How well did pollination work in your cornfields this year? Now is the time to evaluate pollination success.

Pollination got off to an early start in many parts of the Corn Belt. Dry weather interfered and caused a few scattered embryos to go unfertilized or led to tip abortion in some cases. High numbers of Japanese beetles clipped silks in some fields, disrupting pollination.

Overall, though, Dave Nanda believes pollination was successful this year. Nanda, a former corn breeder and now a crop consultant based in Indianapolis, visited a cornfield as pollination was beginning earlier this season to explain how pollination works when things go right.

Inspecting the field as pollination began, Nanda pulled an ear and peeled off husks to illustrate how pollination starts.

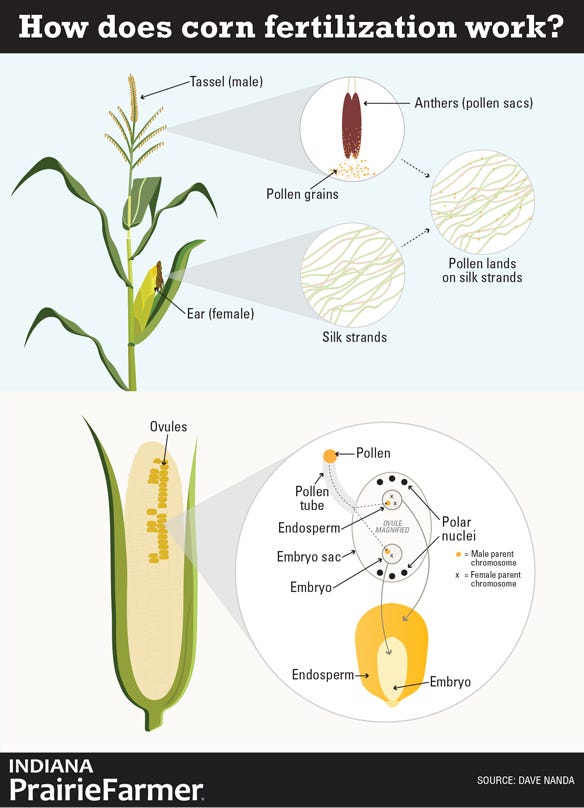

“Pollen grains can land anywhere along a silk,” Nanda said. “Hairs on the silk help catch pollen grains. Once a pollen grain attaches to a silk, it forms a microscopic tube which grows down the silk toward the cob.

“The male portion of pollen reaches the cob and finds an ovule. That’s when fertilization occurs. Each silk is attached to one ovule. If the ovule is successfully fertilized, a single kernel forms.”

What happens next is called double fertilization, Nanda explained. The nuclei split into two halves. Two nuclei from the ovule are fertilized. One fertilized portion forms the embryo, which becomes the “baby” plant. The other fertilized portion forms the endosperm, which becomes the starch portion of the kernel that provides food for the embryo once it germinates.

The process is slightly more complicated than it sounds, and unique to all flowering plants in the Angiosperm family, Nanda added. “When the endosperm forms, it actually gets two sets of chromosomes from the female and one set from the pollen grain of the male. The endosperm has three sets of chromosomes while the embryo, which is the baby plant, has only two sets — one from each parent.

“This difference is worth noting,” Nanda said, “because it explains why some believe the female parent line has more influence than the male. The added influence would show up in traits like grain quality or size and depth of kernels, since the endosperm contains twice as much genetic material from the female as the male parent line.”

The female parent can also have extra impact on seedling vigor, Nanda said. That’s because the endosperm is important in getting the seedling off to a quick start.

Pollination occurs successfully if enough moisture is available and temperatures are reasonable, Nanda said. Pollen shed from tassels typically occurs during the morning hours. Pollination is usually finished by around noon.

Pollination should occur normally unless temperatures rise above 95 degrees F for extended periods, Nanda added. It’s possible to become hot enough to burn pollen grains, but it’s rare, he said.

Possible problems

One problem that can arise is if tassels emerge and shed pollen before silks emerge and are ready to receive it. That doesn’t appear to be an issue in most areas this year, Nanda said. It typically only occurs when dry weather results in moisture stress that delays silk emergence.

Planting two hybrids in the same field that differ by even a couple of days in pollen shed helps reduce the odds that there won’t be any pollen available when silks emerge, Nanda said.

This year there were reports that silks in some fields emerged about the same time as tassels and grew very long before pollination occurred. This may have affected pollination of butt kernels in some fields but isn’t expected to be a large issue.

Once pollination is over, if you peel back husks and shake the ear, fertilized silks will fall away, Nanda said. At that point, any silks still attached indicate where fertilization didn’t occur.

Also check ear tips when assessing pollination success, Nanda said. Those ovules are fertilized last. If stress occurs, they are the first aborted so the plant can produce as many viable kernels as possible.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like