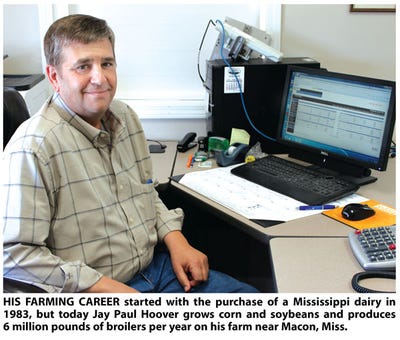

Although he sold his dairy in Noxubee County, Miss., in 2000, Jay Paul Hoover is grateful for the experience he gained from that operation. Today, he farms 1,150 acres of corn and soybeans and has six poultry houses, producing 6 million pounds of broilers per year. “I normally plan for a 50/50 corn/soybean rotation,” he says, “but this year I went a bit heavier on corn. With September corn trading near $7, it was basically a price decision."

In the wide world of farming, there aren’t many who envy the dairyman — too confining, they say, too demanding; all those cows that have to be milked and looked after every day of the year … day after day after day.

An old dairyman once summed it thusly: “You’ve either got to be a masochist or you’ve got to be the rare exception who really loves it.”

Jay Paul Hoover is one of those rare exceptions.

And though he sold his dairy here in Noxubee County, Miss., in 2000 when his father back in Pennsylvania was facing health issues and he thought he would need to return north to take over the family business, he looks back on his 17 years as a dairyman with much fondness.

And though he sold his dairy here in Noxubee County, Miss., in 2000 when his father back in Pennsylvania was facing health issues and he thought he would need to return north to take over the family business, he looks back on his 17 years as a dairyman with much fondness.

“There are a lot of negative impressions of dairying,” he says, “but I enjoyed it immensely. I liked working with the cows and delivering a quality product. It was hard work, and we went through some challenging times in the early years.

“My wife and I would sit down every two weeks and figure to the penny how we would allocate the next milk check — how much for food, how much for expenses, how much toward debt. We did without things, we often just barely scraped by. It was tough, particularly with young children. It’s the kind of situation that can break some families apart, but it brought us closer together, made us stronger.”

Jay, who grew up in Pennsylvania, from time to time would visit relatives in the South. On one of those visits, he met Shirlene, who is from Macon, Miss., a region of highly productive farmland in the prairie region of the state (in the late 1800s, Noxubee County was the largest cotton producing county in Mississippi), and in 1980 they were married.

“I had grown up in farming,” he says. “My father had a row crop and vegetable operation; in addition to all his other crops, at one time he grew 400 acres of snap beans — that’s a lot of beans. He later bought a dairy operation with the idea of converting that land to crops, but ended up continuing the dairy.

“Dairying wasn’t Dad’s first love; I, on the other hand, really enjoyed it, and after Shirlene and I married, a small, dairy operation near Macon came up for sale in 1983. I could assume the owner’s 5 percent loan and the FHA would finance the rest.

“I was young, but I knew dairying inside and out, and I had the confidence to take on the debt. Dad co-signed a note for money to buy cows and equipment, and I was officially a dairyman.

“There were some lean, tough years early on, but five years later we had made every payment on time and I was able to take Dad off my note — a happy occasion! To this day, I’m thankful to the FHA for its young farmer program that helped me get started, and to Dad and the bankers who believed in me.”

Investment turned into career

As things turned out, Jay didn’t go back to Pennsylvania after selling his dairy.

“My father-in-law had a heart attack, and Shirlene and I felt we needed to stay here. I worked in town at Southern Feed & Seed for three years and in 2001 this farm came up for sale.

“I wasn’t planning to farm it, had no equipment; I just bought it as an investment. I leased it out for three years, and when the lease expired, my son-in-law, Andrew Shirk, was wanting to farm, so he and I started farming together.

“Later, when poultry started expanding into this area, Andrew and I built six poultry houses each and separated our operations. Andrew also bought my share of the cattle we had when we were farming together. My other son-in-law, Kevin Shirk, who also farms nearby, built eight poultry houses. We all help each other and share equipment.

“Later, when poultry started expanding into this area, Andrew and I built six poultry houses each and separated our operations. Andrew also bought my share of the cattle we had when we were farming together. My other son-in-law, Kevin Shirk, who also farms nearby, built eight poultry houses. We all help each other and share equipment.

