The northern hemisphere is currently in a La Niña advisory, which means the cool Pacific waters that cause La Niña conditions are expected to continue with 95% probability during January-March, and then continue with 65% odds during March-May. By June things are forecasted to be back to normal. That means we’ll have a good ol’ hot Texas summer following what may be six months of exceptional drought in western Texas.

La Niña conditions imply warmer/drier weather in the Southern Plains region. This can have big impacts on cotton emergence, abandonment, and harvested yield. But not all La Niña winters are created equal. NOAA classifies the oceanic cooling effect as either weak, moderate or strong. � The current one is on the border between moderate-to-strong. Among the historically strong La Niña winters was the one preceding the record 2011 drought. A moderate La Niña preceded the 2012 drought. The droughts in 2006 and 2009 were associated with weak La Niña conditions.

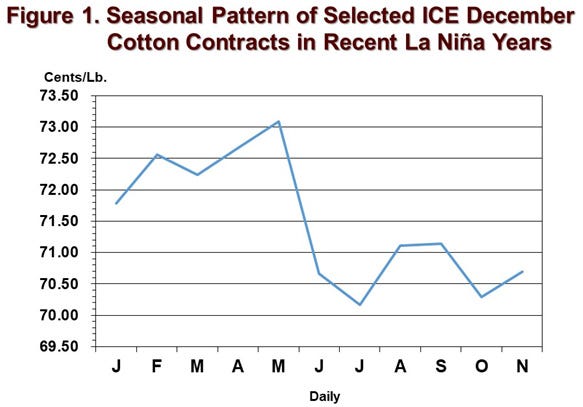

I was curious about the cotton market response to La Niña drought conditions. So, we gathered monthly average December cotton futures prices following all the La Niña winters going back to the 90s. We excluded 2008 and 2011 as outliers, and averaged the monthly average December futures prices across the other La Niña years to get the seasonal pattern shown in Figure 1.

What can we say about harvest-time cotton futures following La Niña winters? First, we can see that, on average, Dec futures prices rise through the end of planting time. I would assume that is associated with uncertainty about planting and emergence.

Going into the summer, the seasonal pattern of prices does a downshift, with up and down volatility around the benchmark USDA production reports in August and September. Again, I think this variability in prices at a lower level reflects the weakening of prices as the crop size gets more certain. That price weakening effect even happens during drought years. Once the uncertainty premium fades, the normal harvest-time price pressure appears to kick in.

Now, it should be noted that there is a lot of variability in the underlying annual price patterns. If I plotted the individual years, they would look like somebody spilled spaghetti across the dinner table. That’s because most years have unique influences. Demand conditions were different across those La Niña years. Relative crop prices and planted acreage were different, along with changing farm programs and different global influences.

What does that mean for the future pattern of December 2021 cotton futures during calendar 2021? It means, as always, that nothing is certain. Growers might at least be looking for pricing or hedging opportunities prior to May.

For additional thoughts on these and other cotton marketing topics, please visit my weekly on-line newsletter at http://agrilife.org/cottonmarketing/.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like