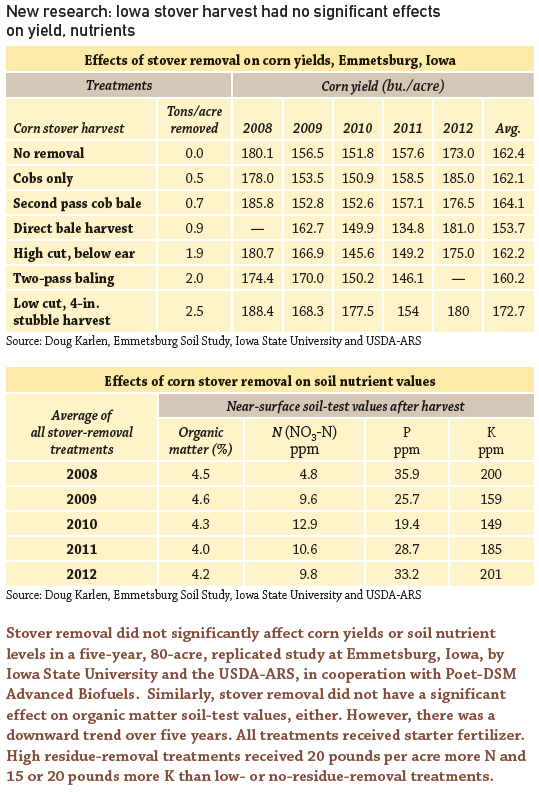

Think DifferentThinking about corn stover harvest?Evaluate each field separately for residue harvest sustainability. Stover removal is not an option on every field, says USDA-ARS Soil Scientist Jane Johnson. “On erodible land, don’t even think about it!”Consult erosion and soil carbon index tools from NRCS before you make a decision. Stover harvest will be most feasible for producers achieving high yields with continuous-corn systems.Maintain a strong fertility testing and nutrient management program.Reduce or eliminate tillage and employ other soil conservation practices.Add a perennial or cover crop to your rotation.Sources: Jane Johnson, USDA-ARS North Central Soil Conservation Lab, Douglas Karlen, USDA-ARS National Laboratory for Agriculture and the Environment

February 16, 2014

Corn stover baling machines rolled across 2,500 acres of harvested cornfields last fall on Mike and Lyle Greenfield’s Jewell, Iowa, farm. The Greenfields’ stover is headed to DuPont’s new 30-million-gallon cellulosic ethanol plant in nearby Nevada, Iowa. The facility is one of two commercial cellulosic ethanol plants scheduled to begin making renewable fuel from corn residue this year. Poet-DSM Advanced Biofuels is building a 25-million-gallon plant in Emmetsburg, Iowa.

In 2013, DuPont and Poet-DSM took in nearly a quarter million tons of cobs, leaves and stalks from about 200,000 acres. The companies are working with several hundred growers in central and northwest Iowa.

These growers are finding that partial stover removal is an effective way to cope with the ever-increasing mounds of residue in high-yielding continuous corn systems, says Dennis Penland, business development manager for DuPont Cellulosic Ethanol. “We’re offering another tool for residue management.”

Want more from CSD? Subscribe to CSD Extra and get the latest news right to your inbox!

The Greenfields have supplied stover to DuPont for three seasons. “Residue management has been a problem for us,” says Mike Greenfield. “With all the stalks in continuous corn, you get a buildup of diseases, it ties up N in the soil,” and impedes soil warm-up and planting. “So getting rid of some stalks is a benefit for us.”

Now, he says, residue harvest “is becoming an integral part of our operation, part of how we manage corn-on-corn.”

Crop residue benefits soil

A 200-bushel per acre corn crop produces about 4.5 tons per acre of dry residue. As farmers know, this residue protects soil from water and wind erosion, supplies nutrients, and builds soil organic matter, which is essential for high productivity.

To maintain soil quality in a continuous corn system under conservation tillage, you need to leave about 2.3 tons per acre of residue on the field, says Douglas Karlen, research leader at the USDA National Laboratory for Agriculture and the Environment (NLAE) in Ames, Iowa. In a corn-soybean rotation, it’s 3.5 tons peracre.

Keep in mind that those are averages, says Jane Johnson, research agronomist at the USDA North Central Soil Conservation Lab in Morris, Minn. Minimum biomass needs vary significantly by soil characteristics and management. “It’s really site dependent.”

The Greenfields, for example, farm “flat and black” ground. About two-thirds of their continuous cornfields receive hog manure, which builds soil carbon. And yields are pretty consistently around 190 bushels per acre. “That’s a big part of why corn stover harvesting works so well for us,” Greenfield says. “Our fertility and soil organic matter are good.”

