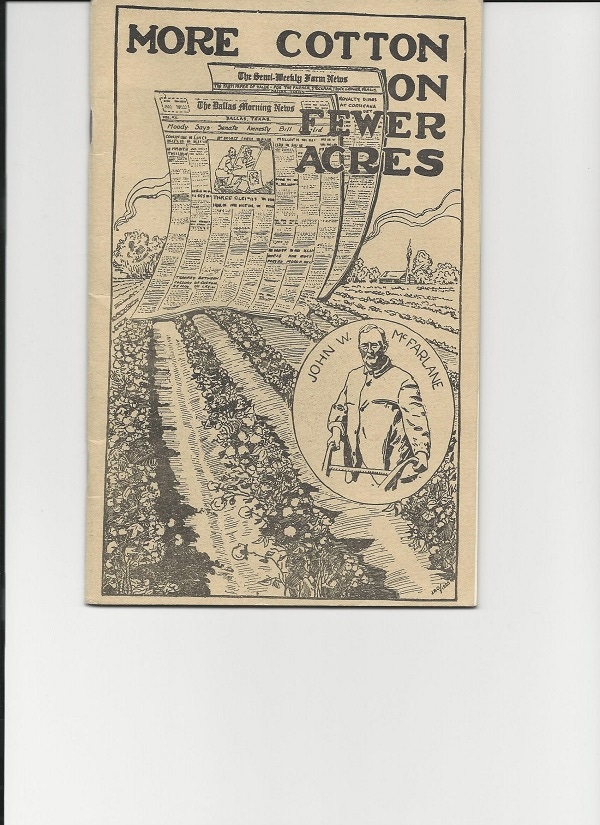

Anderson County, Texas, farmer John McFarlane made better than two bales of cotton per acre, dryland, and with no rain from the end of May until September.

In addition to the profit from his cotton crop, McFarlane picked up an additional $1,000 in prize money as winner of the Texas Cotton Contest.

Averaging two bales of dryland cotton per acre with so little rainfall marks an outstanding achievement and shows better than average management. That accomplishment stands out even more considering that McFarlane made this crop in 1924, when the average Texas cotton yield stood at 141 pounds of lint per acre.

The contest, dubbed “More Cotton on Fewer Acres,” by sponsors The Dallas Morning News and its semi-weekly publication Farm News, with cooperation from the “Extension Service of Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College,” began as a means of encouraging better management for cotton farms.

“Cotton is the keystone of Texas agriculture,” according to a brochure published to announce winners, production practices used to reach winning yields and to establish requirements for the contest to continue into 1925.

If you are enjoying reading this article, please check out Southwest Farm Press Daily and receive the latest news right to your inbox.

Former Southwest Farm Press editor Calvin Pigg loaned Farm Press a copy of that publication, which offers insight into the important role cotton has played and continues to play in the Texas economy. The publication also noted: “Texas is the greatest cotton-producing State in the world and in recent years produced annually about one-third of all the cotton grown in the United States.

“In the face of serious threats of extensive cotton-raising in foreign countries, chiefly British dependencies and Brazil, Texas can hold its world supremacy as a cotton producing State only by adopting a practicable program of soil improvement leading to increased cotton yields per acre.”

With a few minor edits, those statements could apply to Texas cotton today.

But further comments show how support for agriculture has declined, especially in urban centers. “The decline of acre yields of cotton in Texas during recent years is of great concern to every business man (sic), banker and farmer in the State since cotton is generally recognized to be the barometer of business conditions.”

Yield averages

A table showing yield averages from 1921 through 1924 proved the need to take action. Average yield in 1921 was 98 pounds per acre—from more than 10 million acres. In 1922, average yield was 130 pounds from more than 11 million acres. In 1923, Texas farmers planted more than 14 million acres in cotton and averaged 146 pounds per acre. And in 1924, farmers made 141 pounds per acre on more than 16.5 million acres.

