Paul Good and Dale Weaver installed their first center pivot 2007 and say yields have improved considerably on their Noxubee County, Miss., farms. They now have five sprinkler systems, two that are almost half a mile long, the rest shorter. "Each of the systems can be monitored and controlled from my smart phone with FieldNet software," Dale says. "At any time, I can see what each system is doing, what the water pressure is, how much water is being applied, etc. I can change the rate or make other adjustments remotely."

After years with cotton in the crop mix on their Noxubee County, Miss., farms, Paul Good and son-in-law Dale Weaver dropped cotton in 2007 in favor of corn and soybeans, and since then have been adding center pivot systems and concentrating on practices to maximize yields of those crops.

Decades ago, before the bulk of the state’s production shifted to the Delta, Noxubee County was the No. 1 cotton county in Mississippi, and growers here still have some of the highest yields in the state.

Ag news delivered daily to your inbox: Subscribe to Delta Farm Press Daily.

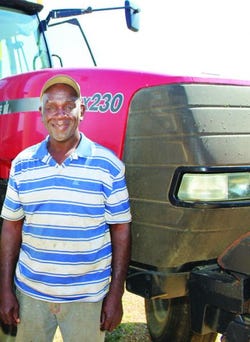

CENTER PIVOT SYSTEMS are an important part of their grains operation, say Dale Weaver, left, and Paul Good. They have five systems, two of which are almost half-a-mile long. All are fed from reservoirs and can be controlled and monitored via smart phone, Weaver says.

“But in recent years, for us, the potential returns have been better with corn and soybeans,” Paul says. “Even after we quit growing cotton, I kept our two pickers — just in case. But we reached a point that we had to make a choice whether to make a big investment to upgrade our cotton equipment, or to commit fully to corn and soybeans. So, we sold the pickers.

“I still think cotton is a wonderful crop,” says Paul, who was honored in 1999 with Cotton Grower magazine’s Grower Achievement Award for excellence in cotton production. “But, it looks like for the foreseeable future, Mississippi is going to be primarily a corn and soybean state, and to produce those crops well, you’ve got to have water.

THEIR SWITCH to all grains necessitated the addition of center pivot systems to help maximize yields, say Paul Good and Dale Weaver. They now have five systems, which are fed from surface ponds, including one of their catfish ponds that was taken out of production to feed a pivot.

“It would be difficult to estimate how many pivots have been installed in this part of the state over the past few years. Most are fed from surface catchment ponds, some from catfish ponds that have been taken out of production. A few producers have drilled wells, but for most part, that’s prohibitively expensive. We’ve taken one of our catfish ponds out of production and are using that water for irrigation. Catfish is only a small part of our operation.

“Our ponds are 4 feet to 6 feet deep and contain about 50 acre feet of water. Our land is terraced, with ditches and grassed waterways, so all the rainfall and all the runoff from our fields are channeled into the irrigation ponds. This also has environmental benefits by preventing nutrient runoff and limiting erosion. The majority of the water we get from rainfall ever leaves our farms.”

They installed their first center pivot 2007 and, Paul says, “Yields have improved considerably on the irrigated land. These black prairie soils hold moisture well, and ours are exceptionally high in organic matter.”

They now have five sprinkler systems, Dale says, two that are almost half a mile long, the rest shorter. “With the Valley and Zimmatic systems, we can water a bit over 800 acres. Each of the systems can be monitored and controlled from my smart phone with FieldNet software. At any time, I can see what each system is doing, what the water pressure is, how much water is being applied, etc. I can change the rate or make other adjustments remotely.

“Before this technology, I’d be out checking on systems at 10 p.m. to 11 p.m., sleeping until daylight, then out checking them again. I can also monitor our catfish ponds on my home computer and can get oxygen level readings by phone.” They shoot for production of 6,000 lbs. to 8,000 lbs. of fish per pond per year.

A substantial yield bump

“We added another new pivot in 2012,” Dale says, “but we had frequent rains after July 4 and never even made one circle with it. Still, I’d rather have had it and not needed it than to have needed it and not had it. Being able to water our crops has made a real difference: We saw a substantial yield bump as we added irrigation.”

FREQUENT RAINS in east Mississippi have been beneficial to soybeans on the Good-Weaver farms.

