When you think of soybeans, western Nebraska likely is not one of the first places that comes to mind. It's higher elevation and drier climate make it a harsh environment for any crop.

However, it's not uncommon for some irrigated corn growers in southwest Nebraska to plant soybeans as a rotation crop with corn. According to USDA Farm Service Agency planted acreage data, southwest Nebraska farmers on average plant irrigated soybeans every fifth year.

Still, even those that plant soybeans don't always give it priority when planting time comes. Strahinja Stepanovic, Nebraska Extension educator in Perkins County, notes that when it's crunch time, it's worth considering planting soybeans first.

In 2018, Stepanovic evaluated the effect of several factors when planting soybeans in western Nebraska as part of a study on two fields in Perkins County — this included planting date, row spacing and seeding rate.

Of those factors, planting date is the one that provides the biggest opportunity for profit, Stepanovic says.

"Some research in Iowa says you can retain 99% of the yield potential by planting corn before May 20,” he says. “Some of our dryland corn research on planting dates says we're losing half a bushel to a bushel per day in corn. With soybeans, we're losing anywhere from 0.64 to 1.4 bushels per day. With corn prices lower than soybeans, that's a big difference in economic loss. You typically have fewer soybean acres and don't have to plant as many, so you might as well finish soybeans first."

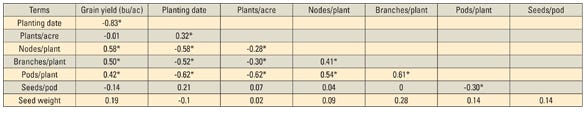

YIELD FACTORS: Correlation between soybean grain yield, planting date, plants per acre (at harvest), branches per plant, nodes per plant, pods per plant, seeds per pod and seed weight (1,000 seeds) in field experiments in Perkins County in 2018. * Indicates correlation coefficient significant at 5% level. The sign of coefficient indicates the nature of relationship (either positive or negative), while the magnitude of coefficient (ranging from 0 to 1) represents the strength of the linear relationship. Source: UNL CropWatch.

And, planting early also made the biggest difference in yield. In this study, planting in early May compared with early June significantly improved soybean yields — by 20 to 40 bushels. Stepanovic notes that planting only 10 days earlier can mean an additional $48 to $112 per acre.

In eastern Nebraska, soybean growers gradually have cut seeding rates down to about 90,000 to 120,000 seeds per acre. In western Nebraska, it's a different story. There hasn't been as much on-farm research dedicated to soybean planting populations, and populations typically average about 145,000 to 170,000 seeds per acre, although some plant as high as 200,000 seeds per acre.

"The reason is we get hail injury and then a stand reduction,” Stepanovic says. “We are in an area with a high incidence of hail. Sometimes soybean fields get hailed on and are left with 80,000 plants per acre. Most farmers would replant at that point. So, it's not only a matter of what you plant, but when you get hail, how do you make a decision to replant? Oftentimes growers replant and have the additional cost of buying more seed and planting. That's where they lose more money."

Stepanovic evaluated two populations: 90,000 and 140,000 live seeds per acre. At both farms, increasing populations had no effect on yield — even in fields with a lower final stand count because of hail. Reducing populations also cut seed costs by $15 to $20 per acre.

"One of our one-farm studies had some 75-bushel yields with [a final stand of] 70,000 plants per acre," Stepanovic says.

What did result in a yield increase, he says, was narrow row spacing. Based on several on-farm studies in the area, going from 30- to 15-inch rows consistently resulted in a yield increase of anywhere from 3 to 13 bushels per acre. With only a 3-bushel increase, narrow rows resulted in a profit of about $24 per acre.

"Soybeans like to branch out more when they're in narrower rows,” Stepanovic says. “If they're in 30-inch rows, there's a lot of space to branch out, but for some reason they don’t do that. Soybeans seem to like branching in every direction, so when we reduced inter-row competition between soybean plants, by going to narrower rows but keeping the same population, soybeans branched out more, and those branches added more pods on a plant. I was amazed by how many more branches we had with 15-inch rows. It was very consistent. With 30-inch rows, seeds are 1 inch apart. With 15-inch rows, it's the same seeding rate, but seeds are 2 inches apart."

Planting in 15-inch rows also resulted in more pods per plant — in some cases, it made a difference of about 15 or more pods per plant.

"Among these factors, early planting is the one that's most often overlooked, and it has the biggest opportunity to gain in profit," Stepanovic says. "Seeding rate and row spacing also make a big difference. Until now, there hasn't been much research on soybean planting in western Nebraska. With these numbers, we're hoping to encourage growers to think about ways they can improve overall profitability on their soybean acres."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like