The recent wet weather, combined with higher humidity and higher temperatures in the forecast, means that the threat of fusarium head blight — or head scab — is increasing.

Head scab is the most serious disease of wheat and barley. Severe cases can cause near 50% yield loss, and DON rejection or docking.

Flowering, which happens three to five days after wheat starts heading, is prime time for the Fusarium fungus to develop. You also need high humidity — at least 85% humidity — and temperatures between 68 and 75 degrees F.

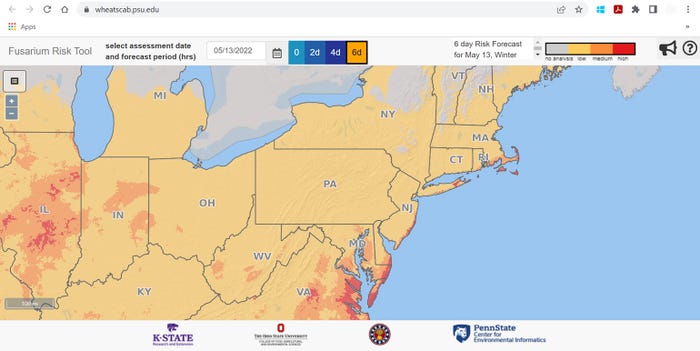

One of the best ways to assess your location’s risk for head scab is using the head scab risk assessment tool developed by researchers at Kansas State, Ohio State and Penn State. The tool uses weather and crop information to predict head scab risk up to six days out.

The weather earlier this week was humid and rainy in many areas. Across Delmarva, central Maryland and southern New Jersey, where wheat and barley has already started to head, the risk for head scab was high.

Overall, barley and wheat are off to a slow start, likely because of the cold, wet conditions last month. In Maryland, 55% of barley is heading, according to the most recent USDA Crop Progress Report, which is ahead of last year’s pace of 44% but behind the five-year average of 71% headed for this time of year. Winter wheat is further behind, only 35% headed, well behind the average of 80% headed.

Delaware barley is 85% headed, which is average for this time of year, and wheat is 71% headed, also about average.

About 35% of barley is heading in Pennsylvania, and 10% of winter wheat is heading, according to the report.

A Penn State Extension alert from last year listed tips for foliar fungicide application once the threat for head scab heats up:

Foliar fungicides to protect barley from scab should be applied at 50% heading or shortly thereafter. Once the crop starts heading, there is a five- to six-day window to apply a fungicide. Current labels state that the last stage of application is midflowering, and then there is a 30-day harvest restriction.

Do not use any of the strobilurins (Quadris or Headline) or strobilurin/triazole (Twinline, Quilt or Stratego) combination products at flowering or later. There is evidence that they may cause an increase in mycotoxin production. Caramba, Miravis Ace and Prosaro all provide good scab suppression. The Miravis Ace label allows for earlier application than Caramba or Prosaro, but best results are still achieved when application is timed at heading in barley.

Spray nozzles should be angled at 30 degrees down from horizontal, toward the grain heads, using forward- and backward-mounted nozzles or nozzles with a two directional spray, such as Twinjet nozzles.

The Crop Protection Network, run by Cooperative Extensions around the country, has a “Fungicide Efficacy for Control of Wheat Diseases” guide. The guide is handy because it lists several fungicides and their efficacy against the most common barley and wheat diseases.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like