Do you do a good job of harvesting and leave little corn behind? And how much left behind is too much?

Pete Illingworth, a farm crew member and combine operator at the Throckmorton-Purdue Ag Center near Romney, Ind., says the first question is easy to answer. You don’t know unless you either stop the combine and take time to look or have a second person checking for you.

“We like to do it when we first start,” he says. “If we see more corn coming out the back or shelling at the head than we like, we start tweaking settings on the machine to get it right.”

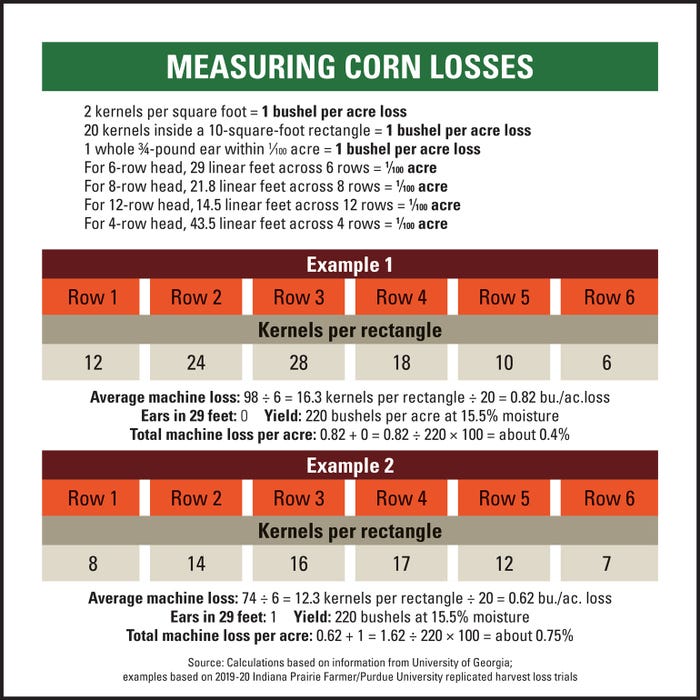

You will get some idea of loss just by moving residue aside and doing a visual inspection. If you want to nail down losses for sure, take time to count kernels. Data from the University of Georgia says in 30-inch rows, 20 kernels found inside a 2.5-by-4-foot rectangle equals 1 bushel of loss per acre. That’s basically two kernels per square foot adding up to 1 bushel of loss.

You also must account for whole ear loss. In 30-inch rows with a six-row head, each three-quarter-pound ear found in a 29-foot rectangular area across the six-row head adds 1 bushel of loss. For an eight-row head, check an area 21.8 feet long by eight rows wide. For a 12-row head, check 14.5 feet across 12 rows.

If you want to pinpoint where losses are occurring, University of Georgia recommends a couple more steps. First, run the combine; then back up and measure loss across each row between standing corn and the machine. Check each row and average the row numbers to get machine loss from the head.

“That’s where we get most of our loss, especially in drier corn,” Illingworth says. Then you need to check with the rectangle behind the combine where it’s dispersing out the back end.

Also look for ears that have dropped on the ground, due to insect damage or lodging, in standing corn. Subtract that number from total loss to get combine loss.

Too much loss?

How much loss is too much is a tougher question to answer. In theory, it’s what the combine leaves once you’ve tweaked it as best you can.

The Georgia study from the mid-2000s, talking about all crops, indicated 2% to 4% loss was acceptable, with 10% not being unusual. Findings from a two-year Indiana Prairie Farmer/Purdue study at Throckmorton indicated it’s possible to achieve much lower losses in corn.

Corn was harvested in replicated plots at three different times both years. Total harvest loss in October, November and December, respectively, in 2019 was about 0.8, 0.5 and 3.5 bushels per acre. The higher December loss was largely due to whole ears lost after a windstorm caused 40% lodging. For September, October and December 2020, the average losses were 0.8, 0.9 and 1.3 bushels per acre, respectively.

Even including the December 2019 loss, that averages to 1.3 bushels per acre, or 0.6%, based on harvesting 220-bushel corn. Without the December 2019 loss, it’s 0.9 bushel per acre, or 0.4% loss, less than one-half percent. Both years, the plots were harvested with a Case IH 2010 model 5088 combine with a six-row corn head.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like