Every penny matters in today’s commodity price cycle. So for farmers on the fence on whether to make the plunge for cover crops, take comfort: economics are now on your side.

Nevada, Iowa, farmer Scott Henry is one of a growing number of farmers who have the data to back up the notion that cover crops do indeed pencil out.

“Cover crops provide real long-term value, but they’re expensive,” Henry says. “To make the economics work, we measure returns across multiple years and reduce seeding and application costs as much as possible.”

Related: Study examines ag retailer challenges with cover crops

Henry’s family-owned operation, LongView Farms, manages 4,600 acres of corn, soybeans and sorghum with precision practices designed to squeeze efficiency from every drop of fuel and crop input. Henry incorporates no-till practices where applicable and has tested several cover crop cocktails to see which work best — and cheapest — on his land.

Do cover crops pay? Henry thinks so, and to prove his theory, he and other farmers shared their farms’ finance records with K·Coe Isom AgKnowledge and the Environmental Defense Fund. The groups used the data to generate a report, “Farm Finance and Conservation: How stewardship generates value for farmers, lenders, insurers and landowners.”

Related: Explore 3 conservation case studies

Start by controlling costs

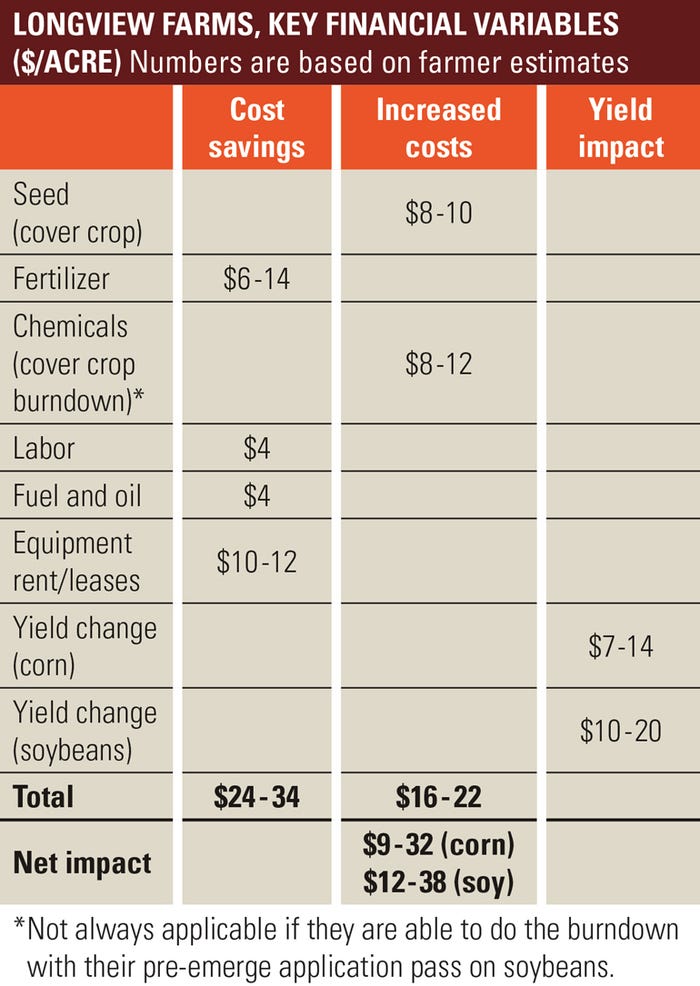

To figure cover crop profitability, start with upfront costs. LongView Farm uses a mix of oats and rye, which costs less than many other cover crop options. Henry’s target for cover crop seed cost is $8 to $10 per acre. Terminating the cover crop with herbicides costs an additional $8 to $12 per acre.

The tricky part of this debate is determining non-tangible savings and converting those to dollars. Henry believes the initial increase in the farm’s seed cost is offset by better nitrogen efficacy from the covers, and that leads to reduced fertilizer costs. In addition, two years ago Henry’s farm experienced drought, but fields with cover crops had higher water retention, which boosted yields.

Cover crops also offered better weed control on some acres — even better than herbicides. Scott estimates this correlates to a yield increase of 1 to 2 bushels per acre in soybeans for increased revenue of $10 to $20 per acre, and a yield increase of 2 to 4 bushels per acre in corn for an increased revenue of $7 to $14 per acre.

Operational costs also see savings with no-till or minimum tillage. “We’re seeing less labor, less fuel and other expenses on equipment,” he adds.

In the end, he’s able to see a net benefit in his pocketbook, as well as longer-term yield resilience for production coming off those acres.

Henry prioritizes collecting data, as well as tracking and understanding the growing process. “We believe that the greater insights into our operation provided by new data and monitoring technologies will help unlock further advantages for our farm and the environment,” he says.

What works best for you

Of course, what works for one may not work for another. That’s why Josh Yoder began testing cover mixes first in field trials.

“We discovered that no-till production helped improve our soil structure year over year,” says Yoder, who farms 1,800 acres with his father, Fred, in Plain City, Ohio. “With the addition of cover crops, those benefits seem to be accelerating fairly significantly. We still have a bit to figure out but feel that we are on the right track.”

The Yoders started experimenting with cover crops by planting a three-way mix of tillage radish, winter pea and crimson clover behind wheat in mid-August to get enough growth before first frost. They saw a 2.5-bushel-yield boost in soybeans the following year. However, the cost of seed was $35 per acre, and application cost was $10 to $12 per acre.