Reasons for the yield decline included dependence on a monoculture of cotton that depleted soils. According to the brochure: “… it has been the history of all countries whose agriculture is devoted largely to a one-crop system, such as cotton, to reach a condition where farming practices must be changed to re-establish a balance and enable crop production to be profitable. Where this has not been done the result is disaster.”

The contest and a proposed four-year program to identify and incorporate better management practices for cotton production also sought to make Texas farms more self-reliant. By increasing per acre yield, organizers said, farmers could divert more acreage to livestock, grains, fruits, and vegetables. The ultimate goal was to use cotton as the cash crop and let other acreage provide for the family’s needs instead of using cotton profits to purchase milk, eggs, and other necessities.

Organizers also realized that production practices for a state as large as Texas could not be uniform and that “practices which are adapted to East Texas conditions are not applicable to any great extent to the black prairie land region of North and Central Texas, which is considered the most important cotton-growing section of Texas and which, in the opinion of many students of cotton, is held to have suffered seriously from soil depletion through continued one-cropping.”

The program sought to collect information from the cotton growers who entered the contest. “Each entrant in the Cotton Contest agrees to keep a Crop Record throughout the season in which he will record every operation performed on his five acres (the required acreage) of cotton as well as on the rest of his land planted to cotton.”

The assumption was that with better management farmers could raise as much cotton on five acres as they previously did on 10 or more, leaving land available for other crops and increased self-sufficiency.

It’s also interesting to note the practices employed by the winning farmer, some of which are long outdated, but some that remain viable options today.

The pamphlet showed that McFarlane picked good land for his contest plot, five acres of sandy loam bottom. His cotton followed a ribbon cane crop from the previous year.

He “flat-broke” the land with a breaking plow, “requiring fifty hours of a man and a team.” More cultivation followed, including: a section harrow and bedding with a “middle buster.” He applied 400 pounds of a 10-3-3 commercial fertilizer “in the water furrows, mixed and bedded back with a breaking plow, requiring two days.”

He planted one bushel of seed per acre behind a “walking planter.” Seed cost was $2 a bushel. Spacing was four feet between rows.

He started cultivating with a “Georgia stock” and sixteen-inch sweep—15 hours. He devoted 15 hours to chopping cotton to “a stand of one, two, three and four stalks to a hill and distance between hills twelve to sixteen inches. Fifty hours were devoted to chopping.”

He cultivated with various sweeps a total of ten times during the season, along with two hoeings, and a total of 361 man hours—“seventy-two hours per acre.”

That’s for five acres of cotton. Herbicides have made that chore significantly easier.

Profitable crop

It was a good crop, however. McFarlane made a profit. Total production cost was $301.12, including 12 cents per hour for labor, 10 cents per hour for horse or team hours. Fertilizer cost was $48.75. Picking cost, $1 per hundred pounds, $122.75. Ginning cost was $63.50.

Profit was $193 per acre with cotton bringing 23 cents a pound. That includes a $100 value for cottonseed.

One reason organizers offered for McFarlane’s success was that he had always been a diversified farmer. “Mr. McFarlane has followed diversified farming ever since he made up his mind to take over his mother’s farm and manage it,” according to the contest brochure.

Farm acreage totaled 300 but he planted only 90 acres in cotton. He also raised and sold vegetables, watermelons, fruit, chickens, dairy products and hogs.

“The McFarlanes produce practically all those things on a farm which insure a good living,” contest organizers said.

McFarlane himself, in an article he authored, wrote about his commitment to conservation. “There are some things I insist on being done, and to my mind are necessary for a maximum production of cotton.”

He said low land should be drained and all upland should be terraced “so as to prevent washing.”

He insisted on a “good solid seed bed,” and that the cotton “should be cultivated rapidly.” He recommended weekly cultivation. Weeds, then and now, rob nutrients and moisture from cotton plants.

