Wheat and malting barley are 10 days ahead of schedule on Jason Scott’s farm in Dorchester County, Md.

In fact, his malting barley has just started flowering, and this is the time when his management — and a little help from Mother Nature — will allow him to get a crop that will make, or break, his growing season.

“The wheat is looking great. It's ahead of schedule,” Scott says.

But it will soon be time for him to be on the lookout for fusarium head blight, the most serious disease of barley and wheat. Timing, wet weather, high humidity and higher temperatures increase the threat of fusarium head blight, or head scab. Severe cases can cause near 50% yield loss, and DON rejection or docking.

Flowering, which happens three to five days after wheat starts heading, is prime time for the fusarium fungus to develop. You also need at least 85% humidity and temperatures between 68 and 75 degrees F.

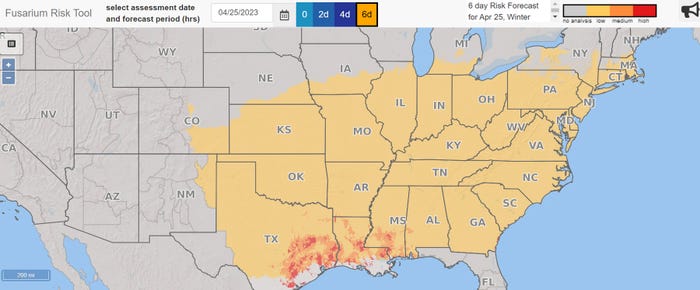

One of the best ways to assess your location’s risk for head scab is using the head scab risk assessment tool developed by researchers at Kansas State, Ohio State and Penn State. The tool uses weather and crop information to predict head scab risk up to six days out.

Currently, the risk for head scab across much of the region is low, but in areas where wheat and barley will soon be heading and the weather conditions are ideal, that risk will grow higher as the month goes on.

Barley and wheat are off to good starts in Delaware and Maryland. The most recent USDA Crop Progress Report shows more than half of barley acres in both states already heading, with 11% of Maryland winter wheat heading and 33% of Delaware winter wheat heading.

In a crop alert posted on the Fusarium Risk Tool website, Alyssa Collins, plant pathologist with Penn State Extension, said that fungicide applications should be applied when 50% of barley stems in a field are fully headed.

Caramba, Prosaro, Sphaerex and Miravis Ace give good control of most leaf and head diseases, in addition to suppressing scab, Collins said. Spray nozzles should be angled at 30 degrees down from horizontal — toward the grain heads — using forward- and backward-mounted nozzles, or nozzles with a two-directional spray, such as Twinjet nozzles.

Here are some more tips from a Penn State alert last year:

• Foliar fungicides should be applied at 50% heading or shortly thereafter. Once the crop starts heading, there is a five- to six-day window to apply a fungicide. Current labels state that the last stage of application is midflowering, and then there is a 30-day harvest restriction.

• Do not use any of the strobilurins (Quadris or Headline) or strobilurin/triazole (Twinline, Quilt or Stratego) combination products at flowering or later. There is evidence that they may cause an increase in mycotoxin production. The Miravis Ace label allows for earlier application than Caramba or Prosaro, but best results are still achieved when application is timed at heading in barley.

The Crop Protection Network, run by Cooperative Extensions around the country, has a “Fungicide Efficacy for Control of Wheat Diseases” guide. The guide is handy because it lists several fungicides and their efficacy against the most common barley and wheat diseases.

Plan of attack

Scott, who farms just under 2,000 acres in and around Hurlock, Md. — 900 to 1,000 acres of corn, 300 acres of malting barley, 400 acres of wheat followed by double-crop soybeans, and 300 acres of full-season soybeans — says he and his crop scout will soon be out scouring fields to see how the crop is growing. Flowering is the most critical time to get a fungicide on wheat, he says.

“The timing of that is critical,” he says, adding that he also has started growing scab-resistant varieties.

But “there is no silver bullet to it, unfortunately,” he adds.

Scott averages 85 to 90 bushels of wheat per acre, although he’s had some years when his crop reached 120 bushels per acre and some years where yields were as low as 50 bushels per acre, depending on growing conditions.

Mother Nature has not been kind to him the past two years. A spring frost two years ago right around pollination devastated his wheat crop. Yields in his worst fields were as low as 27 bushels per acre.

Last year, hail damaged 80 acres of his best wheat field, which averaged 56 bushels per acre. “It was right along Route 50. Some guys had fields that were completely obliterated,” Scott says.

The wheat that gets marketed right away goes to Perdue Farms while the wheat he stores on the farm — he has room for 50,000 bushels — gets sold through Hostetter Grains and eventually ends up in flour mills, mostly in Pennsylvania.

In recent years, Scott has started growing malting barley and has a contract to sell it to Proximity Malt in Delaware. “We have soils that do well with barley, and typically do pretty well with the soybeans," he says.

Proximity pays him a contracted price that he gets if the barley reaches quality standards set by the maltster. However, the price can revert to a market price if those standards are not met, he says, which ups the game for his management.

“It’s definitely a little more risky than regular barley,” he says.

Read more about:

BarleyAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like