“Although I have no sons, I’ve been blessed that two of my daughters married men who wanted to be farmers and that we can all work closely together.”

Today, Jay farms 1,150 acres of corn and soybeans and has six poultry houses, producing 6 million pounds of broilers per year.

“I normally plan for a 50/50 corn/soybean rotation,” he says, “but this year I went a bit heavier on corn, 700 acres. With September corn trading near $7, it was basically a price decision. We have a mixture of soils, mostly heavy clay, and I put the corn on the best land.

“I plant several different varieties in order to spread risk. This year, I have 10 varieties, mostly Pioneer and Dekalb, but also some Terral and Dyna-Gro, all Roundup Ready.

I plant 111- to 119-day corn, which usually will put us harvesting the first week in August.

“I generally follow a minimum-till program. After harvest, I’ll incorporate stalks and row up so I can burn down in the spring and plant early on beds. I’ll sometimes plant beans on bedded ground, but they are mostly planted flat.

“The fall of 2009 was so wet, we cut deep ruts getting beans out, so we had to do conventional tillage on those fields in the spring of 2010. That was an especially wet spring, so we ended up planting a lot of corn flat on our bottom land. It sat in wet, soggy ground and then the weather turned off dry, so it didn’t develop a good root system. It was the kind of year you want to forget.”

Jay soil tests all his land every other year. Thus far, he says, litter from the poultry houses has met all his fertilizer needs except for liquid nitrogen sidedress for corn. “With nitrogen prices as they are, this is a real money saver.” Lime is added as indicated by the soil tests.

“On my better land, I’ve had some really good corn yields,” he says. “Year-in, year-out I’ll average 143 to 145 bushels, and for dryland corn, I’m happy with that.”

90,000 bushels on-farm storage

Most of the corn is sold through brokers, although some is sold locally. He has 90,000 bushels of on-farm storage, which helps to better manage harvest flow and marketing.

“My soybean system is much the same as corn,” Jay says. “I plant several varieties to spread risk — usually 15 percent to 20 percent late Group IV beans and the rest early to mid-Group V so harvest won’t (most times) conflict with cutting corn.

“This year, I’m planting Pioneer 95Y01 and 95Y70, two Terral varieties, two Asgrow, and one Progeny, all Roundup Ready.

“I look at Mississippi State University test results, as well as those from the Brooksville Experiment Station near here and various seed company test plots in the area, and come up with short lists for corn and beans. And there are always a few varieties that I’ve fallen in love with because they’ve performed really well on my farm.”

“I look at Mississippi State University test results, as well as those from the Brooksville Experiment Station near here and various seed company test plots in the area, and come up with short lists for corn and beans. And there are always a few varieties that I’ve fallen in love with because they’ve performed really well on my farm.”

Soybean harvest usually starts around the end of August or early September. His four-year average for soybeans is about 43 to 45 bushels, and he sells through brokers, to Tom Soya, a local elevator on the river, and to Cargill and Baldwin Grain.

“Because all my production is dryland and weather is always a risk, I forward contract only about 60 bushels of corn and 25 bushels of soybeans,” he says. “2006 really hurt the crops, and I didn’t have crop insurance, so I don’t want to over-commit myself.”

Even though irrigation in the prairie region was long considered impractical because well drilling was prohibitively expensive and water flow was generally not sufficient for pivots, Jay says a lot of systems have been installed in recent years, fed from lakes or catchment ponds.

“We now have Valley and Zimmatic dealers here,” he says, “and interest in irrigation is growing. I have a 15-acre lake and probably will add a pivot next year that will give me a three-quarter circle for coverage on 166 acres.”

Unlike many rural areas that don’t have easy access to the Internet, he is fortunate that a microwave transmission tower is located directly across the road from his home and shop, which allows him to get broadband service for his computers.

“Also, 20 of us farmers went in together and leased space on the tower for a RTK repeater antenna, which provides excellent coverage for this area. I don’t have RTK equipment yet, but when I upgrade my tractor, probably next year, I will have access to these signals.”

