How difficult was the 2019 planting season in many areas? Planting was delayed for weeks; then in some spots, particularly the eastern Corn Belt, it began raining June 15 and rained 10 days straight, dumping 6 or more inches in places. The season went from bad to one of the worst early starts to a growing season ever.

“Many had no choice but to plant into conditions that were less than ideal,” says Gary Steinhardt, Purdue University Extension agronomist and soil scientist. Steinhardt was one of the agronomists who first brought soil compaction to light in the early 1980s, when farmers began complaining about “tall corn-short corn” syndrome.

Soil management payoff

“Soil compaction was a cost of doing business this year,” Steinhardt says. “What you can do now is identify it, understand possible long-term impacts and develop plans to address it. There are no easy answers and definitely no silver bullets.”

He adds this observation, however. “I’ve noticed that in well-managed fields with good soil structure before soil compaction occurs, recovery occurs more quickly,” he says. “Those soils seem to be more resilient. There will still be an impact, but it usually isn’t as severe and may not last as long. Look at it as a reward for doing things right.”

This phenomenon was evident when Steinhardt inspected fields along a stretch where a pipeline had been installed in Illinois a few years ago.

“Looking at disturbed areas and areas that weren’t impacted by the pipeline, it was clear that where soil structure was better and where fields were managed properly before the pipeline came through, recovery was faster,” he explains.

The first step in addressing soil compaction is finding it. Perhaps it’s just on the surface. Maybe it’s sidewall compaction. Or perhaps it’s much deeper.

“Dig a small pit with a shovel in a spot where you suspect compaction,” Steinhardt says. “Find layers and identify how deep they are in the soil.”

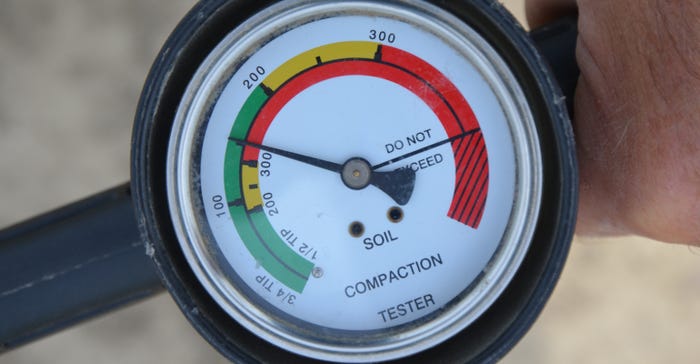

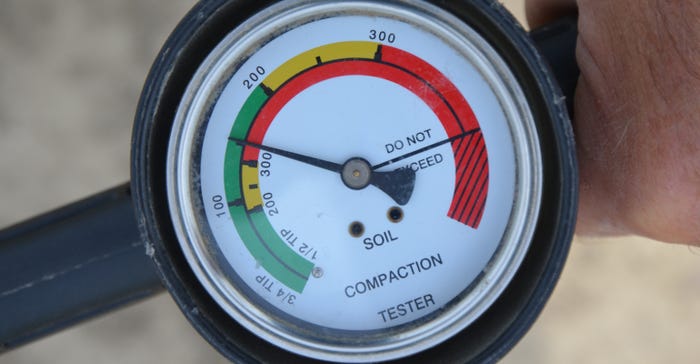

Then you can check the rest of the field with a tile probe or penetrometer, he adds.

“These tools are faster once you know what you’re dealing with,” he says. “If soil type varies, patterns of soil compaction may vary.”

A penetrometer is useful, but don’t get hung up on numbers or colors, he adds.

“Those readings are relative, not absolute,” Steinhardt says. “They have value making comparisons in the same field or same soil type, but aren’t helpful making comparisons between different fields.”

FIND COMPACTION: A soil penetrometer or tile probe can help you find compacted layers. Don’t get hung up on colors or numbers, Gary Steinhardt says — just use it to identify compaction.

Possible remedies

When it comes to strategies for dealing with soil compaction, some people suggest deep tillage.

“Tilling deep, but not too deep, may have merit in some cases, but we’ve never been able to prove it in research plots,” Steinhardt says. “Still, if you have identified layers 8 or 10 inches deep, it may be worth a try in those areas — not necessarily across the whole field. Deep tillage is expensive.”

Some advise letting Mother Nature take care of compaction with freeze-thaw cycles. Depending on where you’re located, that value is often overrated, Steinhardt says.

“Lafayette, Ind., happens to be at the right latitude to get the maximum number of freeze-and-thaw cycles,” he says. “If you go farther north, the number of cycles decreases because the soil stays frozen. If you go south, it doesn’t freeze as much.

“The other consideration is how deep layers are located. Freeze-thaw cycles can perhaps help on surface compaction, but it will take much longer if compaction is several inches deep.”

What you do in 2020 may depend on the weather next year, he adds. “If it works out, soybeans would be a better choice in fields with severe soil compaction,” he adds. “They may look ragged, but at harvesttime it’s often hard to pick up a yield hit.

“A yield hit is more likely on corn the next year. But if it’s a good season with moisture at the right times, yields may be good. I’ve seen that happen in plots compacted on purpose. Then for the next two years with less-than-perfect weather, there were yield hits.”

Cover crops

One new arrow in the quiver is cover crops, Steinhardt says. “Consider seeding a deep-rooted cover crop this fall,” he suggests. “Soil compaction may affect them, but they’re more likely to move through it. Many of them are known for good root penetration.”

Some people believe alfalfa can fix compaction problems. “It’s not as effective in the short term as you might think,” Steinhardt says. “Alfalfa can be affected by soil compaction too. In the long term in rotation, it helps. That’s why we didn’t see ‘tall corn-short corn’ until after several years in rotations without crops like alfalfa and wheat.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like