Think DifferentGlyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth is a predicament that could have been avoided “if we hadn’t used only glyphosate year after year after year,” says Evansville, Ind., farmer Joe Steinkamp, a director of the Indiana Soybean Alliance.Steinkamp is battling the resistant weed on his farm, where it arrived with floodwaters. To stay ahead of this aggressive species, he’s spending three times as much money on soybean weed control as he did three years ago.He says adopting an integrated weed management program that deploys multiple effective modes of action “is our duty, not only to protect our livelihood today, but for the future.”

August 28, 2013

On July 6, 2011, Joe Steinkamp changed his entire weed-management program.

Steinkamp raises seed soybeans and white corn on Ohio River bottomland near Evansville, Ind. On that July day two years ago, his neighbor brought over some weeds that had survived Roundup. “He said, ‘Joe, do you know that these are?’ I said, ‘I sure do!’ ”

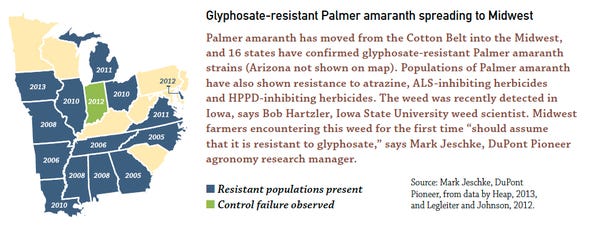

Just the day before, Steinkamp was in Tennessee with the Indiana Soybean Alliance to see the ravages of an aggressive pigweed that is rapidly moving north into Corn Belt states. Palmer amaranth is a faster-growing and more competitive cousin of common waterhemp, and it’s frequently resistant to glyphosate and other herbicides.

After seeing his neighbor’s soybean field thick with uncontrolled Palmer amaranth, Steinkamp went looking on his own farm. He discovered foot-high infestations in both soybeans and corn. The seeds probably arrived with Ohio River floodwaters, he says. He also spotted the weeds in drainage ditches.

“Palmer pigweeds can produce up to half a million seeds per plant. And they are easily carried by water, wind, tillage tools, combines; even on your clothes,” Steinkamp says. In Michigan, where the weed was first detected in 2010, the tiny seeds were probably transported in cottonseed fed to dairy cattle and spread to fields in the manure.

Early weed detection and aggressive management are essential, says Christy Sprague, Michigan State University weed scientist. “It’s difficult to control, especially in soybeans.” In fields where it’s not correctly identified or managed, a few plants “can rapidly multiply to several hundred plants in just a year’s time.”

Integrated weed kill

To kill Palmer amaranth that first summer, Steinkamp says, “We got out the hoes and chopped them.” Then he worked with a crop consultant to plan a new strategy.

“Palmer amaranth has to be managed in an integrated system,” says Aaron Hager, University of Illinois weed scientist. “You can’t just throw one herbicide at it.” The key elements for control are:

