Think differentSteve Ford says he owes it to himself to take a closer look at high-population narrow-row corn based on limited experience with the practice his farm in 2013.“I am not a big risk-taker, but if you could return an extra $150 to $200/acre, you have to look at it,” he says. “At $4 corn, if it is worth 50 bushels/acre, it would be about a five-year payback on specialized equipment.”He plans to keep the cost of continuing to test high-population narrow-row corn to a minimum. He will double plant with his 30-inch planter and harvest with a soybean platform in 2014.“I am not convinced this is the future at this point,” he says. “I have to test it on my farm, in my conditions, and my methods.”

January 31, 2014

What could be the future of high-yield corn production got a test run on a tiny plot on one of Steve Ford’s best fields in 2013.

Ford, one of about two dozen Corn Belt farmers with similar Stine-sponsored test plots, was more than a little curious about how high-population corn planted in 12-inch rows would stand up – and how it would yield.

“It made 283 bushels per acre,” says Ford, who farms near Redkey, Ind., in northeastern Indiana, close to the Ohio state line. “My combine doesn’t get to see yields like that. There was almost none of it down. That is something you worry about at high populations. The strength of the stalks, surprised me.”

Ford says similar ground planted at 34,000 seeds per acre in 30-inch rows yielded about 220 bushels per acre in 2013, a year that produced his best-ever corn crop. That corn, planted May 15, had a head start on the 12-inch corn, which was planted June 8 or 9 at a 54,000 population.

“In my mind, I do not know how much difference the excellent growing conditions made for the 12-inch corn,” he says. “I am not going to go out and buy a new planter for this. But I am going to play around with it in 15-inch rows on a high-clay nob across from my house in 2014. It intrigues me enough to continue working with it.”

The high-population premise

Corn plant populations – and yields – have been edging upwards in roughly lock step over past 80 years. It’s that correlation that convinced Stine Seed to begin pushing the concept in its breeding program in recent years by selecting for corn specifically suited for populations well above today’s standards.

In 2012, it made a splash when it showcased special-bred high-population hybrids planted in 12-inch rows on its Adel, Iowa seed farm. In 2013, it upped the ante by planting 15,000 acres in 12-inch rows, and rolled out an on-farm trial program with test plots at 26 locations across the Corn Belt.

“We have increased yields by a factor of almost five over the past 80 years, and plant populations are up by the same factor of four or five,” explains David Thompson, Stine national sales and marketing director..

“What that means is that we harvested the same amount of grain per plant in 2012 as we did in 1930,” he adds. Once you understand that, the path to 300 or 350 or 400 bushels/acre is pretty clear. By our math, to harvest 350 bushels/acre, you need something in the neighborhood of 60,000 plants per acre. The question is, how are we going to get that many plants on that acre?”

Stine’s answer? Plant in significantly narrower rows. For example, in 12-inch rows, at 60,000 seeds per acre, plants would be spaced every 8.7 inches. In 30-inch rows, spacing would be about every 3.5 inches at the same population – too close to avoid competition from crowding, says Thompson.

Paradigm shift?

It remains to be seen whether high plant populations and narrow rows are the wave of the future. But many seed companies are testing the concept, although not as publically as Stine Seed, says Mark Licht, Iowa State University field agronomist.

“I would say that most seed companies are looking at pushing their hybrids to see whether they can get better performance at higher seeding rates,” he says.

“Ultimately, this could be a paradigm shift,” he says. “This is going to get us thinking about our corn systems in a new way. All of a sudden, its not just how did this hybrid perform at narrower row spacing. It’s how is it going to perform at ultra high populations.”

Discussing the link between plant population and yield is nothing new, but the big jump in plant populations being tried by Stine Seed is, says Licht.

“For years we have said that the way to increase yields is to put more plants out there,” he adds. “Part of the thinking is based on yield physiology. We are breeding for one ear per plant. Yes, we can get a bit more yield by adding a few more kernels per ear. But in order to get significantly more yield, we have to get more plants out there.”

