It sounds odd but at the same time a bloated Mississippi River was flooding part of George Lacour’s cotton acreage, another portion of his Louisiana cotton was drought-stricken. Months after the season had ended, the Southern Cotton Ginners Association (SCGA) president was still coming to terms with the 2011 growing season.

“It seems a lifetime ago -- so much happened,” said Lacour. “I told someone ‘We went home on Good Friday. We had the tiger by the tail and the world was going great. Then, the next Monday morning after it had rained so much in northeast Arkansas and southeast Missouri, everything had gone to hell – and it went to hell quick.’”

Early-planted cotton was lost to floodwaters. “I lost a couple of thousand acres overnight. At the same time, believe it or not, the outside areas of our land were experiencing drought.”

There was hardly time to despair because “there was still another 3,000 acres we were in the middle of trying to plant, harvest, and take care of.”

Facing multiple crises, every day raced by. “Most of May was a blur. We had to take things out of the (Morganza) floodway that we’d accumulated over the last 30 years. We dismantled fuel tanks and sheds and moving equipment. At the same time, we were trying to plant cotton and harvest wheat before the water took it.”

For comprehensive coverage of the 2011 floods, see here.

Lacour’s corn – mostly dryland -- had gotten off to a great start before drought set in. “We ended up making a decent crop, though – 150 bushel range – and sold it for a good price.

“That’s another thing that was going on: the commodity market was going bananas while the flood was occurring. Soybeans were at $13 and corn was at $7. Should you sell more? There was a lot of uncertainty.”

Lacour had a beautiful bean crop already up. He also had 100 acres of cotton emerged and sold for $1.30 per pound, “which we were ecstatic about. Then, we’re suddenly staring at floodwaters taking it under – that’s very humbling. You’re forced to live life one day at a time.”

Luckily, “we ended up with a pretty good cotton crop. This area averaged about 1.75-bale. The drought got some of it.”

Operation and varieties

Lacour farms outside Morganza, Louisiana, on two rivers in Point Coupee Parish: the Mississippi and the Atchafalaya. “It’s about eight miles between them and that’s the region we farm.”

Pinched between the two rivers, Lacour says he’s still trying to figure out where newer cotton varieties fit best on his land. “Our soils are mostly alluvial although we farm some heavy clay ground. For years, we planted 555, which was excellent in our clay dirt. It didn’t do as well on our lighter soils on the riverfronts – it would grow too tall. … 1133 and 1137 look like they will do well on heavier dirt. We like 5288 in sandier soils.”

Every Delta farmer has to go through the same discovery process. “That’s a challenge for the cotton industry. When you get a new variety, what will it do? And where will it do it best? What does well in Marianna, Arkansas, is not necessarily the best choice for Morganza. I’m a big proponent of test plots scattered all over the Mid-South because cotton is a unique creature.”

To help make decisions, “we��’ve done university and company trials over the last 16 years. The companies have become more reluctant to release their varieties – corn, beans or cotton -- to the universities. … I’m not sure of all the reasons but I’m glad to be able to offer land for them to try varieties here. It helps me figure out the best options.”

In Louisiana, “we spend money promoting 15 to 20 on-farm variety trials scattered around the state. We only have 290,000 cotton acres here. That’s a lot of plots and we used to not back those. But we’re out seeking the new variety leaders. Now, moving into 2012, we have a much better handle on it. Coming into 2010, though, we had much less understanding.

“What hurts is … a variety that proves to be a disaster. You can’t stand that in this day and age. You can’t come back from that. With all the financial pressures now, it isn’t about trying to make the top yield in the state; it’s about not being caught planting the dog.”

History

A fifth generation farmer, most of the land Lacour’s ancestors owned is now in the spillway. Back in the 1930s, his grandfather had to move out of the part of the spillway that flooded in 2011.

“He was with a cotton gin sitting on the river. In the late 1800s, they loaded boats with cotton that had just come out of the gin. Of course, in those days, we had a make-shift levee.”

Then, the boll weevil put folks out of the cotton business in the area. Soybeans became valuable “so we went for a long time – in the 1960s and 1970s -- without cotton.”

During cotton downturns in the Point Coupee area, “what saved us was the area never was 100 percent in the crop. So, when everyone else took big hits in the ginning and cotton industry, we were able to absorb the blow much easier. We’ve always been diversified here, doing the corn/cotton rotation since the 1980s.”

Soybeans still “compete mightily” with cotton in the area. “We may squeeze in 10,000 acres of cotton alongside 100,000 acres of beans in the region. Along with that, there are about 20,000 acres of sugarcane and, maybe, 25,000 acres of corn and 20,000 acres of rice.”

Going forward, “our biggest challenge in this parish is to find young farmers who want to grow cotton. With the price of other commodities, most young farmers would mostly rather take the easy way out and grow soybeans. It’s hard to blame them with the current price of beans.”

Along with his neighbor, Paul Roy, Lacour got back in the cotton business around 1987. The pair, without a place to gin, hauled cotton to the next parish.

