Nathan Crooke scored the all-time highest yield last year in the Pennsylvania Soybean Yield Contest.

But he doesn’t anticipate breaking records this year. Mother Nature isn’t cooperating.

“It’s just been so dry. I don’t think the beans are going to fill out enough unless some late rain saves us,” says Crooke, owner of Windybush Hay Farms, an 1,800-acre operation in Bucks County, just north of Philadelphia.

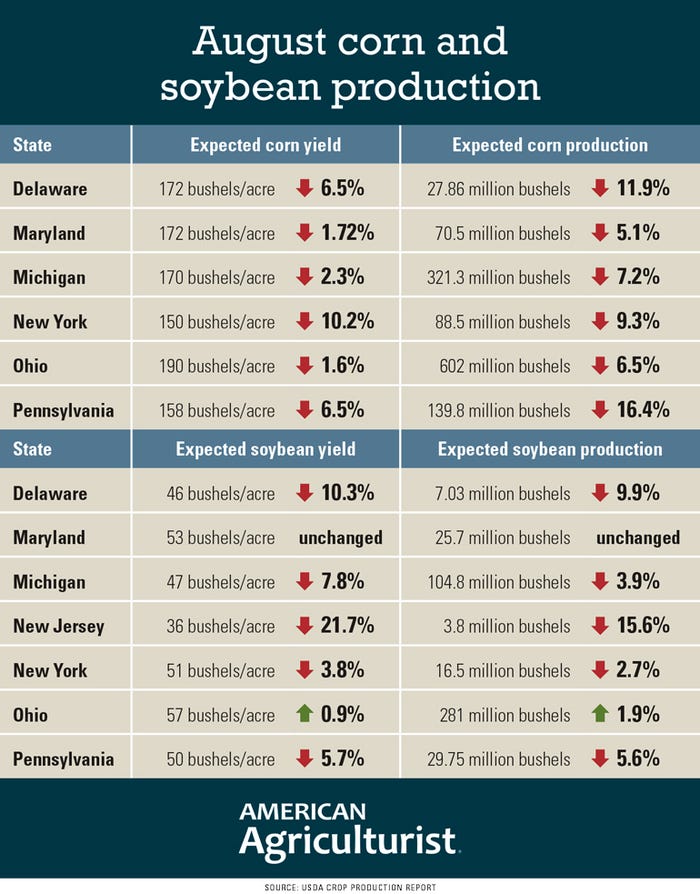

Officially, most of the region isn’t in drought, but it’s been a hot, dry summer. As a result, yields are down across the region, according to the August USDA Crop Production Report, the government’s first forecast for crop production during the season.

Check out the graphic to see what the crop production forecast is for your state.

Overall production is down in most states, a combination of lower yield and less acres planted. The latter is especially true in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic.

Ohio is the largest producer of corn and soybeans in the region. Growers planted more soybeans — 4.9 million acres — than corn this year — 3.17 million acres — and the state’s anticipated record soybean harvest shows that.

“Spring planting was delayed due to cold, wet conditions, which negatively impacted potential corn yields; however, soybean planting, which started behind schedule, was able to wrap up on time or earlier than the five-year average on most farms,” wrote Cheryl Taylor, Ohio USDA state statistician, in the state’s crop production report.

Michigan growers also planted more soybeans this year — 2.2 million acres — than corn — 1.89 million acres — but the dry weather has taken its toll on both crops.

“Spring planting was delayed due to cold, wet conditions. The state has experienced drier-than-normal growing conditions, and the central and thumb regions have been abnormally dry. Passing rains have helped to sustain field crops, though later-than-normal planting and these dry conditions are anticipated to have a negative effect on crop yields,” wrote Marlo D. Johnson, regional director of the USDA-NASS Great Lakes Regional Office.

The effects of the dry weather can really be seen in Cooke’s hayfields. He grows more than 1,200 acres of mulch hay for the mushroom industry and 400 acres of “horse-quality” hay. First cutting was good enough to fill an entire barn with hay, he says, but he only got around to mow second-cut orchardgrass last week.

“It’s really thin. There’s definitely going to be a shortage of that this year,” he says, but he added that last year’s plentiful harvest left with lots of crop carryover.

Across the Delaware River in New Jersey, where he sells seed to local farmers, hayfields are even drier, and he anticipates an even bigger hay shortage there.

One bright spot this season, he says, was his winter wheat, which yielded more than 100 bushels per acre, on average. “I should’ve entered the [wheat] contest because I’m sure some of those field yielded 150 bushels,” he says.

Buckeye view

Eric Tipton farms 1,000 acres each of corn and soybeans, and 300 acres of wheat, as well as 700 acres of custom work for a neighboring dairy in southwest Ohio’s Fayette County.

While he’s seen worse spring planting seasons, this year was a challenge with spring rains being both a blessing and a curse.