He also advised all farmers to check with experts and “consult with their county agents until they have considerable experience in producing more cotton per acre. There is one thing I want to say to my fellow-farmers, which is that the good Lord and fertilizer are not going to make a cotton crop.”

Contest participants beat averages

McFarlane was not the only contest entrant to increase yields significantly. According to contest directors: “While the average yield of lint cotton in Texas for the last five years is around 130 pounds an acre or slightly more than one-fourth of a bale, the average yield for the eighty-six highest entrants in the ‘More Cotton on Fewer Acres’ contest is almost 400 pounds an acre for each five-acre contest tract, or more than three times the State average.

“Also, the high men in the cotton contest produced their cotton from 7 (cents) to 10 (cents) a pound instead of 20 (cents) to 25 (cents) as has been held to be the average.”

Texas AgriLife Extension state cotton specialist Gaylon Morgan says the cotton contest may have had a long-term effect on Texas cotton production.

“The whole purpose of the high yield contest was to educate fellow producers about management practices that would improve yields,” he says. “In many ways, the educational effort of the yield contest was successful. Our yields are higher, and we are growing cotton on 50 percent fewer acres than in the 1920s.”

Morgan says farmers still listen to other successful farmers to pick up ideas. “Although less emphasis is on farmer-to-farmer education today, farmers still prefer to hear input from their farming colleagues than any other source. For example, at Extension meetings, the farmer panels are always the most popular portion of the program.”

Morgan also praises McFarlane’s documentation of production inputs, especially for labor costs.

“To think how much our crop production efficiency has increased over the past 90 years. We have replaced man and animal labor with tractors for tillage, harvesters, and weed management. This process has substantially increased efficiency (pounds of lint per acre) and pushed farmers to make their income by farming more acres.

Dryland costs still similar

“It is interesting that total input costs were fairly comparable to today’s input cost for dryland cotton production. Fertilizer was and continues to be a major production cost. However, in the 1920s, the majority of the input cost was in labor, and now it is in machinery and crop protection products and technology. The very quick adoption of the John Deere round bale module picker is a prime example of adoption of machinery to increase efficiency and decrease labor costs.”

Morgan expressed surprise that pest management was not an issue. “I was surprised not to see any mention of the boll weevil. The boll weevil had progressed through most of East Texas by the early 1900s and had a major impact on yields.”

Much has changed in cotton production since 1924. It’s been many years since farmers relied on horses or mules to work their acreage. It’s been a long time since seed cost as little as $2 a bushel, labor was 12 cents an hour, fertilizer cost was as low as $48 or cotton prices as low as 23 cents a pound.

But some common denominators remain. It still makes sense to control weeds as quickly as possible or they will, as a Texas AgriLife (a new moniker, too) weed science specialist says, “pick your pocket.” But cultivating 10 times is out of the question, though some farmers may be reverting to “cold steel” as a remedy for herbicide resistance weeds.

Many still use hoe hands, when they can find them and if they can afford them, to chop weeds.

Conservation still makes environmental and economic sense. Erosion prevention has added new tools—cover crops, reduced tillage, and sand fighting, for instance—but terracing still plays a role and assuring proper drainage is as important as ever.

Crop rotation may not be used as much as it should be, certainly not to the extent that John McFarlane alternated crops. Few Texas farms today are as diversified as McFarlane’s. But many cotton farmers are looking at better ways to use land—split pivots with half in cotton and half in a crop that uses less water or uses it at a different time.

Higher grain prices in recent years have offered better rotation options and technology, as Morgan says, has improved efficiency.

And farmers continue to learn from other farmers. The Farm Press High Cotton Award, for example, though not a yield contest, selects farmers who demonstrate high levels of stewardship and conservation standards to produce efficient and profitable cotton crops.

John McFarlane would have been a good candidate for the annual High Cotton Award.

Also of interest:

Rotation, variety selection, timeliness are critical for SW high cotton…

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like