Jacob Tribble and Hunter Burks see advantages and opportunity in drones. Ginger Rowsey

Agricultural drone spraying is no passing fad — at least according to KD Bohon.

Bohon is the Business Development Manager at Agri Spray Drones, so, of course that’s what you would expect him to say. But a captivated audience at a recent spray demo in Jackson, Tenn., tells its own story. As do the numbers of spray drones heading to farms.

“We’ve sold around 350 units just this summer,” said Bohon, “which is a huge jump over the previous year. This technology is really gaining momentum.”

Bohon demoed the Agras T-30, an 8-gallon spray drone that can cover 30 acres per hour on average, according to the company. After importing a field boundary and parameters, the drone flies autonomously, returning to the loading site when the tank is empty and batteries need charging.

“Typically, people who see the drone in action are very impressed,” Bohon said. “We still get some skeptics who say, ‘If I can’t get 600 acres a day, I don’t want it.’ But many of our users have found that in certain circumstances the drone is better than planes or choppers because the timing is optimal.”

One such user is Hunter Burks, a farmer in western Tennessee who purchased two drones from Agri Spray after seeing a spray demo in a fellow farmers’ field.

“I think it’s really going to be something,” Burks said. “How many times when we need to be spraying is it either too muddy to get in the field, or we can’t get a plane scheduled? Wait long enough and that adds up to yield lost. I see a lot of opportunity with drones.”

Burks and friend Jacob Tribble have teamed up to test drone spraying on the Burks’ family operation near Halls, Tenn., this season. From the results they’ve seen, they plan to launch a commercial application business in 2023 — Southern Ag Drone Solutions.

“Many people want to see these demonstrations because it’s cool, but then they see that drone spraying is also effective, and they’re interested in trying on their own farms. We see a lot of potential uses — spraying fungicide and insecticide in crops, applying foliar feed in hay fields, you could do some spot spreading of fertilizer. I plan to plant some food plots with it this fall,” Burks said.

As interest in drone spraying increases and farmers begin to experiment with this new venture, it’s clear there are advantages to the technology — timely applications on hard-to-reach fields, flexibility in usage, as well as opportunities for new business ventures in rural areas.

But there are factors that call for serious consideration, as well. What are the requirements of drone pilots? Is it more cost effective to buy your own drone or contract with custom applicators? Do you have the time and labor resources needed to spray efficiently with a drone? And most importantly, does it work?

Drone spraying efficacy

In 2019, Kiersten Wise, a plant pathologist with the University of Kentucky, realized some corn growers in her state were finding it more difficult to make timely applications of fungicide. Wise attributes this to the growing number of Midwestern farmers who had begun applying fungicides and competing for crop dusters. Kentucky is also dominated by small, irregularly shaped fields that make aerial applications difficult, if not impossible.

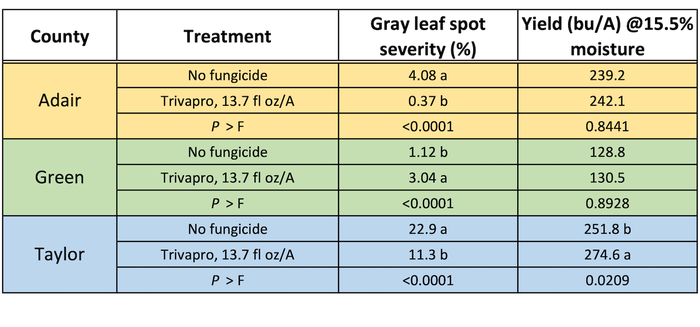

She began a proof-of-concept study for drone spraying. Testing three corn fields with gray leaf spot disease.

An early concern for Wise was low spray volumes with drone applications (1-2 gallons per acre). Would these low volumes pose challenges in achieving adequate coverage? Could drone spray reach into the canopy down to the lower leaves?

