December 11, 2020

Seed catalogs and flyers are likely arriving at your doorstep right now.

One change many farmers are making is shortening the season of their corn silage. With the large swings in weather patterns, a sure crop that reaches optimum maturity is a more cautious approach to ensure forage production.

Variety trials over the past decade have shown corn breeders’ efforts have produced higher yields from traditionally shorter varieties. Longer-season varieties don’t guarantee higher yields.

Before you wax hysterical that we must grow the longest-season corn to get maximum yield, consider these two points:

First, based on Cornell test plots, there is only a slight but consistent yield increase from longer-season corn. There also is an increased risk of the crop not maturing or having to harvest in late-season mud, compacting the soil for long-term yield loss.

The other benefit of the shorter-season type is that it allows double cropping with winter forage, which takes more advantage of a full growing season than do long-season varieties. This can directly increase your yield per acre by as much as 30% to 35% per year while simultaneously conserving soil and nutrients, and improving soil structure for the long term.

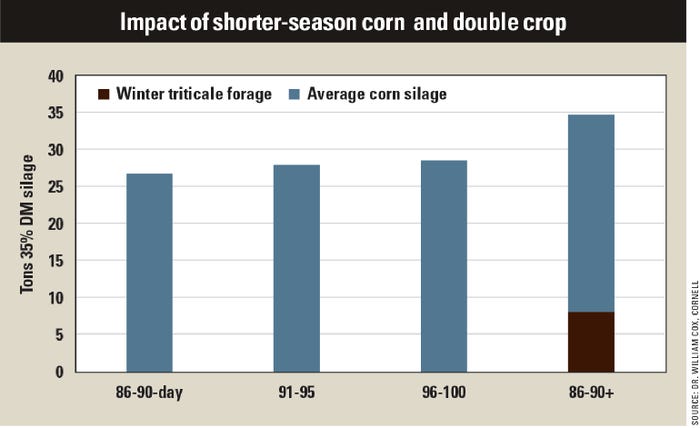

As you can see in the graph above, when we shorten the corn season, on average you lose three-quarters of a ton of silage for every five days shorter. Differences between varieties of the same maturity can be greater than that.

Shortening the season from 95- to 100-day down to an 85-day variety would theoretically lose 3 tons of silage per acre or 1 ton of dry matter. If we get the mature corn silage harvested before Sept. 10 in the Albany, N.Y., area, winter triticale can be in the ground on time and yield 3-plus tons of dry matter, or gain more than 8 tons of silage to replace what was lost from the shorter corn silage season.

The slight decrease in corn yield is more than offset by a threefold increase in total yield of winter forage that is far superior to support high milk yields than the corn silage you’re giving up. Slightly shorter-season corn will allow you to maximize winter forage potential.

Learning by doing, Part 1

We had a great setup. If a hay stand is lost over winter, we would simply no-till oats very early in the spring to take advantage of the nitrogen and the cool spring temperatures to capture as much of the season as possible.

By mid-June, when the oats are at flag leaf stage, we would harvest it as silage and then immediately no-till BMR sorghum or sorghum-sudan as a second forage crop to be harvested in early September.

We tried this system this year. The oats went in very early with enough nitrogen to fully grow. After it was harvested, the entire area — both the where the oats were and the control blocks with weeds between them — was treated with glyphosate. BMR sorghum-sudan was then planted across both the oat blocks and the fallow control between them.

The result: a complete disaster.

Apparently, the oat residue has a very negative effect on the sorghum species that follows. It wasn’t a moisture issue, as we had enough rains, and the control block had weeds that removed moisture. It was not nitrogen as all the blocks were fertilized.

Unfortunately, the sorghum only grew where there had been no forage oats this spring. Until we sort this out and double-check our results, I suggest that you don’t follow oats with a sorghum species.

Learning by doing, Part 2

We know from farmer experience that we can grow excellent framed heifers at lower cost without getting them fat by using a non-BMR sorghum or sorghum-sudan. We would like a little more protein in the mix.

To achieve this end, we planted sorghum-sudan and cowpeas (a summer pea). The idea was that the peas would climb on the sorghum plants to get their share of sunshine. We planted both in the beginning of June.

Unfortunately, either the peas grew too slow or the sorghum grew too fast. At the end of the season, we did not have much biomass to justify the pea seed expense. Based on these results, we suggest that you simply use a good non-BMR sorghum or sorghum-sudan fertilized with nitrogen and sulfur to support a higher-protein forage.

Why share my mistakes?

I pass this information onto you so you know what not to do, which is as important as knowing what to do. My job is to make the mistakes so you don’t have to. My farmer friends have converted that last sentence to “we knew you were a professional screwup!”

Nevertheless, it’s great to have friends!

Kilcer is a certified crop adviser in Kinderhook, N.Y.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like