If you waited to apply anhydrous ammonia until this spring, it may not have been a bad corn management financial decision.

High fertilizer prices were a hot topic at the University of Missouri Crop Management Conference. “Farmers made good money in 2021,” MU Extension economist Ray Massey says. “They want to make sure that they make good money in 2022, and they're willing to fertilize for it.”

He offered insight into a few crop management scenarios for farmers dealing with soaring fertilizer prices.

Know N return

When it comes to nitrogen, Massey says, the first nitrogen applied in a field is worth more than the last.

“We normally think of nitrogen as having what's called a quadratic plateau, meaning when you first put on nitrogen, it gives you a huge bump,” he explains. “And then later on, it gives you a less of a bump and then less of a bump until it just finally plateaus.”

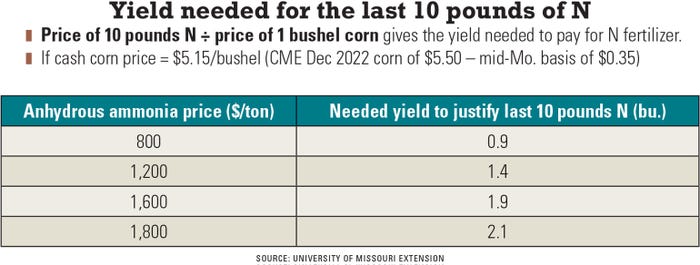

So, farmers must decide just how many corn bushels they need to pay for that last 10 pounds of nitrogen to make the economics work for their farm. Quick math explains it.

According to the data, Massey says there is a point where farmers are not realizing the extra bushels and are simply wasting money on nitrogen application. Then, it is time to rethink fertilizer strategy.

There is an economic signal, in Massey’s mind, where prices become too costly, and farmers should scale back planting corn acres or apply less nitrogen.

Spring-applied works

When faced with rising nitrogen prices, some farmers question if supply will even be available, or more so if it will be available at the time needed. Then they question application timing. Should it be fall- or spring-applied anhydrous, or fall and then rescue treatment in the spring because of nitrogen loss? These are all valid questions when weighing fertilizer options, Massey says.

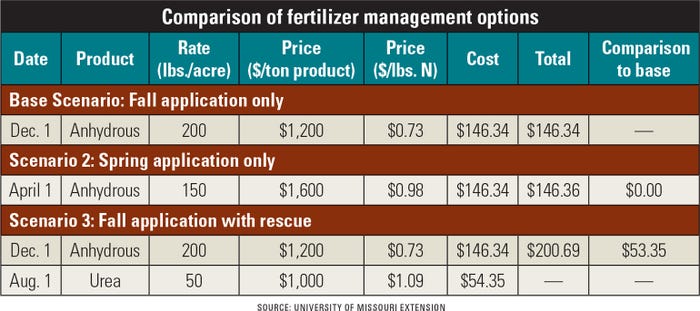

So, he looked at application timing of nitrogen along with price to see how much it would cost to delay application of anhydrous ammonia, or if farmers put on fall application and then need a rescue treatment. To account for any type of denitrification, he applied at higher rates in fall versus spring.

What Massey found was whether fertilizing in fall or right before planting, there was no difference in price cost per acre, even if anhydrous went up $400 per ton.

Here’s how it breaks down:

He notes that farmers who waited to apply fertilizer this spring, even if anhydrous reaches $1,600 per ton, will be breakeven on price. However, if corn farmers who applied in fall lost nitrogen over the winter months, there will be a cost to make it up this spring.

While Massey says he is not sure how high prices will go, this type of analysis provides a framework for farmers making decisions on application timing in relation to cost and nitrogen loss.

Adjust your budgets

In all of Ray Massey’s years as a University of Missouri Extension economist, he has never been called by the associate dean of the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources regarding his online crop production budgets, until now.

Massey, who puts together budgets to assist Missouri farmers in evaluating expected costs and returns for crop and livestock enterprises, says the soaring cost of fertilizer created problems for this year’s budgets and had farmers and other agriculture industry stakeholders asking questions.

The MU Extension economist creates the budgets in October. At that time, he estimated $800 per ton for anhydrous. The price quickly exceeded those estimates and by the end of November, when many farmers and lenders pull together budgets, reached above $1,300 per ton. “I don’t think I have ever seen a rise like that for nitrogen,” Massey says. “It rose very rapidly.”

So budgets, even university budgets, need to be adjusted. The University of Missouri offers insight into 2022 costs estimates for each crop or livestock enterprise. It also has a free downloadable budget for farmers to run management scenarios with university costs or input their own actual costs. It can be found by scrolling down the left side of the page.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like