Think DifferentLandowners and public and private conservation organizations are working together to restore oxbows in the North Raccoon and Boone River watersheds in north central Iowa. Their goal is to improve fish and wildlife habitat and clean up nutrients in tile water. Whenever possible, subsurface drainage is routed into the oxbow. Landowners, along with the following participants, have completed more than 60 restorations:U.S. Fish and Wildlife ServiceFishers and Farmers Fish Habitat PartnershipIowa Soybean AssociationSand County FoundationThe Nature ConservancyIowa Department of Natural Resources

July 14, 2015

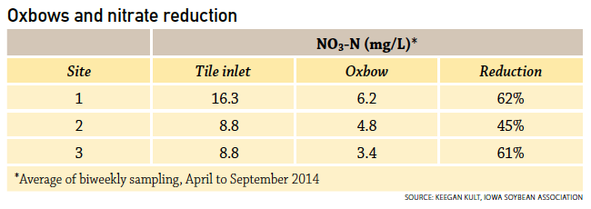

Old stream channels are helping to clean up farm drainage water in north central Iowa. Restored oxbows in the Boone River Watershed reduced nitrate concentrations in tile water by about 50%, according to water monitoring data gathered by the Iowa Soybean Association.

Oxbows are ponds that form when a river’s wide meander is cut off from the main channel. These floodplain formations are very common in the prairie pothole regions of the Farm Belt.

Functioning oxbows provide many conservation benefits, including critical fish and bird habitat and flood control, says Aleshia Kenney, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Moline, Ill. Like wetlands, oxbows also filter nutrients in runoff and tile water from nearby farm fields, improving water quality. But over time, oxbows fill up with floodborne sediment and lose their conservation advantages, she says.

Chris Jones, an environmental scientist at the Iowa Soybean Association (ISA), has a simple method for revitalizing silted-in oxbows: Scoop out the accumulated sediment down to the gravel streambed and re-seed the banks with native grasses. “Whenever possible, field tiles are routed into the oxbow, which can process the nutrients before the water enters the adjacent stream,” he says.

Restoration work

ISA worked with landowner and retired John Deere dealer Gaylord Jones of Woolstock, Iowa, and his grandson, Rory Sterling, to restore a half-acre oxbow on White Fox Creek, a tributary of the Boone River.

Jones, 96, is a devoted conservationist. He has invested in other water quality practices on his land over the years, including tree plantations on erodible ground along Eagle Creek and White Fox Creek and an edge-of-field bioreactor to treat subsurface drainage water.

“We did the oxbow restoration for both wildlife and water quality benefits,” Sterling says. The oxbow harbors hundreds of small fish and is used by shore birds, ducks, frogs and other wildlife, he adds.

The Jones project is one of three White Fox Creek oxbows coupled with drainage outlets. The project began with aerial imagery to identify comma-shaped oxbow depressions. “It’s easy to pick them out on the landscape,” says Keegan Kult, the ISA environmental programs manager who oversaw the restoration.

Because oxbows are in the floodplain, they are usually uncropped, so productive land doesn’t have to be sacrificed – a big selling point for farmers, Kenney says. The Jones’ oxbow is located in a marshy CRP area.

Average nitrate-N concentrations in restored oxbows were significantly lower than in the tile drainage emptying into the oxbow, according to water monitoring data gathered by the Iowa Soybean Association and The Nature Conservancy. Site 1 was sampled 16 times from April to September 2014. The other two sites were sampled 14 times during that period. Researchers don’t yet know how much of the water quality improvement is due to nutrient removal by vegetation and denitrifying microbes in the oxbows and how much is due to dilution with relatively clean groundwater seeping in, says Keegan Kult, Iowa Soybean Association environmental projects manager. Future monitoring will answer those questions.

Dredging, which is regulated by the Army Corps of Engineers, was done in December 2012, at the height of the 2011–12 drought. “We excavated down about four feet, the difference in elevation between the oxbow and the adjacent stream,” Kult says. They hauled the rich, black sediment out of the floodplain and spread it on a nearby field as high-quality topsoil.