Plant into a clean seedbed

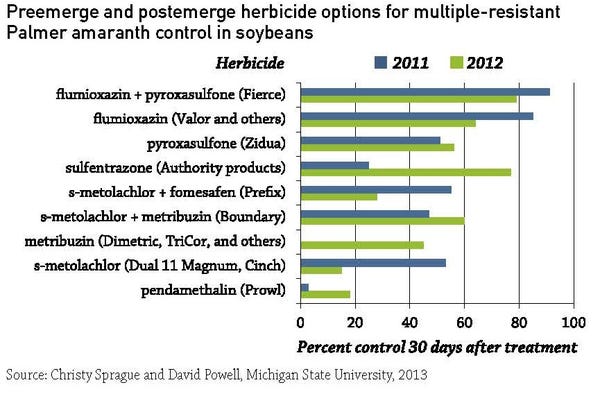

Use full rates of a preemergence residual herbicide that kills Palmer amaranth

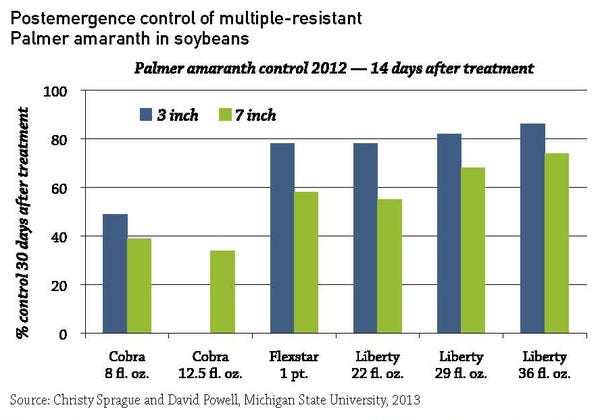

Apply timely postemergence herbicide before Palmer pigweeds are 3 inches tall

Tank mix another residual herbicide with application to extend control

Come back with a second postemerge application if needed

Remove surviving plants by hand or mechanically

“The key to management of Palmer amaranth is to control it at its most vulnerable stage — germination,” says Travis Legleiter, Purdue University weed specialist. “The use of preemerge residual herbicides is critical in both corn and soybeans.”

Steinkamp was already using residual herbicides in corn, where there are quite a few options available for controlling Palmer pigweeds. In heavily infested fields, growing corn for several years is recommended to lower populations, Legleiter says.

In soybeans, options for control are limited. Steinkamp’s previous weed program relied on tillage or a burndown of glyphosate plus 2,4-D, followed by one post-emergence glyphosate application. That program was working fairly well before glyphosate-resistant Palmer showed up, he says, although “we were worried about developing waterhemp resistance, but hadn’t taken any action yet.”

Steinkamp’s new plan starts, as usual, with clean fields. Immediately after planting, he sprays a soil-applied residual herbicide on both corn and soybeans. On conventionally tilled soybeans, he’s had good results with Authority XL. His backup plan in case of weather delays is an early postemergence tankmix of Warrant and Roundup PowerMax.

That’s followed about four weeks later by a postemergence application of herbicide with overlapping residual activity. He likes Flexstar GT, which has both burndown and residual action.

Growers should be aware that herbicides may not completely control Palmer pigweeds, notes Mark Jeschke, DuPont Pioneer agronomy research manager. “Cultivation or hand weeding may be necessary to prevent escaped plants from producing seeds.”

Stick with the plan

Steinkamp’s strategy worked well in 2012, despite just 0.15 in. of June rainfall for herbicide activation — with one exception. “One field gave us fits, and that was a field where we deviated from the plan.”

About a month after planting, the field looked clean enough to skip the postemerge application, “but that wasn’t the case.” By the time Steinkamp realized his mistake, “the Palmer was knee-high” — much too big to kill with any herbicide. So out came the hoes again.

Postemerge herbicides work best when Palmer plants are no more than 3 inches tall, Sprague says. That makes application timing a challenge, because the weed grows so fast. In 2012, Palmer amaranth in Sprague’s research plots “grew from 3 to 7 inches in fewer than 5 days.”

The good news is that “in the Midwest, we can control Palmer amaranth in soybeans and corn with the herbicides we have available today,” Steinkamp says — “as long as we have a good plan and stick to it.”

A game changer for Midwest farmers?

What makes Palmer amaranth so competitive, even in the Midwest, far north of its historic range?

Very rapid growth — 1 inch or more per day in ideal weather, a very long germination period, prolific seed production, and genetic diversity, which favors rapid adaptation and development of herbicide resistance, says Aaron Hager, University of Illinois weed scientist. The tiny seeds spread easily, too.

Upper Midwest scientists are studying the weed’s germination and growth patterns in northern environments. However, Palmer amaranth “appears to be just as aggressive here as in the South,” says Travis Legleiter, Purdue University weed specialist.

“Farmers had better take this one seriously,” Hager adds. “Those who don’t will find out the hard way that it’s very capable of significantly reducing corn and soybean yields.” Unchecked, Palmer pigweeds can slash yields by 11% – 91% in corn and 17% - 79% in soybeans, says Legleiter, citing research from Colorado, Georgia and Tennessee.

For more photos and scouting guides, go to: http://bit.ly/PalmerID.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like