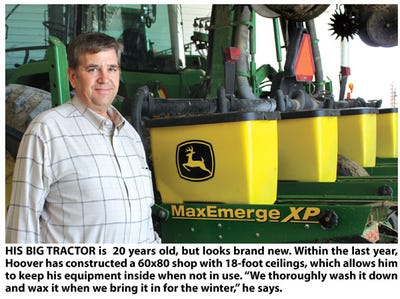

Within the last year, Jay has constructed a 60x80 shop and office building that is heated, has ceiling fans for summertime, and numerous lighting fixtures with long life tubes that brighten the darkest winter day. The shop has an 18-foot ceiling, ample height for his largest equipment and his motor home.

“I like to take care of equipment, so I keep it inside when it’s not in use, and I keep it clean,” he says. His big John Deere Model 8760 tractor is 20 years old and looks brand new. “We thoroughly wash it down and wax it when we bring it in for the winter,” he says.

Expanded into poultry production

In 2006, Peco Farms, the nation’s 11th largest poultry company, headquartered at Tuscaloosa, Ala., began expanding into east Mississippi. The company has a feed mill/hatchery at nearby Gordo, Ala., and processing facilities at Philadelphia, Sebastopol, and Bay Springs, Miss.

“They now have at least 100 houses here and in adjoining Lowndes County,” Jay says.

“Andrew and I each built six 25,000 square foot houses at the end of 2006 and the first flock of broilers went into them in February, 2007. Kevin built six houses about a year later, and then added two more.

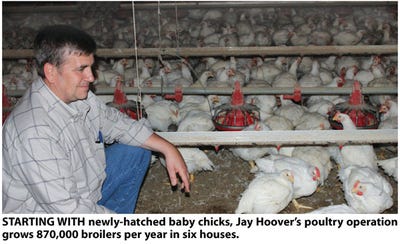

“There are 29,000 birds in each of my houses. We grow them for 51 to 53 days, with the goal of having a 7-pound bird when they’re picked up by Peco. We’ll run 5.5 flocks per year through the houses, for a total of 870,000 birds and 6 million pounds. With a 2-to-1 feed conversion ratio, we’ll go through 12 million pounds of feed each year.

“There are 29,000 birds in each of my houses. We grow them for 51 to 53 days, with the goal of having a 7-pound bird when they’re picked up by Peco. We’ll run 5.5 flocks per year through the houses, for a total of 870,000 birds and 6 million pounds. With a 2-to-1 feed conversion ratio, we’ll go through 12 million pounds of feed each year.

“Under our agreement with Peco, we provide the facilities and the labor and care associated with growing the birds, while they supply baby chicks, feed, and health care. “They’ve got it all down to a science — vaccines are injected into eggs before the chicks ever hatch, and during their cycle here, they are fed four different kinds of rations to promote optimum growth.

“Baby chicks arrive here straight from the hatchery, only a few hours old,” Jay says, “and it’s our job to do the very best we can with them until they leave here a bit over seven weeks later.”

Everything in the houses is automated and computerized — from feeding to watering to heating/cooling, but he says “my manager walks each house four times a day to be sure everything is operating properly, that the birds are getting everything they need, and that they are in top condition. And I check them myself frequently.”

Everything in the houses is automated and computerized — from feeding to watering to heating/cooling, but he says “my manager walks each house four times a day to be sure everything is operating properly, that the birds are getting everything they need, and that they are in top condition. And I check them myself frequently.”

The houses are solid wall and well-insulated, much superior to the old curtain style houses, he says. While winter heating costs are a major expense, he is in a co-op of a hundred or so farmers who pool propane purchases, and “we’re able to get good rates on propane for our heating needs.

“We usually take 10 days or so between flocks to freshen the houses, add new sawdust, and do other maintenance.”

Jay says he is seriously considering adding more houses. “I have my name on Peco’s waiting list for whatever time they expand their operations in this area, with the idea of adding another six houses.

“One of the things I like about poultry is that I can give my employee year-round work, whereas with row crops I’d only need him at certain times of the year.”

And he has compliments for the local ASCS office, which he says “was extremely helpful with all the paperwork needed to get things up and running.”

While Jay’s farming career has taken some unexpected twists and turns since he borrowed money to begin dairying almost 30 years ago, he says, “Farming has been good to me.

“I’ve been blessed to do work I love, to have a wife who has stood by me all these years, three wonderful daughters, sons-in-law who are farmers, and many friends. The Lord has been good to us.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like