December 19, 2019

People across Iowa with interests in conservation and water quality come from all walks of life, education, employment, personal history and areas of interest. With their varied backgrounds, each sees problems and prospective solutions through the lens of their own knowledge, experience and perspective.

This diversity of approach and opinion shouldn’t surprise anyone, but most of us still seem to have difficulty stepping back to see systems that underpin many issues of concern from a broad and unfiltered vantage point.

At a recent workshop held on the campus of Iowa State University, participants including graduate students, state agency professionals, conservationists, educators and farmers spent two days breaking down some conservation issues and approaches to reexamine them using an approach called “systems thinking.”

The workshop was conducted by Benjamin Turner, assistant professor in Agriculture and Natural Resource Management Systems Modeling at Texas A&M University-Kingsville. He introduced the group to the theories and principles that govern the behavior of complex systems, and the methodology and tools developed for problem-solving related to management of natural resources.

The program was sponsored by Iowa Learning Farms, Iowa Nutrient Research Center and ISU Extension. Through large and small group activities, the workshop participants applied a systems thinking angle in examining today’s best practices that address some of Iowa’s environmental issues.

Jacqueline Comito, ILF director, says taking a systems-thinking approach to solving some of the stickiest issues with water quality and natural resource planning makes a lot of sense. “It’s crucial to grasp that we all bring our own biases and vantage points to the table when working together on matters such as nutrient reduction in waterways. Systems thinking is an approach that forces everyone to take a step back and assess a broader systemic view, which can be very eye-opening, even for professionals who’ve been immersed in solving problems for many years.”

Conventional thinking vs. systems thinking

Some of the differences in conventional and systems thinking begin with the definition of a problem. In conventional thought, it’s common to follow a logical and linear step-by-step process addressing problems as they arise. This can lead to many “little fixes” that can often spawn new problems, often undermining the short-term gains that have been achieved. A systems-thinking approach peels back the layers of obvious problems to reveal the underlying systemic contributors and causes that can then be addressed to alleviate the issues for the long term.

Another common desire is to assign blame. Name the bad actors that are causing the problem and expect, or force, them to fix things. This sets up an adversarial construct that seldom yields satisfactory outcomes for any party. Systems thinking encourages the involvement of all parties in contributing to the analysis and the solution. It does take time and effort, but the results over time are almost always more beneficial than traditional approaches.

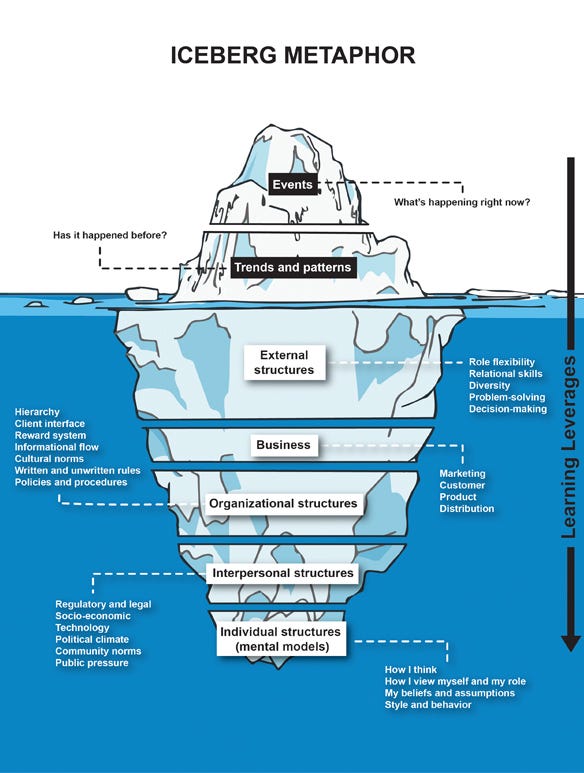

Seeing beneath tip of iceberg

Systems thinking can be explained through the iceberg metaphor. In short, it’s easy to see the 10% of the system that stays above water, obvious and tangible events and trends, but the 90% lurking below the surface must be understood if meaningful actions are to produce long-term benefits.

One farmer attending the program noted, “What struck me the most was the desire many people have to immediately solve a problem. Watching the participants start to slow down and ‘admire the problem’ was very powerful to me. As a farmer who relies heavily on university staff, it was encouraging to see these bright and talented people learn a better way to think about and communicate the very complex issues agriculture faces.”

Don’t just do something; sit there!

Taking immediate and decisive action to “fix” a problem — without fully contemplating and assessing the larger system — typically either delivers no long-term benefit or often makes matters worse in the long run. One outcome of the workshop discussions was the idea that short-term fixes typically treat a symptom that is observed, but don’t address the underlying cause. For example, you may take a pain reliever to reduce a fever (symptom), but it does nothing to address the illness causing the fever.

An ISU Extension faculty member said, “I’m guilty of linear thinking, in that ‘more boots on the ground’ was one of my go-to ultimate answers. After the workshop, I see a need to rethink some issues in terms of events, trends and structure to effectively address them.”

When decisions and actions are predicated on the above-water 10%, often the results are short-term and may ultimately not deliver the desired outcomes. Comito cited one example in financial supports for cover crops. The programs did generate interest and enticed some farmers to adopt the practice. However, the programs set an untenable expectation that adoption is a direct financial transaction rather than a broader business decision based on the intrinsic benefits of erosion prevention, nutrient retention and increased productivity. In her opinion, this is a causal loop that has hindered broader cover crop implementation.

Grasping cause and effect

A key concept of a systems-thinking approach is the understanding of causal loops. An action has an effect that causes a result — sometimes desired and sometimes unintended — which in turn has effects beyond the original intent. This is seldom, if ever, a simple linear process when you look beyond the surface.

These cause-and-effect relationships within a system can produce ripples that extend well beyond the original issue being addressed. Understanding causal interactions and modeling the 90% of the system below water will enable identification of solutions with better long-term potential for positive benefits.

Looking at bigger picture

In general, most people believe they take a big-picture approach to problem-solving; however, we don’t fully understand what may exist beyond our personal sphere of knowledge so we can’t assume our vantage point gives us an accurate big-picture view.

In their post-workshop feedback, one doctoral student noted, “I went into the workshop thinking I’m a ‘systems thinker,’ but the feedback loop exercises made me think that I have been more of a linear thinker. I tend to think about inputs and outputs [or] outcomes, without considering how certain problems may amplify themselves or make solutions more infeasible.”

Systems produce results that they are designed to produce. The best way to influence or redirect system operation is to zoom out to a broad enough view to see the hidden innerworkings that produce the ultimate results. When applied to conservation planning and problem-solving, systems thinking has the potential to help our state overcome many long-standing and difficult environmental challenges.

Pierce is an ISU Extension program specialist with a focus on water quality with Iowa Learning Farms.

You May Also Like