 38 degrees F throughout winter.

The interior walls were lined with tongue-and-grove vinyl panels, which allow the two bays to be thoroughly sanitized between shipments.

“We’re looking to build another storage unit,” he says. “We’re looking toward the future.”

Waggener writes from Laramie, Wyo.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like