Although much of the western Corn Belt has experienced drought over the past couple of years, extreme weather events — including hail and high winds — have contributed greatly to local outbreaks of bacterial diseases in corn.

Adam Haag, Golden Harvest agronomy manager for the West region, is based in Nebraska and knows all about these weather events.

‘The weather extremes over the last couple of years in Kansas and Nebraska, like hailstorms that we’ve experienced, have created disease issues for us from a management perspective,” Haag told viewers at a recent Agronomy in Action webinar series program sponsored by Golden Harvest. “Wind and dust storms last spring created an environment for us with an increased level of disease pressure, so with inoculant in the field, we need to be proactive and be ready to manage those issues that will be out there.”

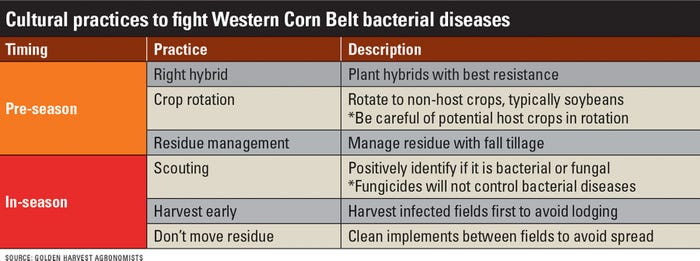

There are general recommendations to avoid infection and the spread of common bacterial diseases. (See table.)

Here are four common bacterial diseases that strike western Corn Belt fields, along with symptoms and potential management strategies from Golden Harvest agronomists:

1. Goss’s wilt. A true Nebraska original, Goss’s wilt was discovered and identified in Dawson County in 1969. “Goss’s can infect corn plants at any growth state, from very early on to late development,” Haag says. “There are two symptoms, including foliar leaf blight and systemic wilt.”

It starts with leaf freckles, and the telltale water-soaked lesions. As it progresses, those lesions kind of ooze out, Haag says. Eventually, it turns to scorching bright orange in color and can be misidentified as heat scorch. “But if you hold the leaf up to light, you can see the shiny surface and water-soaked lesions,” he says.

“Another symptom is the systemic wilt phase,” Haag explains. “If the plants are infected early enough, the disease can go systemic and impact the vascular system of the corn plant, which can end in plant death.” Both symptoms come from the disease entering the plant through some kind of wound.

GOSS’S WILT: Goss’s wilt was first discovered and identified in Dawson County, Neb., in 1969. (Photo by Tamra Jackson-Zeims, Nebraska Extension)

Starting in Nebraska, the disease has increased in distribution to include Kansas, South Dakota, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Iowa, Ohio and Wisconsin over the past couple of years.

“It is moving north and west over the years,” Haag says, “with some years worse than others.” Since a wound is needed to infect, hail and windstorms allow bacterium to enter through these kinds of wounds. Although it is rare, it may actually survive on seeds as well, explaining the distribution into the Eastern states.

To manage Goss’s, producers should look to their seed companies for guidance on hybrids with native genetic tolerance, Haag says. In late season, it is easy to see how hybrids vary. Some hybrids will be completely healthy and others alongside those same plants will show stress, no doubt affecting yields.

“Crop rotation has proven to be one of the best management tools,” Haag says, “but we also need to manage weeds and other plants that could be hosts like shattercane, foxtail and barnyard grass.”

For continuous corn, manage residue. “If you have corn on corn or multiple years of no-till, properly managing residue through fall tillage will slow the spread of Goss’s and give you a better chance to manage it,” Haag adds.

2. Bacterial stalk rot. “We had a small outbreak of bacterial stalk rot in central Nebraska in 2021, within about a 58-mile radius,” says Blake Mumm, Golden Harvest seed agronomist in south-central Nebraska. “You have the bacterium in the soil; it’s everywhere, worldwide.”

There are many different bacteria that cause BSR, but it is most common in hot and humid weather and on irrigated fields using surface water sources such as ponds, lakes, canals and streams. The pathogen has many other host crops such as potatoes, carrots, onions, tomatoes and cabbage, and early on, it looks like Goss’s.

