January 15, 2016

Roger Hargrafen knows what it takes to defeat Palmer amaranth: zero weed seeds.

The aggressive pigweed is rapidly moving into the Midwest. Hargrafen, who raises corn, soybeans and cattle near Muscatine, Iowa, discovered the weed on his farm in fall 2013. By managing intensively, he has prevented Palmer amaranth seed deposits for two years.

| Download a pigweed infographic in .PDF format |

“This is very encouraging,” says Iowa State University field agronomist Meaghan Anderson. It shows that “with early discovery and good management, eradication may be possible.”

Hargrafen first found Palmer amaranth growing in a non-cropped area of a rented farm. “We don’t know for sure how it came in,” he says. The site has hog confinement barns, so the tiny pigweed seeds may have hitched a ride with feed or livestock. He believes it was present for about a year before he noticed it.

When Hargrafen checked his adjacent soybean field, he found the weed had spread to some end rows. “I felt the bracts and they were sharp.” Iowa State University Extension confirmed Palmer amaranth. Immediately, Hargrafen walked the entire perimeter of the 80-acre irrigated soybean field and found about 200 more Palmer plants.

100,000+ seeds/plant

That may not sound like a big deal, but Palmer amaranth — like its cousin, waterhemp — is a prolific seed-maker. A single female Palmer plant in competition with a crop can produce 100,000 seeds or more, Anderson says. “I call it waterhemp’s big, bad brother,” because of its rapid growth, prodigious reproduction, and potential to hammer yields.

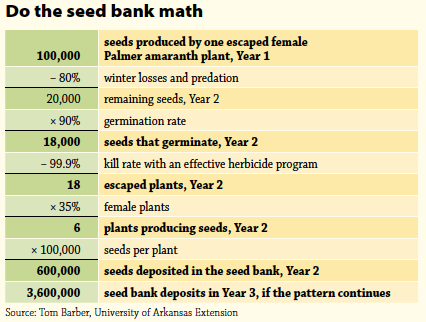

One escaped female Palmer amaranth plant, in competition with a crop, can conservatively produce 100,000 seeds, says Tom Barber, University of Arkansas Extension weed scientist. Following winter losses and predation, about 18,000 seeds will germinate the next season. If your herbicide program kills 99.9% of Palmer plants, you can expect 18 escapes. If six of those plants are females that each produce 100,000 seeds, you will add 600,000 Palmer pigweed seeds to the seed bank. If the pattern continues, seed deposits in Year 3 will exceed 3 million.

Fortunately, the pigweeds were confined to a four-acre section of Hargrafen’s field. On high alert, he walked ten adjacent acres of beans, finding two more plants, which he pulled and burned.

Hargrafen wanted to avoid spreading Palmer seeds across the field with his combine that fall, so he mowed the 4-acre patch of infested soybeans. Because the Palmer plants had emerged late in the season and were still bright green, he assumed their seeds would not yet be mature.

That assumption proved costly.

Some plants “had produced viable seeds, and I’m still trying to manage that seed bank now.” In hindsight, he wishes he had hand-pulled all the Palmer plants he could find before mowing.

| Download this article in .PDF format |

Removing crop acres

The next spring, Hargrafen took those 4 acres out of production, plus another 4 acres as a buffer.

Although he’s a longtime no-tiller, he started the attack by disking the sandy field to kill emerged weeds. He sprayed three times during the season, targeting the Palmer with overlapping residual herbicides and multiple modes of action in each pass.

In May, he applied Bicep II Magnum (Site of Action Groups 15, 5) at full rates, gaining about four weeks of control.

In early June, he sprayed a tank mix of Roundup plus 1.5 pt./acre of metolachlor (Dual) and 2.5 oz./acre of Status (SOA 9, 15, 19, 4). Fortunately, Hargrafen says, the Palmer population in his field is still susceptible to glyphosate. However, like most populations across the country, it is resistant to ALS inhibitors such as Classic and Pursuit. Many Palmer populations are also resistant to glyphosate, as well as atrazine and HPPD-inhibitors such as Callisto and Laudis.

Hargrafen planted a cover crop of sorghum and sudangrass the first week of July to shade out later-emerging Palmer plants, using a thick seeding rate of 50 lbs./acre. The first week of August, when the cover crop was about 6 inches high, he made a final herbicide application of 1.5 pt./acre of metolachlor plus 5 oz./acre of Status (SOA 15, 19, 4).

“Between the competition with the sorghum-sudangrass and the late POST, the field stayed clear the rest of the year.”

Hargrafen also sprayed adjacent non-cropped areas, including a CRP field, a key part of his zero seed production goal. “Palmer in non-cropped areas, where it was in competition with grasses and other weeds, didn’t get very high,” he says — maybe 12” to 18” tall, making it harder to spot than in a row-crop field.

