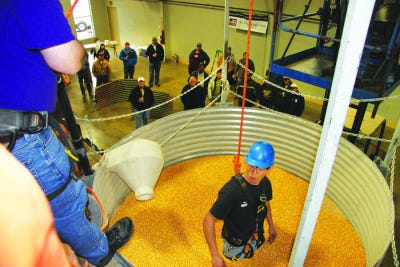

AFTER BEING COVERED waist deep in corn, a lifeline is attached to Tanner Weaver to begin the extraction process.

AFTER BEING COVERED waist deep in corn, a lifeline is attached to Tanner Weaver to begin the extraction process.Twenty seconds — that’s all it takes for a grown man to become engulfed by grain in a storage bin. And even strongest, most physically fit person can’t overcome the weight and force of that grain.

In 2010, according to the Occupational Health and Safety Administration, there were 51 grain bin engulfments in the U.S., resulting in 26 deaths. Additionally, there were hundreds of injuries.

“It was the worst year on record for grain bin engulfments and fatalities,” says Dan Neenan, director the National Education Center for Agricultural Safety at Northeast Iowa Community College.

A RESCUE TUBE is assembled around Weaver.

A RESCUE TUBE is assembled around Weaver.“It’s just part of the unenviable record that agriculture has as as America’s most dangerous occupation,” he said at a Grain Bin Safety Workshop at Sardis, Miss., one of a series sponsored by the Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation. “U.S. agriculture had 551 fatalities in 2011, and averages 70,000 disabling injuries per year.”

Grain bin deaths and injuries are particularly challenging, Neenan says, because it can a long period of time for rescue personnel to reach isolated farm areas, and emergency crews often don’t have the equipment needed and/or are not trained in the specialized techniques needed for rescue from a grain bin.

Rescue can be further complicated, he says, because information is often not readily available about bin layouts, equipment involved, and wiring/shutdown switches.

“The average rescue time for someone in a grain engulfment is 3.5 hours,” Neenan says. “That’s an awfully long time to be trapped in a mountain of grain — particularly if it’s in hot weather and you’re dealing with oxygen deficiency and potentially hazardous gases and dust.”

Suffocation is a leading cause of death in grain storage bins, according to OSHA. Even if a person isn’t trapped in grain, gases from spoiling grain or fumigants and molds can be toxic and can cause permanent central nervous system damage, heart and vascular disease, and even cancer. Carbon monoxide buildups can cause a person to quickly collapse, become unconscious, and die.

Other hazards

WITH THE TUBE in place, grain is sucked out of the tube space with a shop vacuum, creating free space to allow Weaver to be lifted to safety.

WITH THE TUBE in place, grain is sucked out of the tube space with a shop vacuum, creating free space to allow Weaver to be lifted to safety.Other grain bin-related hazards include entanglement in the augur, which can result in amputation or death, unguarded fans, and unexpected loading of a bin.

“An emerging trend is injury or death from grain vacuums,” he says. “We’re seeing three or four deaths a year. In some instances, this occurred when the person doing the vacuuming was talking or texting on a cell phone. Anyone doing this kind of work should give it his full, undivided attention.”

Engulfment in bins most often occurs, Neenan says, when a person attempts to clear grain buildups or clogs inside a bin. Grain can collapse suddenly and in just 20 seconds a person can become completely trapped. “It’s a race you can't win — it can happen so quickly there is no time to react and prevent engulfment.” The situation is even more dire with high moisture grain, which is heavier.

And anyone jumping in to try and assist can also become trapped. “Fifty percent of the fatalities in confined spaces such as grain bins and manure pits are would-be rescuers,” Neenan says. “Last year five members of a family died in a manure pit rescue attempt.”

Grain bins are often located in remote areas, where cell phone signals may be spotty or non-existent, which can make contacting emergency personnel difficult.

Because emergency operations are often centralized, the 911 address for the farm/bins should be prominently posted, he says, and all workers should know it.

In the demonstrations he conducts around the country, he puts volunteers in a scale model bin containing enough corn to cover them waist deep. Neenan and a trained assistant are in the bin to insure that there’s no danger.

Then he demonstrates how a rescue tube can be fitted around the person, and the steps needed to perform the extraction.

Separate sessions are conducted for producers and for firefighters and other emergency personnel.

Unfortunately, the cost of the rescue tube (just under $3,000) means that many emergency crews may not have one available. Often, he says, farmer groups or organizations will pay the cost and arrange for training for emergency personnel. There are also alternative mechanical retrieval devices, and often it is necessary to cut openings in the side of the bin to release grain.

Many states, Neenan notes, require the completion of an entry permit that must be certified by the employer or an employer representative before anyone can enter a bin. But even in states where permits are not required, basic safety steps should be taken prior to entering a bin. These include:

• Locking out and tagging out all means of filling and emptying the bin. This includes mechanical, electric, pneumatic, and hydraulic systems. Lockout kits cost only about $35.

• Have on hand a body harness and lifeline/boatswain’s chair.

• Check bin atmosphere for oxygen content, combustible gases, or toxic agents.

• Adequate lighting.

• Be sure the person entering the bin is trained in safe entry procedures.

• Have a minimum of two standby personnel available to observe and to assist in an emergency.

Putting safety measures in place, having proper equipment on hand, and insuring that all farm personnel are trained in what to do in case of a grain bin accident can “pay a huge return on the investment of money and time,” Neenan says.

The Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation will disseminate information on grain bin safety.

You might also like:

Farmers on edge of fields as spring nears

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like