October 5, 2015

China is the world’s largest textile mill user of cotton. China has also historically been the world’s largest cotton producer, although India is projected to surpass China for the 2015 cotton crop year. Nevertheless, what happens in China is very important to the global situation and price level for cotton. It is impossible to talk about cotton without including China in the discussion.

The US textile mill industry peaked in 1997 at usage of 11.33 million cotton bales, and exports that year where 7.5 million bales. The US mill industry began to downsize and shift overseas. By 2002, total off-take was just the opposite—mill use was 7.3 million bales and exports were 11.9 million. Today, US mill use is less than 4 million bales and exports will range mostly from 11 to 13 million bales. With about three-fourths of US demand (offtake) headed to overseas mills, what happens in China and the rest of the world is much more important than 15-20 years ago.

China’s carry-in and build up

Evidence suggests that China likes to have relatively large stocks. Historically, carry-in stocks (ending stocks from the previous crop year) average about 55 percent of mill use. We can only speculate as to the reasons but among them might be:

As a buffer or safety net for its large mill industry.

To attempt to exercise some control over prices.

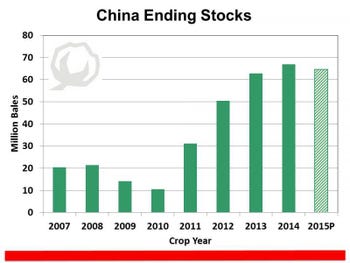

At the end of the 2010 crop year, however, China had only 10.6 million bales to carry forward to the 2011 crop year—the lowest level since 1994 and only 28 percent of 2011 mill use.

Beginning in the 2011 crop year, China began to increase cotton imports. Conventional wisdom is that China ramped up imports in an effort to rebuild stocks. I don’t doubt that but often have wondered if the sheer magnitude of increase was intentional. I have a hard time believing it was.

Beginning in the 2011 crop year, China began to increase cotton imports. Conventional wisdom is that China ramped up imports in an effort to rebuild stocks. I don’t doubt that but often have wondered if the sheer magnitude of increase was intentional. I have a hard time believing it was.

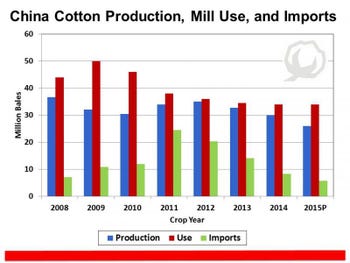

During the 2011 crop year, China imported over 24 million bales of cotton, followed the next year with another 20+ million, and then another 14 million bales in the 2013 crop year. This compares to typical imports of mostly less than 10 to 12 million bales annually. In 2009, China experienced near-record mill—rebounding from a large decline in 2008. This was followed in 2010 by another good year in mill use. In two crop years, 2009 and 2010, mill use exceeded production by a total of 33½ million bales. This resulted in the decline in stocks.

The problem for us and for them

China’s mill use continued to decline further after 2010, however. This downtrend was not likely expected by China. Cotton usage declined 26 percent from 2010 to 2014. This decline in use, coupled with a closing of the gap between China’s production and use and continued imports during this time, lead to the massive buildup in stocks by end of the 2013 and 2014 crop years.

But this doesn’t address the underlying cause—what happened to demand? If weakening demand is partially to blame, why the decline in use? Why would China continue to import when signs suggested it should be doing otherwise?

I am not privileged with first-hand knowledge on the how and why of happenings in China. Among other things, falling use (demand) could have been due to loss of share to synthetic fibers. It could also be due to shifts within the global textile mill business—Vietnam, for example, has become a very significant importer of cotton and its mill industry (now over 4 million bales per year) is expanding at a time when China has been contracting. The increase in imports even with demand declining and stocks rising could also have been due to cotton imports being cheaper than the price/cost of using stocks. It could also be due to fiber quality—mills preferring the quality of US and other imported cotton rather than China’s own stocks.

Mills reject it

The quality of China’s stocks has always been in question. On at least two occasions, government reserves have been offered for sale to Chinese mills and the results have been weak. For either price or quality reasons or both, mills seemingly do not desire the cotton. Some of the Chinese stocks could be at least 2-3 years old. It has been assumed or mentioned by some that better quality cotton imports could be “blended” with these stocks to produce a desirable yarn and product. I am told that Color grade is a problem with the stocks and could further deteriorate over time. I have doubts as to whether or not blending is a possible solution and way to use and reduce stocks.

China’s cotton situation is problematic for us and for them. China wants to reduce its huge stockpile. China wants to reduce imports and said they will import only the very minimum but this remains to be seen. China does not want to reduce price on their stocks and is hoping that prices go back up so stocks can be competitive—but, quality is a problem. If and when stocks do enter the supply pipeline, that may depress prices—something China does not want to do.

The China situation is a real supply/demand contradiction that may take at least another two to three years to begin to work itself out. This doesn’t necessarily mean low prices for US growers. Because of quality concerns and the contradiction in China’s cotton policies, prices may still be “overruled” by global demand, acreage and production in the US and other countries, and the need for quality cotton.

(Don Shurley is Professor Emeritus of Cotton Economics with Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Georgia.)

You May Also Like