He also paid close attention to the rest of the field outside the fallow section, where he’d found the two Palmer plants the previous fall. “I walked 15 acres of corn, scouting three rows at a time, but I didn’t see any more.”

All these efforts paid off: “I never found any Palmer amaranth plants that went to seed. That was my objective.”

| Download a pigweed infographic in .PDF format |

Cover crops help

In 2015, Hargrafen intended to follow the same plan, but time got away from him, and he didn’t get the cover crop planted. “That was a mistake.”

He was forced to take out late-emerging Palmer plants with tillage in order to prevent seed formation.

“You get a flush every three weeks. I disked the field four extra times.” Even so, one female plant survived three separate tillage passes and grew to maturity. Luckily, it was never pollinated, but it shows the level of vigilance that’s needed, Hargrafen says. “All it takes is one plant and you lose everything you’ve gained.”

Those later Palmer flushes grew about eight inches tall in three weeks, he says, and by then, “they’d be putting on a seed head.” University of Arkansas research found that Palmer seed heads as young as 14 days old may have viable seed and are capable of replenishing the soil seed bank.

After each disking operation, Hargrafen washed his equipment to avoid spreading Palmer seeds to new areas. “A cover crop would have saved me a lot of work!”

Did erosion spread Palmer?

Hargrafen prevented new deposits of Palmer amaranth seeds for a second season, but all the tillage caused erosion. Now, he’s concerned that Palmer seeds may have moved with the sediment to another area of the field. So in 2016, he will take 12 more rows out of production as a precaution. That’s tough to swallow, he says. “You look at how much money you are losing by doing that.” But he sees it as his best chance to eradicate Palmer and avoid having to manage the weed permanently.

To stem further erosion on the fallowed acres, Hargrafen planted a cover crop of cereal rye this fall. Next spring, he plans to plant bin corn in May as a cover crop, seeding at about two bushels per acre. “That’s my cheapest option for a cover crop.”

| Download a pigweed infographic in .PDF format |

Eradication

Aiming for eradication

Hargrafen figures if he can prevent new Palmer amaranth seed deposits for four or five seasons, he’ll have the weed pretty much licked in his 80-acre field.

Arkansas research confirms that, finding that about 90% of Palmer amaranth seeds germinate during the first two seasons. “Our research indicates that the Palmer amaranth seed bank will be almost completely depleted in four years if no additional seeds are allowed to enter,” says Tom Barber, University of Arkansas Extension weed scientist.

Arkansas farmers have been fighting Palmer amaranth for many years. Barber’s advice to Midwest growers who are seeing the weed for the first time: “Get on top of it. If you don’t maintain control early, you won’t even be able to cut a crop.”

Hargrafen seconds that: “The earlier you catch it, the better. Be aggressive in your management.”

Is eradication practical?

Can you eliminate a new infestation of Palmer amaranth from a field?

“It depends on the size and how long it’s been there,” says Meaghan Anderson, Iowa State University field agronomist. It also depends on how the weed seeds arrive. “If you can’t control the inflow, you can’t eradicate it.”

“We’d love to see complete eradication,” adds Bob Hartzler, Iowa State University weed scientist, “but that’s not simple.” Although Palmer amaranth is relatively short-lived in the soil, the sheer number of seeds produced makes eradication unlikely, says Tom Barber, a weed scientist in Arkansas, where growers have been battling the pest for years.

The good news is that control strategies are the same for waterhemp, a familiar Midwest foe, and Palmer amaranth, Hartzler says. “If you’re doing a good job with waterhemp, you’ll do a good job with Palmer amaranth.”

| Download a pigweed infographic in .PDF format |

Palmer amaranth still adapting to northern environments

Palmer amaranth, a Southwest desert native, has not yet fully adapted to Iowa and other parts of the northern Corn Belt, says Bob Hartzler, Iowa State University weed scientist. Although he has no hard data to confirm this, “it’s what I’ve observed.”

In Iowa, for example, Palmer pigweed seeds continue to germinate as long as the soil is warm enough — even into September — depleting the seed bank when there’s no chance for the plant to complete its life cycle. “Waterhemp doesn’t do that,” Hartzler says. “It’s smart enough to know when fall is coming.”

Likewise, the weed is showing up mainly on poor-quality soils in Iowa, another sign that it hasn’t fully adapted to northern row-crop environments, Hartzler says. “We have yet to find it on prime Iowa soils.”

Eventually, though, Palmer amaranth will adapt to the Midwest, he says. “That’s why it’s so important to attack it now. In ten years, it will be much harder to manage.”

| Download a pigweed infographic in .PDF format |

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like