Josh decided to take wheat out of their crop rotation and made the switch to a cereal rye cover crop that could be planted behind harvested soybeans, as well as behind corn. He plants the rye directly after the combine is out of the field and allows it to grow through spring until it reaches 12 to 18 inches in height. He applies glyphosate as burndown in April before spring planting.

“Burning down the cover crop at this stage allows the planter to get through the field efficiently and preempts the growth of pests, such as army worms and slugs, that could damage the following crop,” Yoder says.

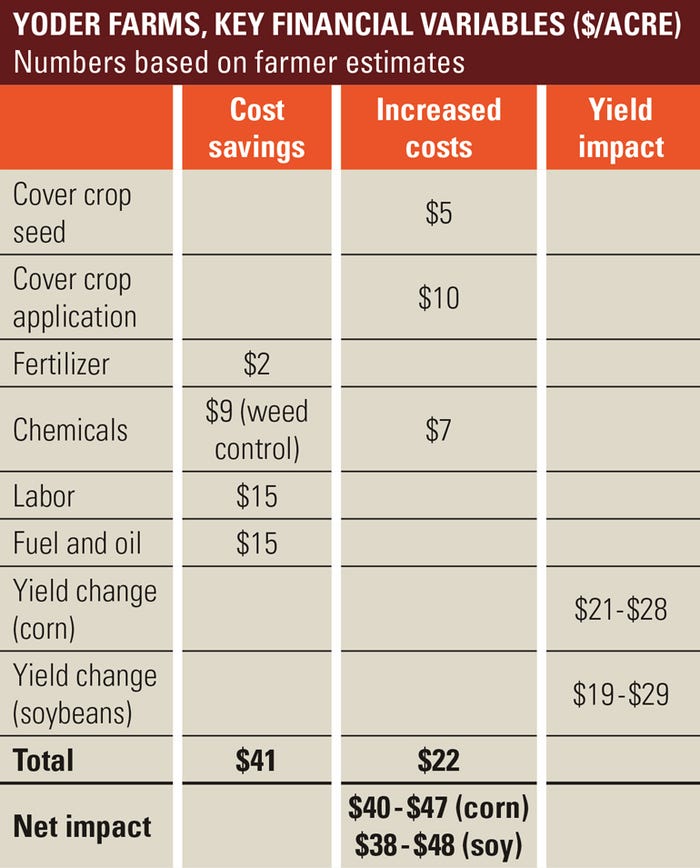

The rye cover mix offers lower seed costs compared to his first attempt at cover crops. He spends per acre $5 in seed, $10 in application costs and $7 for burndown, essentially cutting his costs in half from his original cover crop regimen.

He estimates he is saving $9 per acre in weed control. He also estimates 6- to 8-bushel yield gains for corn and 2- to 3-bushel gains for soybeans, resulting in an increase in revenue of $21 to $28 per acre for corn and $19 to $29 per acre for soybeans.

Overall, his cost savings and yield boosts provide a $40- to $47-per-acre benefit for corn and a $38- to $48-per-acre revenue increase for soy, significantly surpassing his $22-per-acre cost of the rye cover crop program.

Partner with landowners

Cover crops can also enhance the relationship between farmer and landowner.

“We’ve begun to see language written in leases about record keeping and reporting back to the landowner about what management practices we are using,” Henry says. That opens a dialogue on how those practices improve the landowners’ farm. It may result in a conversation on how landowners can be incentivized to participate in the cost of land improvements.

“If we can use the data to show there is a positive impact of using cover crops, potentially we can add an addendum that results in a minor reduction in rent,” Henry says.

Public-sector programs ignited tremendous progress in cover crop adoption. In Maryland, the state government funds a robust cover crop incentive program that pays farmers up to $75 per acre to cover costs.

Also, a new focus is now coming from the private sector. Peoples Co., a leading provider of land brokerage, management, investment and appraisal services in 20 states, partnered with Stine Seed, the largest independent corn and soybean seed company, to offer landowners a paid-in-full, managed cover crops program starting in 2019.

The program, called the Sustainability Cover Crop Initiative, will be available to landowners in Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Nebraska and Missouri for a three-year term. To receive cover crops paid in full by the program — a value of up to $30 per acre — landowners must agree to have their land professionally managed by Peoples Co. during the three-year term and commit to planting Stine Seed.

The program is available for new land management accounts with Peoples Co., up to a maximum of 10,000 acres. Cover crop application costs will be covered up to $30 per acre, with a minimum of 120 acres and a maximum of 500 acres planted per client. Cover crop seed and application decisions will be made by land management professionals.

Peoples Co. President Steve Bruere says, “I’ve always believed that since a significant amount of land is rented, an effective strategy to reduce environmental impact and maximize yields should be targeted at landowners. Our program will show landowners it’s possible to reduce environmental impact while increasing productivity.”

Marathon, not a sprint

Alan Grafton, director of K·Coe Isom AgKnowledge, says their findings confirm that farmers were able to lower costs and increase revenues in many different areas. But it’s also important to realize there’s no silver bullet.

“As growers look to adopt these practices, the great thing about this is it isn’t a wholesale change that has to happen all at once,” he says. “It is important to measure the outcome in order to test the viability of the practices.

“This is not a short-term play, this is about the future. It’s a marathon, not a sprint.”

Related: 4 tips for successful cover crops

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like