Biomass removal is not recommended in low-yield environments, or on fields that slope more than 4%, because of erosion risk, says Adam Wirt, Poet-DSM Advanced Biofuels logistics director. “We sit down with growers and look at their fields and maps and offer advice on field selection.” On flat, high-yielding ground in northwest Iowa, he says, “we have ample residue.”

Harvest rates

Poet-DSM collects what it calls a “second-pass cob bale,” which contains about 30% cobs, 45% husks and 20% stalks. “This gives a desirable feedstock, lower in ash, and with more components of the plant from above the ear, where there are fewer nutrients,” Wirt says. Growers are asked to turn off the combine’s chopper-spreader and make a windrow. The baler gathers about 1 dry ton of residue per acre, or roughly 25% of the residue from a 180-bushel corn crop. “Our low take is sustainable, even in a corn-soybean rotation.”

For the past 4 years, grain and cattle producer Rick Elbert, Emmetsburg, has supplied about 600 tons of corn stover to Poet-DSM, some of it collected from fields in a corn-soybean rotation. Elbert farms across an 11-mile radius, which gives him flexibility to choose the flattest and most productive fields each season for stover removal. Since he’s been harvesting residue, he has intensified his nutrient management. “I really watch it carefully.”

DuPont’s target harvest rate is 2 tons per acre on fields with 180-bushel yield, or about 50% of the residue. “We recommend limiting harvest to 3 out of 4 years in continuous corn,” Penland says, “for an average removal rate over 4 years of 1.5 tons per acre — well below the 4-ton limit.” In a corn-soybean rotation, stover collection should be restricted to 2 in 5 years, Penland says, for an average annual removal rate of 0.8 tons per acre over 10 years.

When corn yields drop below 180 bushels per acre, as in 2012, “we reduce harvest rates,” Penland says. Growers report grain yields, and custom harvesters adjust collection, field-by-field. “This is still an art. There’s a lot of judgment involved.”

On Dave and Dan Struthers’ farm near Collins, Iowa, corn stover production in 2012 dropped along with grain yields. Stover removal fell from a goal of 3 square bales per acre to 1.5 – 2 square bales per acre, Dave Struthers says.

The Strutherses, who raise hogs in hoop-style barns, have baled cornstalks for years as bedding. Struthers has observed, “there is quite a difference in biomass among hybrids.” Eventually, he says, “biomass may become a factor in hybrid selection” for growers who want to sell residue.

Tillage reduction opportunity

The Strutherses supplied 600 acres of residue to DuPont in 2013. After the stover was baled, they applied hog manure, followed by one pass with a chisel plow.

Removing some residue from continuous cornfields offers an opportunity to reduce tillage, “the biggest culprit in soil carbon loss,” Penland says. The Strutherses, for example, have switched from a disk ripper to a straight-shank ripper, which “leaves more residue on the surface to protect against erosion,” Dave Struthers says.

“We’re encouraging growers to reduce tillage intensity to save costs and work towards more conservation,” Wirt says, “which will be beneficial to both growers and the land.”

Critics of residue removal — “and there are plenty of them,” says Karlen — complain that “stover harvest increases soil erosion, sediment loss and runoff.” But he’d “trade some residue removal for less tillage. Residue removal is actually preferable to tillage for soil health,” he says. “Tillage destroys soil structure and releases soil carbon.”

What’s it worth?

The Greenfields haven’t changed their tillage practices — they apply liquid manure, followed by chisel plowing — “but we are getting a better seedbed in the spring,” which leads to “more consistent stands,” Mike Greenfield says. “We feel that over the long term, removing some stover may improve continuous corn yields.” Even a 5% yield bump would be significant for growers, he says.

Dupont stover payments cover nutrient replacement costs, primarily for potassium, Greenfield says. The company arranges for harvesting and transporting the bales. Poet DSM pays farmers $20 to $25 per dry ton for custom-baled and transported biomass, or $60 to $75 per dry ton if the grower does the harvesting and hauling. Biomass payments also depend on contract length, delivery timing and other factors.

But selling stover “is not primarily a cash-in-the-pocket deal,” Struthers says. “The real advantage for me is removal of material that harbors disease, and faster warm-up in the spring: it’s the agronomic benefits for continuous corn.”

Growers worry that corn stover harvest could delay fall fieldwork, especially in a wet year. “We may see some growing pains in the supply chain,” as stover collection expands, Greenfield says. “But I’d be willing to put up with some inconvenience for the benefits.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like