August 10, 2016

Bacterial blight has quietly found its way back into cotton fields for the second year in a row. There is little we can do about it now. However, by knowing more about this disease, cotton growers can make decisions to minimize impact next year and beyond.

Now in my 16th year as an Extension specialist at the University of Georgia, I have typically seen only light outbreaks of bacterial blight. This changed in 2015, when seemingly out of nowhere, bacterial blight caused significant premature defoliation and boll rot in a number of fields. The disease was found in more than one variety, but DPL 1454 B2RR, a promising variety with resistance to the southern root-knot nematode, was most severely affected. I was hopeful that the disease would go away if our growers planted varieties other than 1454 this season. Unfortunately, it is back.

Bacterial blight is caused by Xanthomonas citri pv malvacearum. The pathogen can survive in infected crop debris and can be seed-borne. However, acid-delinting cotton seed has been an important measure to minimize spread of the disease through contaminated seed. The bacterium enters the leaf tissue through natural openings, such as stomates and through wounds and injuries. The disease can be most severe when storms produce blowing rain and in irrigated fields. Our summer storms are often preceded by wind-blown sand that creates wounds more easily infected by the bacteria moved in the rain and rain-splash from infected leaves.

Symptoms of disease

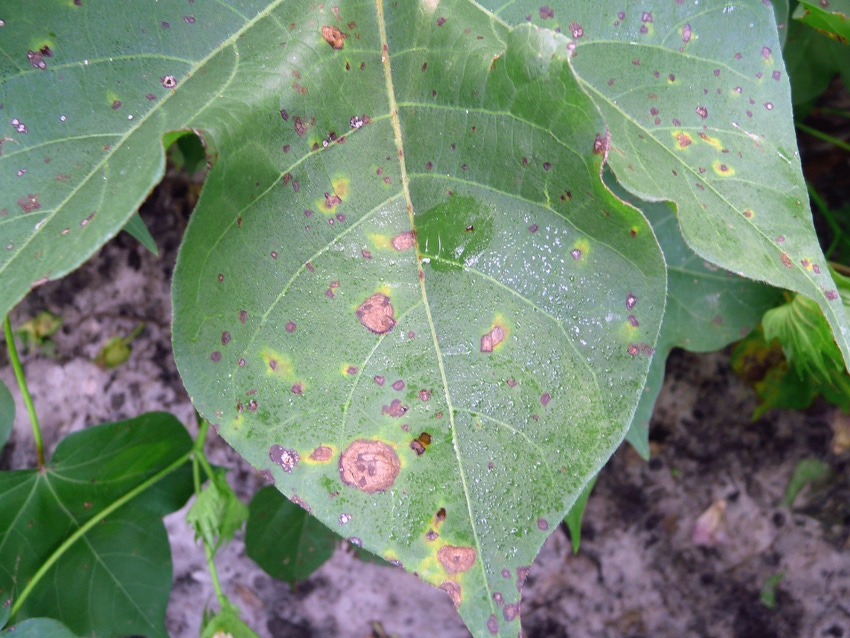

Because bacterial blight has been uncommon in the southeastern US, growers and consultants may be unfamiliar with the symptoms. Leaf spots are first observed as small, “water soaked” lesions best viewed from the underside of the leaf. With time, these water-soaked lesions become small necrotic spots characteristically delimited, or bound, by the veins in the leaf. This gives the spots an “angular” appearance; presence of water-soaked, angular spots makes diagnosis of bacterial blight relatively easy.

As the disease continues to develop, smaller spots coalesce into larger lesions, sometimes encircled by a yellow halo. The bacteria may enter the leaf veins and spread causing dark, “lightning bolt” streaks to appear. The bacteria can infect the bolls causing symptomatic water-soaked, crater-like depressions.

Bacterial blight can cause significant premature defoliation and in the worst cases significant boll rot. Where damage is limited to premature defoliation, yields may be reduced by 10 percent or so; when boll rot occurs, losses may exceed 20 percent.

Why now?

Why has bacterial blight suddenly become so important in some fields over the past couple of years? It is a question posed again and again. I have been asked if the disease is coming in on seed. Are some varieties more susceptible? Is the increase due to a change in weather patterns/climate?

We do not know all of the factors that have led to current disease outbreaks. While bacterial blight can be spread through seed, that does not mean it has happened here. Clearly, some varieties are more susceptible than others, but this doesn’t explain where the disease came from initially.

In a paper recently presented at the American Peanut Research and Education Society in Clearwater Beach, Fla., Mace Bauer with the University of Florida Columbia County Extension Service noted:

“Our study compared rain events during the periods of 1955-1984 and 1985-2014. From 1985-2015, we found a statistically significant increase in events where rainfall exceeded 6 inches and statistically fewer ‘good’ events (less than 6 inches). The monitoring network included 259 long-term weather stations in the Southeast. A large portion of the increase in excessive rain events was identified in the tri-state region of Alabama, Georgia and north Florida.”

While unlikely that this trend is responsible for outbreaks of bacterial blight in 2015 and 2016, it does suggest that weather is becoming more favorable with time.

Beyond seed, varieties and violent weather, there may be another answer to “Why now?” The bacterium Xanthomonas citri pv malvacearum (XCM) causes bacterial blight; however there are multiple races of this pathogen, some of which are more problematic than others. Race 18 is quite virulent and the dominant race in cotton in the USA, but there has been much effort to breed resistant varieties. Researchers are now asking if a new race of XCM, one that is able to overcome resistance that has protected our cotton until now, may be emerging.

Control of bacterial blight

For growers with bacterial blight in their fields, the obvious questions are “What can we do about it and how bad will it get?” Unfortunately, there is little that can be done. Use of fungicides and other chemical application will not affect the spread of this disease. Efforts to reduce leaf-wetness periods by irrigating at night may have some small benefit; dry weather may also slow the spread of the disease.

Managing the crop to minimize excessive growth may also help to reduce conditions favorable for disease development and spread. The potential for spread once the disease is established is affected by the susceptibility of the variety and by the weather experienced for the rest of the season.

The most important management decision is not for this season but for next season. Selecting a more-resistant variety and managing crop debris are your best bets for 2017. In the words of Drs. Jason Woodward and Terry Wheeler from Texas A&M University, “If you have bacterial blight in your cotton now, don’t ignore it when planning for next season. Learn from your observations and get to know the varieties you can better plant in 2017.”

You May Also Like