Corn yields in 2012 were 194 bushels irrigated and 125 bushels dryland; soybean yields were 60.5 bushels irrigated and 57 bushels dryland.

This year, Paul and Dale are farming about 1,475 acres, split about 50/50 between corn and beans. They had 305 acres of winter wheat, averaging about 68 bushels; that land was was double-cropped to beans. They try to rotate their fields between corn and soybeans every year. They rent about 405 acres, the rest is owned.

“In the past, we’ve farmed more — well over 2,000 acres,” Paul says. But because of my age and legacy considerations, I turned the home place over to my son, Philip, and he now farms that. My son, Steve, and his son, Ben, farm here and also in the Delta near Inverness.”

Paul, who will turn 88 later this year, “can get on a tractor or a combine and go all day,” says Dale, who is married to Paul’s daughter, Janice. “He’d rather run a dirt pan than play golf.” The two have farmed together for 30 years, and even before that, Dale worked for Paul in his farming operation.

“I try to keep up all our terraces, waterways, and ditches,” Paul says. “It’s a constant chore, but we want to do all we can to protect our soils, to retain all the water that falls on our land, and to keep runoff to an absolute minimum.”

Technology and advances in equipment have also made a big difference in farming, he says. “Growing up on my father’s farm, we had a 1-row cultivator and a team of horses. We had a Model 37 John Deere tractor for heavy work. Things have changed a lot since those days.

“This year we moved to variable rate planting, which we feel will allow us to better manage plant populations — and we hope, further increase yields. With yield mapping from the combine, we think we’ll better be able to see our strong and weak areas, and that we can improve those weak spots.

“As long as 10 or 15 years ago, we worked with USDA on testing of precision farming systems. We learned a lot from that, using yield monitors on our combines and doing yield mapping. And we still work with them. We’ve also had numerous test plots over the years with Mississippi State University and seed/chemical companies.”

They recently traded up to a John Deere RTK system, which they will use for the first time this year,” Dale says.” We’ll move it between our two big tractors and the combines, and we’ll probably add another unit later after we get some experience with this one. We think the year-after-year repeatability it offers, combined with yield mapping, will be an asset. It also has auto-steer, which we’re looking forward to using this fall.

THIS MACDON FlexDraper head for their John Deere combines is “one of the best equipment investments we’ve ever made,” says Paul Good, left, with son-in-law Dale Weaver. “Grain flows through it like water, and grain loss has been greatly reduced. It paid for itself in two years.”

“We also have a new variable rate CaseIH planter, and we’ll be able to use our yield mapping data with that for even greater planting accuracy.”

They have purchased a MacDon FD70 FlexDraper head for their 9670 and 9660 John Deere combines. “It is one of the best equipment investments we’ve ever made,” Paul says. “It is so much more efficient than what we had previously — grain flows through it like water, and grain loss has been greatly reduced. It paid for itself in two years.”

“We have more combine capacity than we probably should have,” Paul says. “But a few years ago, we lost one to fire at harvest time and it put us in a bind. Now, we the added combine capacity provides insurance against that, and it could be used by one of my sons if they should need it on their farms.”

Their tractors are John Deere 8330, Case IH MX230, and a Case Magnum 290, which they bought just recently.

Variety trials are helpful

Corn varieties this year include Dekalb 6469, 6208, 6757; Pioneer 33N55 and 33N58; Croplan 6640; and Terral 28HR20. Soybeans are Asgrow 4632, Pioneer 95Y80, Delta Grow 4765; and Progeny 4510, 5610, and 5711 — “The latter has been a very good bean for our black prairie soils,” Dale says. “We look at MSU and company variety trials data for two or three years, and factor in what has worked well for us in previous years, and we can pretty well determine what will work for us.”

Their wheat varieties this past season were Pioneer 26R87 and 26R15, USG 3201, and Magnolia. ”We watch wheat disease ratings closely, and they are a factor in the varieties we choose,” Paul says. “We usually plant several varieties in order to spread risk and harvest period.”

DALE WEAVER, from left, his wife, Janice, Paul Good and his wife, Joyce. Paul, who turns 88 this year, says he has no interest in retirement.

Dale notes that Paul is a voracious reader — “He’ll spend hours poring over data from variety trials. He reads every farm publication from cover to cover, and he picks up a lot of insight into production and marketing.”

