October 21, 2022

Illinois dicamba complaints are the lowest they’ve been since the product’s approval for use on soybeans in 2017. So, why are complaints decreasing? The answer is highly contested among industry experts.

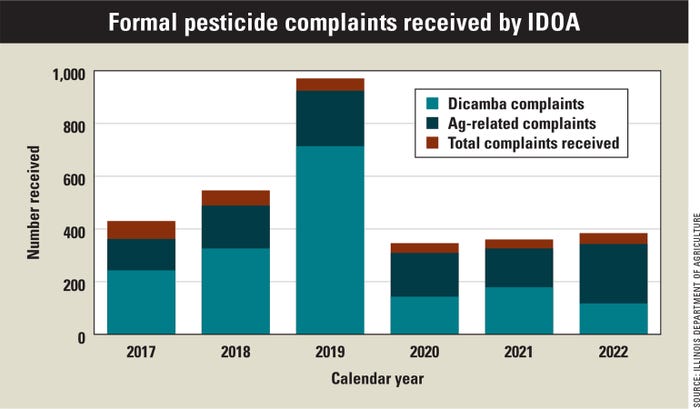

There were 119 formal dicamba complaints as of Oct. 7, down to a fraction of the complaint peak of 723 in 2019. But documented numbers have the potential to change as more reports are finalized.

“We’re still early in our reviews of the complaint season,” says Brad Beaver, acting bureau chief of environmental programs for the Illinois Department of Agriculture. “The investigators have been to all of the sites, but as complaints are under review, the numbers could go up or down. Any complaints are more than we would like, but it’s good to see that we have a steady decline.”

Although numbers seem to be trending in the right direction, questions remain about if enough action has been taken.

“When you’re talking about dicamba in a state where you’re growing about 10 million acres of the most sensitive plant species to dicamba movement, no volatility and low volatility have very different outcomes,” says Aaron Hager, crop sciences professor at the University of Illinois.

The why

Beaver believes that the state-specific restrictions in IDOA’s administrative rules have helped the numbers move in the right direction.

For the 2022 growing season, the following restrictions were in place for dicamba applications to soybeans:

Do not apply dicamba if the air temperature is above 85 degrees F.

Do not apply after June 20.

Do not apply where wind is blowing toward adjacent residential areas.

Must consult FieldWatch sensitive crop registry before application.

Do not apply when the wind is blowing toward any adjacent Illinois Nature Preserves Commission site.

“The two keys are the 85-degree temperature restriction and the June 20 cutoff date,” Beaver says. “I think those have played the biggest role in the reduction of cases.”

Beaver also admits there are several influences at play in the number of complaints.

“With any misuse, not just dicamba, there are always a lot of different factors,” he explains. “For instance, weather plays a big role on symptomology and how the plant responds and recovers. We’ve also had discussions on if people are filing all the complains or if there is damage that goes unreported.”

According to Hager, complaints have decreased for two different reasons:

There’s been a shift in acreage away from dicamba varieties to Enlist or E3 varieties, so less total dicamba is being sprayed.

What he calls “dicamba fatigue” from filing complaints but never seeing any corrective measures taken — so damage is still occurring, but complaints aren’t being filed.

“Don’t let anybody ever mislead you — the biggest driver is simply the fact that folks are worn out,” Hager says. “They’re just tired of filing a complaint and having very little satisfaction at the end of it.”

Hager says many of the complaints are driven by volatility rather than physical drift. To the industry’s credit, dicamba exposure from physical drift and contaminated equipment has decreased dramatically, he says.

“Volatility is a property of the herbicide itself, and it’s driven by environmental conditions,” Hager explains. “I’ve said it 101 times — you cannot label off volatility. You can’t write that statement on the label and magically make it go away.”

The future

The biggest unknown is what action U.S. EPA will take for the 2023 growing season.

“It’s in EPA’s hands right now whether there will be more restrictions or major label changes,” Beaver says. “Based off of what they do, as a state we’ll have to look into what restrictions, if any, we’ll impose as well.”

There are also questions about the effect complaints will have on dicamba use in corn.

“My concern is that because of all the off-target instances that have resulted from its use in soybeans that it could potentially impact the future availability of dicamba,” Hager says. “I can grow soybeans without dicamba in Illinois, but I’m going need dicamba to grow corn very soon. If we lose availability of it, we’re going to have huge issues in trying to manage weeds in corn.”

Hager says he’s repeatedly seen instances where 8- to 12-inch weeds are sprayed, and that this practice reduces the effective lifespan of dicamba via resistance. All postemergence-applied herbicides should be administered when weeds are 2 to 4 inches tall.

“There’s really not a lot of new chemistry in the marketplace or being developed right now,” Hager says. “So, it’s important to take care of what we have while it still works, or one day we may wake up and there won’t be much that works anymore. It’s not a very pretty picture when you think about it.”

Apply golden and silver rules to pesticide use

Matt Montgomery, field agronomist for Pioneer Hi-Bred, says the ag industry should draw its attention to the golden and silver rules.

The golden rule. Do unto others as you would have done to you.

The silver rule. When you use something, return it better than you found it.

Both principles, he says, can be applied to pesticide use.

“Why do we want to follow the rules when we apply pesticides?” Montgomery asks. “One reason is, I want to keep that material on target because I sure wouldn’t want somebody to have it move onto me, right? That’s the golden rule.”

The other reason to manage pesticides responsibly is because they’re a common pool resource — or a resource that is limited and can be depleted via resistance or public goodwill. Pesticides can be lost through either resistance or regulation, and both are equally permanent.

“If I want to hand things off better to the next generation, I would really like them to have a better weed management toolbox than we have right now,” Montgomery says. “Our toolbox is growing smaller because of resistance and sometimes regulation. I want to leave a toolbox that’s wide and deep, but that toolbox increasingly looks more shallow and narrow.”

Montgomery believes if everyone could adopt the golden and silver rules, the ag industry would be handed off better to the next generation.

Read more about:

DicambaAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like