The Congressional Budget Office last week provided a grim, if admittedly highly uncertain, forecast of how the COVID-19 pandemic will hurt the U.S. economy. The numbers weren’t pretty: U.S. unemployment, already expected to be the highest since the Great Depression, could remain in double digits in 2021, with GDP plunging 40% in the second quarter of 2020. The downturn could add another $5.8 trillion to the federal government’s budget deficit over the next two years as spending soars and tax revenues stumble.

Typically the currency of a country facing such dire news would plummet. But bad as things are, the U.S. is the safe haven of choice for investors and likely will again lead the world out of this financial debacle. So, for better or worse, the market is betting on the U.S. dollar, sending it to record highs against an index of our 26 largest trading partners.

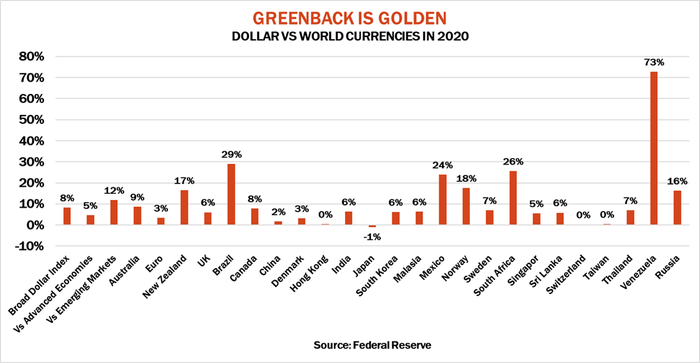

The greenback is up 8% against the currencies of leading trading partners since the first of the year. Emerging markets, including many that compete for exports against U.S. farmers, fared the worst. Their currencies lost an average of 12% against the dollar. The impact of this foreign exchange drama on U.S. agriculture will be a meat grinder of collateral damage from the event no one saw coming.

Currency values don’t affect most export markets directly, at least for crops. Commodities adjust in real-time to changes in exchange rates. Increases in the dollar’s value tend to weaken U.S. crop prices while raising prices farmers elsewhere receive in their local currencies. This arbitrage is yet another factor in play, adding to ongoing trade policy questions and increasing uncertainty about global weather.

Meetings at key central banks this week, including the Federal Reserve, could heighten volatility in currency markets. In normal times, higher interest rates can lure investors to a country’s currency. These times are anything but normal. Official short-term interest rates in the U.S. are close to zero, while some countries are even pursuing negative interest rates.

Central banks like the Federal Reserve set targets for monetary policy, then manipulate money supply operations, rates on funds banks deposit to maintain reserves and other tactics to achieve that goal. In a negative rate environment some central banks charge commercial banks to keep their funds on deposit.

One reason interest rates might move into the red is because a central bank runs out of arrows in its policy quiver. Some believe the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates a couple of years ago so it would be able to cut them if needed – a need that happened sooner than anyone expected.

But with official short-term interest rates at zero and central banks buying longer-term debt to keep financing cheap – so-called quantitative easing – negative rates are a Hail Mary to keep the barbarians from the gate and push money into economies.

Other countries use negative rates to pursue the opposite endgame. The Swiss central bank cut its rate to -.75% to discourage investors from buying its safe haven currency. Leveraged funds have bought the franc recently, even they they’re shorting dollars according to the most recent data from the Commitment of Traders reported by the CFTC.

The strong dollar is also eroding the purchasing power of some of our best customers. The Mexican peso is down 24% against the dollar this year.

The historic wreckage in the crude oil market is one reason for currency problems not only south of the border, but in countries that compete directly with the U.S. for farm exports. The Canadian dollar is down 8% against the dollar this year, while the Russian ruble is off 16% due to the 70% drop in crude oil overseas. In fact, crude accounts for 94% of the 2020 variance in the ruble because Russia depends so heavily on oil revenues.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made existing economic problems in many countries worse as well. So here’s a rundown on the how competition around the world is affected.