Despite the severe drought, groundwater immediately seeped into the excavated oxbow. Groundwater sustains a year-round water supply and prevents the oxbow from freezing solid in the winter, Kult says. In addition, two nearby tile outlets empty into the Jones’ oxbow.

Oxbows also store floodwater. When the river spills its banks, the ponds are inundated, reconnecting the oxbows to the main stream. “That’s how fish populate the oxbow and move back into the main stream,” Kult says.

The cost of an oxbow restoration, which depends on size and the amount of earth moved, is about $4 per cubic yard of dirt, he says. Typical oxbows are one-third to one-half an acre in size, four to five feet deep, and cost around $10,000. After re-seeding, there are no maintenance expenses. Restorations may qualify for cost-share funds from the Natural Resources Conservation Service EQIP program or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program, which has overseen $400,000 in oxbow improvements in north central Iowa.

Routing tile water through oxbows

There have been more than 50 oxbow restorations in the North Raccoon River watershed since 2002 and nearly a dozen in the Boone River Watershed. The first were aimed solely at creating off-channel habitat for the endangered Topeka shiner, says Kenney. Oxbows near tile outlets were ruled out because the effects of farm drainage on this small minnow were unknown.

Subsequent research has found that the fish can tolerate tile effluent. “Now we are looking for sites where we can route tile water in,” Kenney says.

The Sand County Foundation, the Madison, Wisconsin-based conservation group that paid for the Jones restoration, is currently interested in oxbows’ potential to reduce nutrient loads in the Greater Mississippi Basin. “We try to promote new or underused conservation practices and watershed-scale approaches to water quality management,” says Joseph Britt, the foundation’s director of agricultural incentives programs.

About 90% of the heavily tiled Boone River watershed is in corn and soybean production. Field tile drains are a major pathway for both nitrates and dissolved phosphorus, Britt notes. White Fox Creek, which is within the stream network that supplies municipal drinking water for Des Moines, has elevated nitrate-N levels.

The Iowa Soybean Association is working with The Nature Conservancy to monitor the nitrogen and phosphorus content of drainage water emptying into and flowing out of the three White Fox Creek oxbows and tile outlets. Water sampling during the 2014 growing season found that nitrate-N concentrations in the oxbows dropped by about 50%. Effectiveness will vary with rainfall and weather, Jones adds, but the first year of data suggests that oxbow action is similar to bioreactors or controlled drainage.

Vegetation in the oxbows also sequesters dissolved phosphorus, a nutrient linked to algae blooms.

Oxbow incidence

Oxbows are common on prairie streams throughout the Midwest, Kenney says. In the Boone River Watershed, which drains about 900 square miles, researchers have identified up to 100 potential oxbow restoration sites.

“We believe this strategy can be implemented successfully in other farmed landscapes,” Kult says. “The practice offers multiple benefits and could have wide application across the Corn Belt.”

For more information, watch this video from The Nature Conservancy on Boone River oxbow restorations.

Water quality tools that fit

Oxbows don’t exist on all rivers. For example, the Wisconsin River, a tributary of the Mississippi, has no oxbows, says Joseph Britt, director of agricultural incentives programs for the Sand County Foundation, a Madison, Wisconsin-based conservation group.

Still, there are plenty of meandering streams like those in Iowa’s Boone River Watershed. “In the central and southern Corn Belt, oxbow restorations have the potential to be another effective tool in the tool kit to remove nitrates before they flow into rivers,” Britt says.

The Sand County Foundation, which works in five Midwestern states, is also testing other practices that farmers can use to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus runoff, including field-applied gypsum and constructed wetlands.

“We have many tools — and not all can be used everywhere,” Britt says. “It’s not a matter of comparing one technique to another, but rather of finding what works in a particular watershed.”

Fish nurseries

Restored oxbows provide excellent off-channel fish habitat. Fish species found in White Fox Creek restored oxbows during an April, 2014 fish count included the following:

Bigmouth buffalo

Bigmouth shiner

Black bullhead

Bluntnose minnow

Brassy minnow

Common carp

Common shiner

Creek chub

Golden shiner

Green sunfish

Sand shiner

Spotfin shiner

Stoneroller

White sucker

Source: Iowa Soybean Association and Iowa Department of Natural Resources

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like