They’ve been fortunate, Paul says, “to have Mississippi State University just up the road, and the Brooksville Experiment Station adjoins one of our farms, so it’s easy to go there and see their variety trials and determine what might work well on our farms. All their specialists and Area Extension Agent Dennis Reginelli have been so helpful to us. Charlie Stokes, who worked on our farm during his college days at MSU, is now an area Extension agent just up the road at Aberdeen.

“The university and the Extension Service have reached out to farmers over the years, and we’ve been blessed to have access to all their information, research, and guidance. That’s particularly the case in marketing, which is such a big part of our operation. Their marketing schools have been very helpful, particularly in the use of Board of Trade futures and options, and we’ve benefited from their many seminars and short courses.

“We forward contract about two-thirds of our expected production, and we use options as part of our hedging strategy. We’re now in the most uncertain markets I’ve seen in my lifetime, and it’s helpful to be able to use these tools.”

They have on-farm storage capacity of 73,000 bushels, Dale says, with heaters on most of the bins and stirators. “Whatever we haven’t forward contracted, we hold until January or February, when the basis is better. All our corn goes to poultry operations. We market our corn through Hansen-Mueller, Alabama Farmers Coop, and Peco Farms, and all our beans go to Cargill.”

For the past five years, their fertility program has been almost entirely poultry litter.

“We soil test half of our land each year with Brookside Labs and follow their recommendations,” Dale says. “Our fields tend to be wet in the spring and we usually aren’t able to apply litter then, so we make our applications in the fall. We lose some of the nitrogen overwinter, but even so we’ve seen yield increases over commercial fertilizer.

“Since we started using the poultry litter, soil tests have shown improvements in fertility, particularly phosphate levels were way down. But with 2 tons per year, levels are now where they should be, and micronutrient levels have been improved. If tests show we need potash, we’ll use commercial sources.

Poultry litter a better value

DAVE SKINNER has been a valued employee for 40 years, says Paul Good.

“The litter has worked well on our wheat, too. Initially, we were afraid it might cause too much growth with fall application, but we haven’t seen that. We feel the litter has been a real asset to our operation, that we get more for our money than with commercial fertilizer, along with a boost in organic matter. Freight’s a big expense with poultry litter; we get most of ours from the Philadelphia/Carthage areas, less than 100 miles away.”

This season, through mid-July, they’d had no significant insect problems, Paul says.

“Stink bugs are always around, but we can manage them OK. Because we have problems with sugarcane beetles, which are in the soil and damage plant roots, we treat our corn seed with Capture, and we’ve seen very few damaged plants.”

Dale says all their corn and soybean seed is treated. “We use Poncho on corn and we treat all our wheat and soybean seed with fungicide and insecticide.. We think this is insurance that gets plants off to a better start, and we generally have very little replanting.”

“We bed everything in the fall, if we can. All our crops are on 30-inch rows, and we’ve found yields are better than on wider rows.

So far, Dale says, they’ve had no problems with weed resistance. “There have been a few instances when weed kill wasn’t what we thought it should’ve been, but rotating crops and chemistries has helped to keep things under control. And I do a lot of hand-pulling of weeds.”

HIS 1947 STINSON aircraft is useful for spotting any potential crop problems, says Dale Weaver, who also uses it to pick up parts from distant places.

Paul and Dale do most of the work on the farm themselves, but value the assistance of their employee, Dave Skinner, who has worked on the farm for 40 years. They will use some part-time labor at harvest and other busy periods. Paul’s wife, Joyce, and Dale’s wife, Janice, handle the books and records and keep all the farm paperwork in order.

Getting qualified labor is increasingly a problem for farmers, Paul says. “Trying to find someone to competently operate a $300,000 piece of machinery, with sophisticated electronics, is a real challenge. And it’s one that’s somewhat worrisome for me, at my age, with Dale and me doing almost everything ourselves. One thing I think the university ag schools could do is to incorporate programs that let their students get out-of-classroom training through actual work on farms.”

A growing problem for all of Mississippi agriculture, Paul says, is the deteriorating state of roads and bridges. “A lot of our secondary roads are no better than they were 40 years ago. I feel this is hindering Mississippi development, and in many areas is certainly a detriment to agriculture, for which a good transportation infrastructure is vital.”

(For more about the Good/Weaver operation, see Move from Indiana led Paul Good to 40 years of Mississippi farming)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like