The fundamental approach to forecasting commodity prices boils down to whether the leftovers from tonight’s supper are bigger than last night’s leftovers. For row crops, we make this comparison annually, and we call the leftovers “Ending Stocks” or “Carryover Stocks”.

Ending stocks are what’s leftover at the end of the marketing year, after you reduce your total supply (carry-in, production, and imports) by domestic use and exports.

The most basic way to forecast cottons prices starts with making an educated guess about the size of next season’s cotton ending stocks (or wait for USDA to do it). Then if your guestimate of next season’s ending stocks is at least a million bales higher than the previous seasons, that suggests weaker prices than during the previous season.

Likewise, a significant decrease in next season��’s cotton ending stocks should result in stronger prices, year-over-year. This forecasting is commonly done on an ad hoc, “from the gut” basis. It can also involve fancier statistical models, but the logic is the same. The expected change in price levels, year-over-year, is in the opposite direction of the year-over-year change in ending stocks.

In addition to forecasting next season’s price levels, the year-over-year change in ending stocks is also associated with different seasonal pattern of prices.

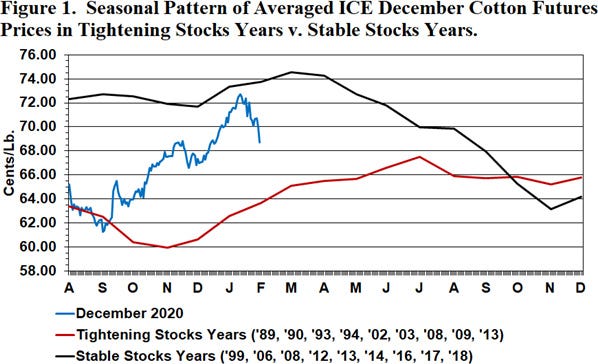

Figure 1 shows two seasonal patterns of cotton prices. The black line shows the average of historical December cotton futures prices in years when the ending stocks was within a million bales of the previous season’s. The pattern shows the normal seasonal highs during planting season, as well as the familiar harvest-time price pressure. If we extrapolate this pattern to the current level of Dec' 20 futures, we might expect prices to trade to the mid-70s in the spring, but slide into the 60s by harvest time.

On the other hand, in years when the ending stocks are at least a million bales lower than the preceding season (the red line in Figure 1), the pattern is different. The spring price rally stretches into the early summer. And there is more support for prices later in the year. Superimposing this pattern onto Dec' 20 futures also suggests that prices may rise above the mid-70s, but maybe they’ll hang in there above 70 cents.

Which outcome will we see in 2020? There are too many moving parts to know with certainty, including planted acres, abandonment, crop condition, yield, etc. But at least we can be ready for the scheduled benchmarks, including:

1. The National Cotton Council’s planted acreage survey results

2. USDA’s March 31 Prospective Plantings

3. USDA’s May WASDE U.S. balance sheet projection

4. USDA’s June 30 Planted Acreage report

5. August and September U.S. production forecasts.

For additional thoughts on these and other cotton marketing topics, please visit my weekly on-line newsletter at http://agrilife.org/cottonmarketing/.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like