Her research found that canopy coverage with the drone was comparable to ground applications and adequate throughout the plant. Fungicide applied with a drone reduced gray leaf spot in all three trial locations. In areas where disease pressure was high, yield responses were observed, which is similar to aerial and ground application results, according to Wise.

“This study indicates that drone fungicide applications may be a viable application method for farmers, especially in areas where aerial and ground application are difficult or not available,” said Wise.

Wise advises growers to interpret results with caution, however. Published university studies on drone spraying efficacy are still limited.

Costs and learning curve

If drones are a solution to timely applications of pesticides, the next question may be should I buy my own drone or contract with a commercial applicator? Most commercial drone applicators are currently charging $11-14 per acre — rates that are competitive with traditional aerial applications.

To operate your own drone may only cost $1 per acre, but there is the upfront investment of the drone itself, a trailer to haul it, generators to charge batteries, water tank, mixing tank, insurance and license fees.

Wise, Burks and Tribble all caution that learning to operate a spray drone is a timely endeavor.

“When it comes to operating your own drone, time may be the biggest barrier to entry for some farmers,” Wise said.

Before flying, even on your own farm, operators need a drone pilot’s license, an aerial applicator’s license, a state pesticide applicator’s license, an FAA physical, and certificates of exemption to fly a drone over 55 lbs. If you plan to fly at night that’s another certification. As is flying a swarm of drones.

“It can feel overwhelming when you look at all the studying and preparation that is needed to be able to fly a drone,” Tribble said. “You’ll need to devote several weeks to studying for the drone pilot’s license. There is a lot of preparation involved in collecting documentation and working with different agencies.”

Many drone companies will provide a service that helps operators navigate regulations as well as insurance needs. Burks and Tribble used this service, and said it was a valuable investment. Still, the process took more than six months to complete.

Learning to fly the drone may take longer than expected, even for those who have previous drone training.

Both Burks and Tribble had experience operating small drones but admitted there was a learning curve with flying the larger spray drone.

“You go from flying a 1-pound drone to a 160-pound drone fully loaded and it is much harder to stop,” said Tribble. “That was an adjustment that required some extra training on our part.”

“Flying the drone is harder than they make it sound,” said Burks. “When the drone senses obstacles, like trees or a center pivot, you have to manually adjust. You can’t just set back and let it fly itself.”

Then there is the actual spray application process. The Agras T30 can spray about 4 acres per tank load and cover up to 40 acres per hour according to Agri Spray’s website. Burks said don’t expect to be that efficient right away.

“Until you become comfortable with flying the drone and get in a rhythm with changing batteries and refilling the tank, you should probably expect to average about 20 acres per hour,” he said.

“As a farmer, you have to ask yourself if you have time to commit to that,” he added. “If not, you would need an employee to devote to it,” he said. “I think using commercial applicators will be more efficient and cost effective for most farmers.

Opportunity

As Burks and Tribble have experimented with the technology, they are confident drone sprayers have a place in agriculture.

“Fungicides will be our primary focus, but it works well with insecticides and most herbicides, too,” said Tribble.

In Burks and Tribble’s on-farm trials, they reported that in wheat fungicide tests the drone performed well and provided adequate coverage.

“The drone may not apply the same level of coverage as a ground rig, but with the drone you’re not running over the crop,” Tribble said. “And you can apply when needed and not have to wait for the ground to dry up.”

In addition to large row crop acreages, Burks sees promise for drone applications in pastures and hay fields.

“Many hay fields have never had an option for aerial because they’re small and irregular. This will appeal to them more. It allows you to get in the corners and closer to the tree line than traditional aerial applications,” he said.

Another benefit — neighbors never hear the drone.

“You don’t receive the noise complaints from neighbors that you get from other applications. Your neighbors will probably not even know you’re applying it,” he added.

“I think some people are still skeptical, but as more research comes out, I think they’ll come around,” he added. “Drone spraying is going to take off.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like