July 14, 2020

There is no question that dicamba herbicide injury across the Iowa landscape in 2020 is the most extensive it has been since the introduction of dicamba in the 1960s. Iowa State University Extension field agronomists and commercial agronomists in several areas of the state report nearly all non-dicamba resistant soybean varieties are showing symptoms characteristic of dicamba, and in many fields the injury is fence row to fence row.

This is not the type of injury observed in the past; it’s at a landscape level. The focus over the past three years has been on postemergence dicamba applications on dicamba-resistant soybeans. This year it is apparent the problem is not that simple.

This article will describe factors believed to have contributed to this year’s problems.

The court decision

On June 3, the U.S. Court of Appeals canceled registration of dicamba products used on soybean crops, creating turmoil in soybean regions across the U.S. Although many state regulatory agencies stated they would not enforce the ruling and eventually EPA delayed withdrawal of registration until July 31, people who had planted dicamba-resistant soybean varieties were concerned about how they would control herbicide-resistant waterhemp and other weeds.

Soybeans across the state were reaching the stage appropriate for postemergence applications at the time of the ruling (71% of Iowa’s soybean were planted by May 10). It is likely that some applicators made poor decisions regarding appropriate application conditions based on fears dicamba would be made unavailable for use in 2020.

Environmental conditions

The 2020 growing season got off to a strong start with a record pace for planting both corn and soybeans across most of the state. This resulted in soybeans reaching susceptible stages when early applications of dicamba were being made to corn, and in many areas, there was an overlap between dicamba being sprayed on corn and soybean crops; these two things do not coincide so closely in many years.

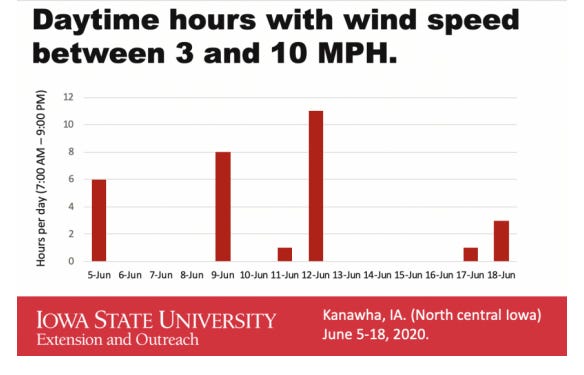

While conditions were great for getting the crop in the ground, weather conditions offered few days ideal for applying herbicides. For example, in north-central Iowa in the two weeks following the court ruling, wind speeds during the day averaged greater than 12 mph for 10 of the 14 days, resulting in a total of 40 hours during that time period when daytime wind speeds were between 3 and 10 mph (see accompanying chart). Daily high temperatures exceeded 85 degrees F on five of those days.

Weather conditions limited opportunities to get fields sprayed, resulting in large quantities of dicamba being applied in a small time period. Limited rainfall during this period left dicamba on soil and foliar surfaces for extended times where it is prone to volatilization during hot periods.

Use on corn

Dicamba use in corn has increased in recent years due to the spread of waterhemp biotypes resistant to Group 5 herbicides (atrazine), Group 9 herbicides (glyphosate) and Group 27 herbicides (HPPD inhibitors). Several agronomists have reported dicamba being used for late postemergence applications after earlier treatments performed poorly.

In addition to more acres being sprayed with dicamba, the rates of dicamba applied per acre have increased for multiple reasons:

Resistance more common. Relatively low rates of dicamba had often been used to supplement other products. As resistance became more common to other products (Group 5, 9 and 27), dicamba rates were increased to the full label rate for postemergence applications (0.25 pound per acre)

Straight dicamba use. Marketing programs in 2020 resulted in movement from Status (dicamba plus diflufenzopyr) to straight dicamba products. The diflufenzopyr in Status allows dicamba rates to be reduced by 50%, and the switch to straight dicamba products resulted in more dicamba per acre being applied.

Higher volatility with corn. Nearly all of the dicamba products used in corn are formulations higher in volatility than the formulations registered for use in dicamba-resistant soybeans. Dicamba use in corn also has a lot of flexibility in terms of drift reduction practices compared to the unprecedented restrictions placed on dicamba use in soybeans.

Nearly everyone in agriculture recognizes the widespread injury to soybean fields this year is not acceptable. Weed scientists in the Delta region of the U.S. coined the term “atmospheric loading” to describe the problems their region experienced with dicamba movement. Atmospheric loading refers to so much dicamba moving into the atmosphere that it is difficult, if not impossible, to identify the specific application that resulted in injury to a field. This is what appears to have occurred across much of Iowa in 2020.

No simple solution

There is no simple solution to this problem — other than reevaluating dicamba use in corn and soybeans. The current labels for dicamba products used on soybeans are so strict that any additional application restrictions would essentially render dicamba useless for waterhemp control. New formulations of dicamba with lower volatility than current products are being evaluated and are projected to be in the marketplace in the future, pending regulatory approvals.

These formulations are expected to be used in Xtendflex soybean varieties (resistant to dicamba, glyphosate, and glufosinate). Significant reductions in volatility and better drift management practices could greatly reduce risks associated with dicamba, and these formulations probably should be mandated for use on corn and for other dicamba uses where appropriate.

While most of the focus is on the damage done to soybean crops because of their high sensitivity to dicamba, it is not difficult to find injury symptoms on other plants in the landscape. Continuing down this path will only result in more restrictive rules for use of dicamba and other pesticides. Herbicides will continue to be the backbone of agricultural weed management for the foreseeable future, but they need to be used as part of an integrated management program in order to protect their effectiveness and reduce negative impacts to the environment.

Hartzler and Jha are Iowa State University Extension weed scientists. They can be contacted at [email protected] and [email protected].

Source: ISU, which is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

Read more about:

DicambaYou May Also Like