Weather complicates wheat outlook

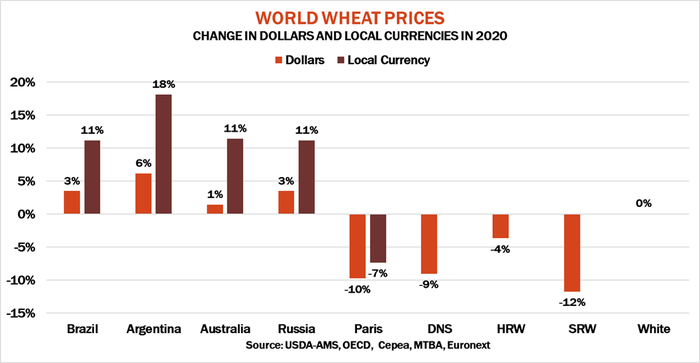

Wheat prices in the U.S. slumped in April despite hopes weather problems in Europe, Australia and the Black Sea region could boost exports for American farmers. Export values for spring wheat are off 9% in 2020 to date. HRW fell 4% while SRW lost 12%.

While drought losses overseas supported wheat prices valued in dollars, the real benefit for growers elsewhere came when those dollars are converted to the local currency. Russian wheat is up 11%, with French wheat in euros gaining 5%. Argentina saw the greatest gains. The peso has been a shambles for years, and lost another 11% in 2020 despite 38% interest rates as the inflation-weary country tries to stave off a ninth default on its debt. Wheat prices in pesos are up 18%, three times the increase in dollars.

Farmers in Australia are preparing to plant another crop following three years of increasing drought misery. Prices on wheat from the eastern part of the continent are up only 1% this year in dollars, but gained 11% in Aussies. The problems down under helped bids for white wheat off the U.S. Pacific Northwest, which are unchanged in 2020 so far.

Bean bull market in China

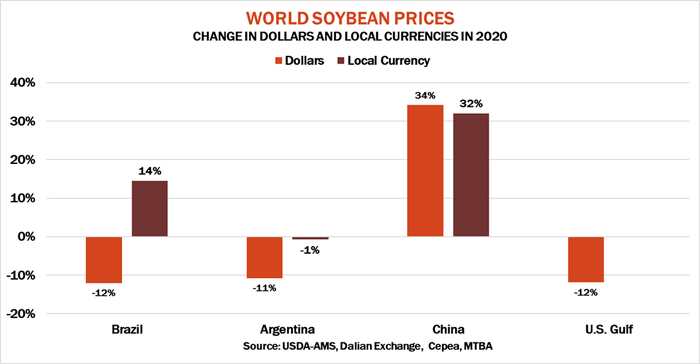

China’s seemingly insatiable appetite for soybeans was hurt by economic troubles and African Swine Fever even before the COVID-19 outbreak started there. But soybean processors are beginning to reopen along with the rest of the country’s economy, helping push soybean futures up 34% this year when valued in yuan. Values in dollars are up nearly as much – 32% -- because the yuan has stayed fairly even with the dollar so far this year. The government still controls the currency but uses other stimulus as it battles an economy growing at the slowest rate in three decades.

The world’s three biggest soy exporters – the U.S., Brazil and Argentina ��– haven’t fared as well, at least in dollars. Prices in Brazil and Argentina are down close to the 12% decline seen in soybean prices at the Gulf this year.

Argentine soybean prices are off just 1% in pesos, but the real winners are in Brazil. In addition to economic troubles and COVID-19, President Jair Bolsonaro faces a political crisis and could become the latest leader there to be impeached. The real is down 29% this year, hitting new all-time lows. So when dollars are exchanged for reais, the value of the soybeans is up 14%.

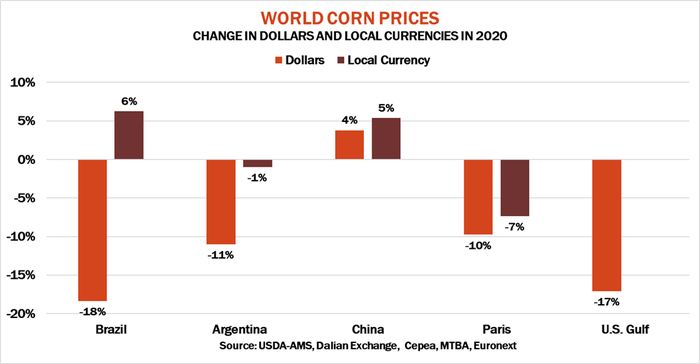

Crude kills corn

With the ethanol industry in tatters due to falling gasoline demand and the bloodbath in crude oil, the price of corn at the Gulf is down 17% already in 2020. French prices are down less but as with soybeans, South American values held up better. Brazilian export prices are down 18% in dollars but gained 6% in reais. The weaker peso also helped prices in Argentine avoid the losses seen in the U.S.

Knorr writes from Chicago, Ill. Email him at [email protected]

The opinions of the author are not necessarily those of Farm Futures or Farm Progress.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like