“There is discoloration of the leaf sheath and stalk node,” Mumm says. “You see lesions and some browning on the leaf sheaf. The fields that we watched in 2021, at first, we thought it was Goss’s, but something wasn’t right. The telltale difference between BSR and Goss’s is the foul odor coming from the plant as the tissue decays from stalk rot and becomes dark brown, mushy and slimy. It smells like fermenting corn, but it is foul. Once you smell it, you remember it.”

The other difference, he says, is that not every plant will be infected. There will be hot spots in the field, but it is very random.

“It doesn’t spread from plant to plant unless you have an insect to vector it,” Mumm adds. “It doesn’t impact vascular tissue, and the plants stay green in some areas.” There are corn hybrids that have some resistance to BSR, but it happens so infrequently — maybe every seven or eight years — that it is difficult to get a handle on hybrid tolerance.

“The big thing is fall tillage to incorporate residue,” Mumm says. “This reduces the amount of inoculum. You want to do tillage early in the fall, so there is a lot of time for that residue to break down. Tillage later in the fall or spring won’t give you the benefit.” Rotating to soybeans will also knock down BSR, but it can infect sorghum.

3. Stewart’s wilt. “This is another bacterium we only see once in a while,” Mumm says. “It is vectored by the corn flea beetle in which the bacterium overwinters. Environment can impact survivability of the beetle.” The rule of thumb for beetle survivability is if the average temperatures of December, January and February total 95 if added together for the three months, the chances are high that the beetles will carry over from year to year.

“The two different stages include systemic wilt soon after emergence, due to emerging beetles feeding on emerging young plants, and then leaf blight in the form of pale green to yellow linear lesions after tasseling,” Mumm adds.

Management practices include seed treatments with insecticides that can slow down flea beetle vectoring. Because it is vectored by the beetle that overwinters, culturally, there isn’t much producers can do to slow it down.

4. Bacterial leaf streak. Originating in South Africa on bananas and other crops, BLS strikes field corn, sweet corn, popcorn and seed corn, says Brian Banks, southeast Nebraska field agronomist for Golden Harvest. It was first documented in the U.S. in 2014 and has spread rapidly since, hitting Nebraska and at least nine other states, ranging from Colorado in the west, south to Texas, north to Minnesota and Wisconsin, and as far east as Illinois.

“It continues to spread east and is moving pretty quickly,” Banks says. “It overwinters in crop residue and in the soil surface, and the inoculant base grows well in hot summers and infects faster and easier. The inoculant builds in colder, drier climates, but infects into humid climates. It has progressed into South America already.”

The symptoms of BLS are lesions on the corn leaves that can be brown, tan or yellow, ranging from small flecks to large lesions. “The lesions are different, depending on how long and where the infection has taken place,” Banks explains. “Exudates are jagged or wavy, with a yellow hue. Typically, they move from the bottom to the top of the canopy, and they tend to ooze. The lesions are ‘back-lit’ when held to the light, with a yellow ‘halo’ around the lesion when held up to the sun.”

Banks says that BLS looks similar to gray leaf spot, which is fungal, but with GLS, the lesions are blocky with straight edges.

BLS is spread by wind events blowing soil and crop residue. Early-season rain events and irrigation treatments move the bacteria onto emerging plants. After this primary inoculation, it starts to progress inside the plant and create lesions. In the late season, there is a secondary inoculation.

“Wind events that damage leaf surfaces allow the bacteria to get inside the plant easier,” Banks says. Fungicides don’t work, and bactericides are ineffective to control BLS.

“The big management practice is crop rotation and letting the residue break down over time,” Banks says. “Think about how we are moving implements field to field, and be sure to make sanitation of equipment important, so we don’t move residue from a field where we know we have BLS.”

Tillage will help, along with hybrid selection. “Weed control is important in controlling BLS because there are other host crops and weeds like oats, as well as shattercane and foxtail, for instance,” Banks adds. “In a soybean rotation, keep volunteer corn controlled so you don’t create a bridge where it can spread into the next corn crop.”

Having overall healthy crops, with proper fertility, will also help the plants protect themselves from BLS.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like