But that theory often hasn’t been borne out in higher yields in field trials of sub-30-inch corn planted with traditional hybrids at plant populations slightly higher than normal, notes Licht.

However, he contends that researchers have fallen prey to planting hybrids selected for 30-inch rows and 35,000 seeding rates. “One of the major flaws of my own work is that when we have changed row spacing, we have done it with a common hybrid,” says Licht. “I have quit doing these trials because of the difficulty of identifying a hybrid that was developed for that scenario. If we really want to look at ultra high populations, we really have to look at hybrids that were selected for that environment.”

2013 results

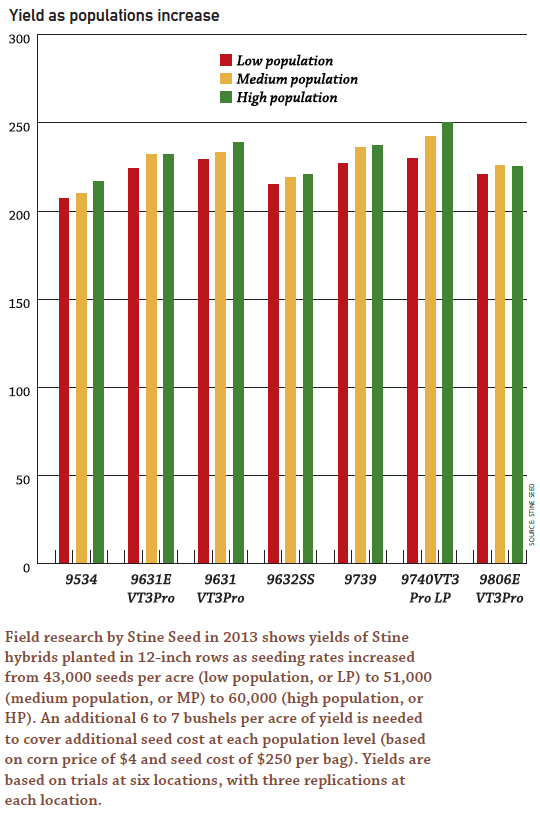

In addition to farmer field trials, Stine Seed conducted trials in 2013 comparing six of its high-population hybrids at four seeding rates (34,000, 43,000, 51,000 and 60,000) and two rows widths (20 and 12 inches) at multiple locations.

In 12-inch rows, the highest populations were the yield winners with four of the six hybrids, The 51,000 seeding rate won or tied with the highest population in the other two face-offs. Winning yields ranged from 225 to 250 bushels/acre.

Thompson acknowledges that adoption of high-population narrow-row corn faces many challenges, including availability of suitable hybrids, planting and harvesting equipment. “Our goal is to demonstrate what is possible,” he says. “We think we are moving this conversation forward.”

In 2014, Stine plans to continue its demonstration program. It also will provide a portion of cooperating farmers’ seed on fields planted to select hybrids at seeding rates above 38,000 and in rows 20 inches wide and narrower.

Logistics

Conditions within a narrow-row field could differ from the 30-inch growing environment enough to require changes, he adds. “How do we sidedress N? How do we spray narrow-row corn? Do we go with a skip row and controlled traffic?” asks Licht. “If we go to narrower rows, we will have to shift our thinking when it comes to general crop management.”

For example, preemergence weed control programs could become more critical because of the challenges of making follow-up applications in the emerged crop. But the crop likely would canopy earlier and effectively control late-emerging weeds earlier than in wider rows.

Differences in in-field airflow based on different spacing and shorter plant stature could affect disease and insect pressure – for better or for worse. “Would we have more diseases in corn, or would they be less problematic?” he asks. “We don’t know.”

Stine Seed says that management practices for ultra-narrow-row corn will have to be refined as more experience is gained. For now, the company recommends that growers testing the concept consider using a fungicide to combat possible heightened disease pressure.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like