March 24, 2023

If there’s anyone in Illinois who knows corn rootworm, it’s Joe Spencer, a research scientist at the University of Illinois. Spencer has studied rootworm behavior for decades, achieving expert status on how both Bt traits and environmental events impact rootworm pressure. The future of trait resistance in the Corn Belt, he says, is troubling, to say the least.

“The best way to have a rootworm problem is to just keep growing corn,” says Spencer, who explains that continuous corn planted with traited hybrids has increased odds of resistance — and trait failure.

Few know this better than Jamie Walter of DeKalb County, Ill., who, in July 2021, was left with destruction, frustration and unanswered questions after a summer storm tore through the area.

In one day, nearly 500 acres of Walter’s continuous corn was flattened. Just one day before, the sea of green was ripe with optimism, eager for pollination. After the storm, hundreds of acres lay steamrolled as far as the eye could see. But why?

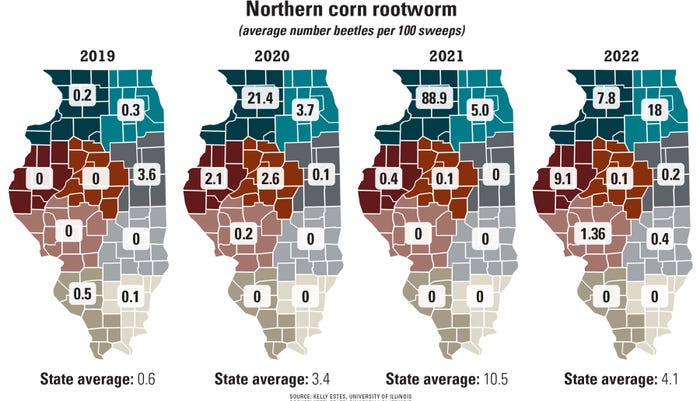

The mild, dry spring made for a straightforward planting season, and like many other farmers, Walter was hopeful for the crop year ahead. But beneath the surface, the soil told a different story — one of growing conditions that had also been ideal for the growth and hatch of rootworm larvae that were wreaking havoc on corn root systems. And it was happening all across northern Illinois.

“You could pull some of these plants out by hand, and most of the nodes were gone,” he says. “Emotionally, it’s a kick in the gut when you see that kind of damage.”

In a single growing season, the western and northern corn rootworm populations had increased dramatically. And the traited seed Walter had invested in didn’t protect the crop.

“We suffered what can really only be described as a technology failure on those fields,” Walter says. “On those 500 acres, we planted several different varieties of stacked rootworm traits, including both SmartStax and Herculex Xtra products.”

Walter invited representatives from each company to his farm to see the damage for themselves. They acknowledged significant feeding issues and pulled larval samples to test the next year’s eggs for Bt resistance. As of press time, neither company had shared results from 2021 tests.

According to Pioneer, the tests weren’t conducted until 2022, and results did not meet U.S. EPA’s definition of resistance. Pioneer claims this conclusion was shared verbally with the grower. Recollections may differ, but at the time, Walter didn’t find that information particularly helpful.

Adam Theis, Pioneer corn marketing lead, says that when growers have a concern that requires samples to be taken, timing is crucial.

“We try to get there as fast as we can to grab the adult populations before they leave,” Theis says. “There are times where that’s not achievable. And when that happens, we ask the farmer if we can retest the following year.”

Local agronomists speculated to Walter that the damage was because of resistance or instead due to a rootworm adaptation in the area.

“Resistance is evidence of adaptation to Bt,” says Spencer, adding that any local adaptation that’s genetically based and reduces pest susceptibility is, by definition, resistance.

Bayer and Pioneer both believe the unexpected damage that farmers have experienced across the Midwest could instead be the result of a high-pressure problem combined with a lack of crop rotation.

“Speaking in generalities, sometimes we get confused with higher rootworm pressure versus resistance in those fields,” says Safeer Hassan, Bayer corn systems manager. “A lot of times what’s happening is a higher-pressure buildup from years of planting corn, because in most of these cases, the grower is not rotating to soybeans.”

Other agronomists speculate that poor control may have been due to a delayed rootworm hatch, after the peak Bt protein expression from the SmartStax and Herculex Xtra products, resulting in poor control.

According to Spencer, research with single-trait hybrids on delayed rootworm hatch didn’t find significant effects on their survival.

“Maybe the stacked varieties have more variable expression of the Bt toxins, but I would be surprised if that were the case,” Spencer says. “I’d like to see the research.”

Dealing with loss

For the farmer, the loss is still the same.

“At the end of the day, it doesn’t make a lot of difference to me as a farmer,” says Walter, who’s seen 30- to 40-bushel-per-acre yield losses in heavy rootworm years. “If the technology itself isn’t working the way it’s supposed to, the fact is that I’m paying for a trait that isn’t giving us much value.”

He says that damage equates to $150 or more per acre, which adds up over a few thousand acres of corn. To the companies’ credit, Walter says they attempted to make up some of the financial loss, but “we certainly didn’t feel like we were made whole.”

According to Walter, Both Bayer and Pioneer recommended he rotate to soybeans or use granular soil insecticides on a non-corn rootworm-traited product on his acres for 2022, which he did. Walter says rootworm feeding was less severe, either because of different growing conditions or due to soil insecticides. Still, yields for 2022 weren’t as high as Walter expected, making him wonder whether rootworm populations are still feeding.

