August 24, 2015

It’s bad enough that farmers have little or no control over production due to weather (pests and diseases we can attempt to control/manage), but farmers also have no control over prices—the price “level." The price “level” is determined by global supply and demand.

Farmers can, however, exercise some control over the variability in price around the price level. If, for example, supply and demand determine that cotton should be 65 cents per pound, farmers might be able to make decisions that would help them average better than 65 cents. But this is where the frustration comes in—how to do that, when to make pricing decisions, and how to evaluate alternatives.

Profit depends on price, yield, and cost (Profit or Net Return = Price x Yield - Costs). To keep costs under control, every input and every production decision should be evaluated closely. Farmers do a very good job in this regard and university research and Extension recommendations are focused on improving yield and/or reducing the cost per unit of production—not per acre but per pound of lint in the case of cotton. Yields, of course, are largely determined by the weather unless irrigated but farmers also have to do things in the right combination and at the right time to optimize yield potential. Again, farmers do a very good job with this.

But marketing and making pricing decisions can be frustrating. Why is that? A farmer can work all season long to make a good yield and control costs while making a good yield, but then lose profit potential due to pricing and marketing.

The first key in making marketing decisions is to know your cost of production. This tells you how much risk you can withstand. If your variable cost of production is 60 cents per pound and the market is at 70 cents, you’ve got a 10-cent cushion. If the market goes down to 65 cents, you have dug a hole but not as deep a hole compared to someone whose cost was 65 or 70 cents. It’s all about risk. Marketing is not necessarily about getting the high price for your crop; it’s about getting a good price and making a profit while also managing risk—not risking losing 10 cents just to make another 2 cents.

The risk vs. price balancing act

So, it’s possible that farmers will make a different decision based on their respective cost of production and how much risk they are or are not willing or able to take. Somehow you have to find a balance between price and risk and know when the odds are in your favor—pricing the crop or a portion of the crop when the odds of price going down are much greater than the odds of price going higher.

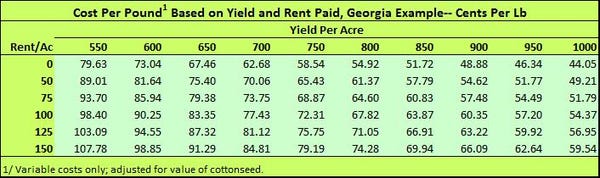

The following table illustrates the variable cost per pound of lint at varying yield levels and varying amount of cash rent per acre. Based on where the market is at or expected to be, it clearly shows which combinations are feasible and which are not. This is a Georgia non-irrigated example, but it shows that at an 800-lb yield and $100 per acre rent, the variable cost per pound is 68 cents—barely breakeven at this year’s prices. Depending on your cost of production, marketing decisions should be consistent with your ability to withstand the risk of prices going below your cost.

Cotton growers have at least 18 months to make pricing decisions. I like to break decisions down into 2 periods—pre-harvest and post-harvest. Pre-harvest, the main concern is prices (Dec futures) going down. Your choices include do nothing, fixed price contract, basis contract, equity contract, minimum price contract, and Put Options. You have to balance your need for protection with the realization that prices could go up rather than down.

Post-harvest, you have uncommitted crop and must consider selling it or holding for possibly higher prices later on. Your choices include sell at harvest, deferred price contract, store and sell later, store in Loan, and Call Options. If prices go up as you hope they will, any of these latter four will potentially make money. Instead, if prices are flat or go down, they are not all equal. Post-harvest you have to carefully evaluate the potential for the market to improve then, if you want to defer pricing, make decisions that will not risk everything you have already worked so hard to achieve.

(Don Shurley is Professor Emeritus of Cotton Economics,Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics University of Georgia ([email protected]))

You May Also Like