Cotton came back when beans “fell out in the late 1980s. In 1989, we made a good cotton crop and in 1990, the parish’s cotton acreage really jumped. But we had cotton picked in late August that wasn’t ginned until Christmas Day. Obviously, we needed another gin.”

Tri-Parish Gin was built in 1991 about a quarter-mile from the river dock in the industrial park near Lettsworth, in the northern part of Point Coupee Parish. About a dozen growers came together with outside investors and “scraped together” enough money to build.

Due to the gin’s location, it’s worked well strategically. “We’re able to haul cotton out of three parishes within five miles.

“We will haul cotton a long way. Around 2000, we hauled cotton 80 miles. We’ve hauled cotton out of Mississippi. Generally, though, we’ll haul in about a 40-mile radius.”

SCGA

Lacour is proud of having been a member of the SCGA “since Day One in 1991. We believe in it. And one of the reasons we believe in it is we are big supporters of gin safety. SCGA has a safety program second to none. It is the top dog.”

There are plenty of benefits, but if for no other reason “we’d belong to SCGA for the safety watchdog aspect. Back in 1992, we had an accident with loading barge with seed during our second year in business. Some guys got hurt, unfortunately, and it cost us a lot of money.”

Any turnover in the ginning crew means new risk. “You can’t take for granted what they know. They may be unfamiliar with the exact piece of equipment they’ll operate. You have to make sure all those bases are covered for safety. So, we use meetings, instructional material, whatever.

“You can’t afford to be in business without insurance and without a good safety program you can’t have insurance.”

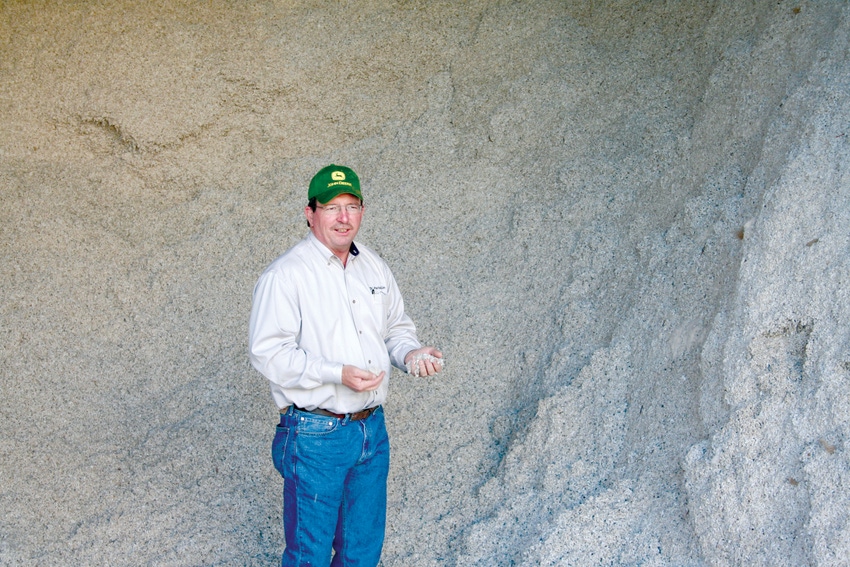

The sale of cottonseed is another reason Tri-Parish Gin is in good shape. “We have seed houses and can hold about 5,000 tons. We’re able to load cottonseed right out of the gin onto barges. The majority of our seed is barged to the north.

“Our ginning season is all over the place. We may start ginning at the end of August and we may start in early October. It’s not as regular as in other areas.”

Issues

There are numerous legislative and regulatory issues Lacour has opinions on, but two jump out: labor and environment.

“As for the environment, the biggest factor is dust. Gins are dusty and they’re situated in rural America, where dust is normal. … Too many environmental regulations will put us straight out of business. I’m not sure how you can possibly make a cotton gin dust-free. It’s (endemic to the business) and the countryside. Drive down the road and if it hasn’t just rained there will be a rooster tail of dust behind the pick-up.”

On the labor side, the onerous requirements regarding the hiring of a migrant workforce “are very difficult. The hurdles we jump to keep migrant labor are getting taller and taller.

“The E-Verify system really puts a burden on the employer. I’m just trying to find someone reliable, who will show up on time and is willing to work. I want to pay them a just wage. A good quality worker makes for a good safety program. But we can’t even get anyone to show up.”

And if the gin does find a migrant worker willing to sweat, “the government comes back and says ‘your documentation is faulty, the paperwork isn’t just right. He can’t work there.’

“I’m afraid it’s going to get worse in the Mid-South. You can’t just pick up a good press man off the street. Nowadays, if you find a good janitor, you’re lucky.”

On the new laws passed in the Southeast to deal with illegal aliens, Lacour doesn’t believe “the majority of people realize what agriculture is facing. They don’t realize the challenges facing those wanting to feed and clothe them. They don’t seem to believe that a few politicians are so naïve.

“What this has proved is it only takes a few people to stand up and complain and (the resulting legislation) doesn’t represent the majority. The squeaky wheel gets the grease. And without cotton ginners in the South, there wouldn’t be any grease.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like