Spencer isn’t sold, explaining that granular insecticides aren’t intended to manage rootworm populations, but instead to protect roots where the granules are applied — meaning roots outside of that area are still vulnerable.

“Research showed that sometimes you can actually produce more western corn rootworm from plants treated with soil insecticides compared to untreated,” Spencer says. “The protection allows a root to proliferate to much larger size than it would if many nodes were pruned by larvae, so more root tissue available means more rootworms.”

The additional grower expense has raised questions, especially from northern Illinois farmers, as to the efficacy and value of Bt traits.

“If you look at doubling up the cost of control by using a soil insecticide and seed technology, you’re talking $25,000 to $50,000 of additional cost,” Walter says.

Theis adds that Pioneer’s best management practice recommends rotating from corn every two to three years to reset area rootworm populations, and to always follow the Product Use Guide to help realize the full potential and economic benefit of a long-term pest management plan.

Reality of resistance

“We’ll keep trying to find ways to adapt,” says Walter, noting that for 2023, he will continue using granular soil insecticide on corn-on-corn acres. He’ll continue to add soybean rotations and will continue his on-farm tests of traited varieties, soil insecticide and rotation.

Walter says he’s encouraged by the new SmartStax Pro RNAi trait, Bayer’s newest mode of action against rootworm, but he is concerned about the potential for resistance and trait mismanagement. Pioneer also has announced an RNAi stacked trait in its Vorceed Enlist varieties, which are in a pilot program for 2023 and will be readily available to growers in 2024.

“We don’t have enough new traits that are proven to be effective,” Walter says. “If we’re rolling out one new control mechanism at a time, will we see ongoing resistance issues? I don’t know, but it’s a concern. Mother Nature seems to find a way around these things.”

Hassan says SmartStax has been on the market for more than 10 years, and one-third of all U.S. corn acres are planted with corn rootworm traits. Resistance, he says, is a natural development — especially in those products that have been in the market for an extended period of time.

But trait management and stewardship are the keys to keeping traits effective. Hassan recommends farmers bring in new traits like Bayer’s RNAi trait to “bring a unique challenge for the insect to overcome.”

Back on campus, Spencer acknowledges the importance of Bt hybrids in the field but says rootworm populations have quickly developed resistance.

“Resistance reduces options. Growers who expect to protect their corn with Bt should also expect it not to work like it once did,” he says.

In Spencer’s trials, the introduction of RNAi was remarkably effective at controlling both northern corn rootworm and western corn rootworm.

“The bottom line is that compared to the other Bt traits, the new triple-stack hybrid using RNAi is really important,” he says. “Based on what we know about resistance, the efficacy of the triple stacks is attributable mostly to the RNAi mode of action. Cry34/35Ab1 still has a capacity to kill some local western corn rootworm; though in decline, it has proven to be locally more durable than the now ineffective Cry3Bb1 toxin.”

Theis is optimistic about the future of corn rootworm control and says Corteva is developing new modes of action for launch mid-to-late next decade.

Advice for future

The 2021 crop year undoubtedly shifted how Walter farms.

“Rootworm problems are real, whether it’s resistance or changes in behavior and hatching populations,” he says. “But there are some stack technologies that seem to have weaknesses that they didn’t used to have.”

He says it’s important not to assume that rootworm problems only exist in northern Illinois.

“I wouldn’t automatically assume that you don’t have a problem on your farm,” Walter says. “I certainly would be digging roots year after year, keeping an eye on my fields and keeping an ear out to neighboring counties on rootworm populations that might be expanding.”

Walter says the equipment for applying granular soil insecticide may be worth the investment. But his biggest takeaway? Don’t be afraid to ask questions.

“As producers, we need to speak up and pay for value,” Walter says. “When there’s technology value in a hybrid, as farmers, we should embrace that. But if there’s not value, we have to ask questions like, What am I paying for?”

Monitoring a must

A true entomologist, Spencer advocates for IPM, or integrated pest management, for growers to monitor their insect populations.

“Monitoring lets a grower know whether or not they can expect an economically damaging larval population,” Spencer says. “Combined with knowledge of which Bt traits are locally effective or not, a grower can follow a course of action that is best suited for his individual fields.”

Monitoring for pests can successfully guard against trait resistance and often save unnecessary expense.

“Bt doesn’t belong on every acre,” Spencer says. “If a grower doesn’t have an economic population of beetles, then using Bt varieties is like taking medicine you don’t need. We’re just continuing to select for resistance.”

Spencer says the best way to monitor for rootworm pressure is to put sticky traps in each field to gauge beetle population. Then depending on the number of beetles found, a decision can be made if planting Bt varieties, applying soil insecticide or rotating to soybeans is necessary.

“A grower’s options are increased if they monitor for pests,” Spencer says. “If you don’t monitor, you don’t know what the real situation is in your fields and are forced to listen to what somebody says at the coffee shop or to the guy trying to sell seed.”

A combination of strategies applied across the farm is often the best hedge against insect damage, but still, there’s no one-size-fits-all strategy.

“Being a farmer is tough,” Spencer says. “You can do everything right, and at the end of the year, you can still lose money through no fault of your own.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like