“We used every single window we had, and probably did some things we shouldn't have,” Tipton says. “With too much rain in short periods of time, we were constantly trying to find the right timing to do the right thing.”

Planting finished up in early June. “We had some timely rains that helped turn the corner for most of our crops,” says Tipton, who farms with Gene and Jo Baumgardner at Ricketts Farm and is transitioning into the primary operator.

They apply fungicides on corn and beans. “We haven’t seen a lot of disease or pest pressure, but with our weather patterns that include heavy dew and moisture that hangs around longer, as well as some timely rains in August, a fungicide offers some preventative protection,” explains Tipton, who predicts yields will be about what they were last year.

He’s not expecting any records this year, particularly because of heavy spring rain injury. “But we’re optimistic and hopeful we will hit the 220 mark [bushels per acre] for corn — a little above average — and we expect our beans to be above average as well.”

Nate Bair admits he has some crops struggling, but overall his crops in Wyandot County, Ohio, look “pretty good.” With his father, Neil, and brother, Ryan, they are farming about 600 acres — 213 acres of soybeans, 215 acres of corn, 138 acres of wheat and 30 acres of hay — about an hour northwest of Columbus.

“We had a small planting window in the middle of May before we got rained out and didn’t get back in until the first part of June,” Bair says. “We didn't finish planting — in less-than-ideal conditions —until June 3. We got little rains here and there before it turned dry into July.”

Now, rain has returned, and the rest of August is forecasted to be wet. Fields are spotty and given all the constraints, “if we do 50 [bushels per acre], I’d probably be pleased,” he says, noting it’s just a bushel shy of last year’s average.

For corn, he’s looking at about a 160 average, below last year’s average of 177. Some of his best fields planted in mid-May had a lot of ponding and many had to be replanted. “Our later corn looks pretty good, but it had to endure some really hot weather when it was starting to pollinate,” Bair says.

Michigan checkup

Mike Schwab says he feels blessed when he looks across the 800 acres he’s farming in the Bay County area of east mid-Michigan. With his grandpa Vern, dad Fred, and brother Eric, they planted 100 acres of sugarbeets and split the remaining acres evenly between corn and soybeans.

“After a dry June, we had ample rain in July and early August,” he says. “We feel fortunate because we know that’s not the case when you drive around the country.”

So far, he’s not noticed any major disease pressure. “With the leaves not getting on the ground, it hasn’t been picking up the fungus.”

A limited outbreak of tar spot was detected last year in early-mid-September, but Schwab says there was no yield reduction, and, in fact, it was one of the farm’s better years. “We’ve been scouting for it this year, but we’ve decided to not spray,” he says.

With continued timely rains, he expects yields to be on par with farm averages of about 180-190 bushels per acre of corn and about 50-60 bushels per acre of soybeans. “Last year we were just above 200 in corn, but I’d be surprised if we hit that mark this year,” Schwab says.

Scott Miller’s corn is alive, but drought conditions sucked its yield potential down. “It looked like a pineapple field all curled up,” he says.

He’s working about 2,500 acres 40 minutes northeast of Lansing, Mich., on land that touches four county corners — Clinton, Gratiot, Saginaw and Shiawassee. “We’re in a pocket that missed all the rain,” says Miller, who farms with his son, Damien, and wife, Jane. “We were extremely dry in June, July and through pollination, and combined with extreme heat, it’s not a good outlook.”

Recent rains have brought some color back to the corn, but he thinks the damage has been done. Soybeans, however, are “responding well to the moisture and are doing really well,” says Miller, who has his ground split between corn and soybeans this year because the wet fall prevented wheat planting.

Here’s a look at small grain production estimates from the Crop Production Report:

Oats

Michigan: 1.86 million bushels, 62 bushels per acre

New York: 2.69 million bushels, 69 bushels per ace

Ohio: 1.65 million bushels, 66 bushels per acre

Pennsylvania: 2.8 million bushels, 60 bushels per acre

Alfalfa

Michigan: 1.08 million tons, 1.9 tons per acre

New York: 576,000 tons, 2.4 tons per acre

Ohio: 990,000 tons, 3.3 tons per acre

Pennsylvania: 1.24 million tons, 3.1 tons per acre

All other hay

New York: 2.33 million tons, 2.2 tons per acre

Ohio: 1.36 million tons, 2.4 tons per acre

Pennsylvania: 2.3 million tons, 2.3 tons per acre

National view

Corn production is forecast at 14.4 billion bushels, down 5% from last year. Yields are expected to average 175.4 bushels per acre, down 1.6 bushels from last year.

Soybean production is forecast at a record high 4.53 billion bushels, up 2% from 2021. Yields are expected to average a record high 51.9 bushels per acre, up 0.5 bushels from 2021.

Total planted area, at 88.0 million acres, is down less than 1 percent from the previous estimate.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like