December 20, 2016

“I think it is extremely interesting that the county that I live in, Washington County, is identified as a 'food desert,' but I never knew it,” says farmer Jared Baird.

Baird isn’t alone in this sentiment. While food deserts are most commonly thought of as urban areas, rural food deserts exist, too. But what exactly is a food desert? Moreover, exactly how many people are affected by food deserts? USDA can provide some insight to answer these questions.

Food deserts are communities that have low access to healthy and fresh foods, such as fruits and vegetables. USDA defines a food desert as a low-access community. Low-access means at least 500 people and/or at least 33% of the census tract's population must reside more than 1 mile from a supermarket.

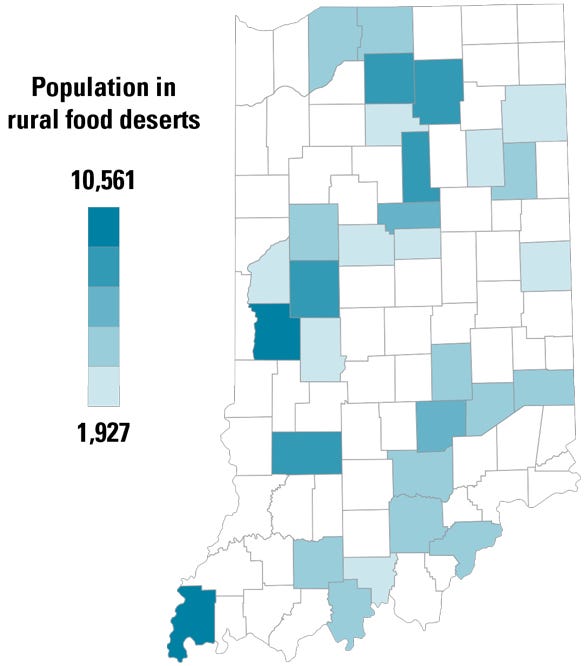

Rural areas are considered a food desert if 33% of the people are more than 10 miles from a grocery store. According to USDA, almost 23.5 million people live in food deserts.

Big opportunity

In Baird’s stomping grounds of Washington County, USDA reports that out of a tract of 4,700 people, nearly 4,655 are half a mile from a grocery story. At 1 mile away in the same tract, nearly 4,466 people are classified as low-access, and at 10 miles in the same tract, nearly 1,000 people are classified as low-access to quality foods.

“I didn’t think that we lacked for fresh fruits and vegetables in this area,” Baird says. “I guess that as a farmer, I should know more about my local demographics to understand that there might be more opportunities here that could provide another sales venue for our products.”

Baird’s farm is a prime example of how some food desert areas can improve access to healthy foods. Baird’s family farm, Cornucopia Farm, raises strawberries, tomatoes, sweet corn, and a variety of pumpkins and squash. The Scottsburg farm sells the produce on-site and a local farmers markets. Farms like Baird’s can continue to use niche markets, on-site sales and roadside stands to improve access to healthy foods.

Food desert hits home

There are often serious health implications when communities like Baird’s lack fresh fruits and vegetables. In fact, a study published by the American Journal of Public Health reports that census tract-level food deserts were positively associated with people being classified as either obese or overweight.

A census tract-level switch from a non-food desert to a food desert increased an individual’s chances of being obese by about 30%. The same switch also increased the odds of being overweight by about 19%.

“Sometimes just creating new markets and more access to food isn’t the solution. Some people in food deserts don’t even know how to properly prepare fresh foods or cook with them,” says Baird.

Given the correlation between food deserts and poor health, Baird and others feel that implementing education and programming to improve the overall quality of well-being in food deserts is a step in the right direction. New markets alone will not solve the problem.

Community solutions

Garden on the Go is a program offered by Indiana University Health to address the issue of food deserts. The program is working to improve access to fresh, healthy foods. Purdue University Extension specialists in Marion County joined forces with the IU Health team and hosted demonstrations on healthy cooking that used the fresh foods provided by Garden on the Go. Extension specialists taught those in attendance how to prepare the fresh fruits and vegetables.

In one demonstration, attendees learned how to use fresh peppers and cilantro in a hearty salsa dip. This joint program has provided two different solutions to food deserts by not only improving access to healthy foods, but also teaching people how to prepare and use the healthy foods.

In addition to the joint Garden on the Go program, Purdue Extension has other efforts to educate residents in Indiana about food deserts. According to specialists, the Purdue Extension Nutrition Education Program works to improve the nutrition and health of audiences with limited resources. Community wellness coordinators work within Purdue Extension’s Nutrition Education Program to help make the healthy choice the easy choice. Community wellness coordinators encourage people to choose fresh fruits and vegetables as snacks over less healthy options, such as potato chips or candy.

According to the Nutrition Education Program’s annual report in 2015, Purdue Extension hired 31 community wellness coordinators. Currently, 69 of the 92 counties in Indiana have at least one coordinator working to improve nutrition and health in their communities.

Offer help

Jered Blanchard, a community wellness coordinator in Allen County, says he focuses on community development and partnerships by speaking at town hall meetings, community foundations and health coalitions on the importance of creating better access to healthy foods.

Blanchard has given presentations on food access, obesity and health trends at several town hall meetings in order to further education people on the topic of food deserts. In his involvement with the health coalition and community foundation in Allen County, Blanchard has worked to encourage funding allocation for food desert areas. Education and outreach efforts like these are assisting with increasing awareness and providing solutions to the complicated problem of food deserts.

Farmers markets are another effort that Blanchard says can be used in fighting food deserts. In Allen County, there are 10 farmers markets where people can purchase fresh produce. Blanchard says the problem is that not many of the markets accept Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or Women, Infants and Children. Blanchard and Purdue Extension have worked on educating vendors at the markets on how to become SNAP- and WIC-approved.

While realizing new markets and improving education are two ways to help reduce food deserts, both farmers and Extension specialists realize there is a long way to go in solving the problem and eliminating food deserts. It will take a variety of new ideas and collaboration to successfully quench the thirst of those who live in food deserts, specialists say.

“I do not believe that the farmer is going to be the only one to solve the problem of food deserts,” Baird says. “The person who solves the problem of food deserts is going to be someone who lives right in the middle of the food desert itself, and who takes it upon themselves to make a change to the system and the way they access food.”

Mann is a senior in ag communication at Purdue University.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like