April 9, 2014

Iowa farmer Tim Smith reduced the nitrates in his tile drain water by 29% compared to the stream levels it drains into.

Already known for being very conservative with his nitrogen rates (0.8 lb./bu. of yield goal) and using BMPs, he was surprised that his 2011 tile nitrate benchmark readings were higher than the stream’s nitrate content. “The first year I enrolled in the Mississippi River Basin Initiative (MRBI) program, my farm’s tile water had higher nitrates than the stream where it drained,” he says.

“My daughter lives near Des Moines and drinks water downstream from my tile lines’ discharge. I was shocked to think that what I thought were sound agronomic practices like ridge-till, N application rates below 150 pounds per acre and MRTN nitrogen calculations were contributing to poor water quality for her and others,” Smith says. MRBI is a USDA-NRCS program in targeted watersheds to reduce agricultural impacts on the Gulf of Mexico dead zone.

Smith jumped into action in 2011, adopted strip-till, flew on cereal-rye cover crops, delayed his fall nitrogen applications to spring and sidedress, installed a bioreactor on some fields, and enrolled in the Mississippi River Basin Initiative (MRBI) offered to Boone River watershed farmers. “Water-nitrate level reductions are possible with proven practices, without reducing yields,” he says.

He also uses a cornstalk nitrate test and V10 leaf tissue test to assess in-plant N levels during and after the growing season. “You need to do these test for 5 years to develop a feel for what you did,” Smith says.

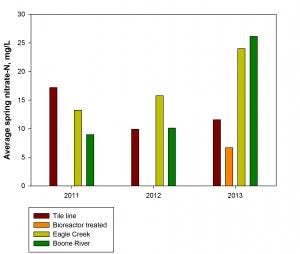

After implementing these practices, peak nitrate levels in Smith’s tile outlets were half those in Eagle Creek, based on 2012 and 2013 tests (see bar chart). The cereal rye is particularly effective in reducing water nitrates because it “nabs them when crops aren’t there to use them,” says Bruce Voigts, MRBI coordinator for the Boone River Watershed that surrounds Smith’s 850 acres.

Click for larger table.

“Cover crops improve soil structure and stabilize yields in challenging weather. And they sequester a lot of nutrients that would otherwise leave the farm,” Smith says. “Cereal rye grows when it’s as cold as 38 degrees, so I see it in March.”

“Later in the year, it releases at least 30 pounds of N per acre later, based on actual dry-matter nitrate measurements that MRBI took from my cover crops. People ask me what it costs to seed a cover crop ($25/acre), and I ask them what it costs them not to plant one, in lost nutrients and eroded soil. A study by Iowa State Economist Mike Duffy figured you lost $10-15 per acre per year in soil loss alone in our county here.” When you add to that losses in land quality, water quality and fertilizer, the state average is $340 per acre, although each situation is different.”

Grow his own seed

Smith is so impressed with cereal rye’s anchoring of soil and nutrients, building soil structure, and extending the microbial growing season that he hopes to add it as a third crop (for seed) in rotation on some of his ground. “I’d like to have the flexibility of having seed on hand to optimize planting for the weather,” Smith says.

“Once farmers see strip-till done well, you can’t turn them away from it. You have to like applying nutrients at planting and having such an ideal spring seedbed. Being able to plant and apply fertilizer in one trip makes sense.

“Even with the wet spring we had in 2013, I wasn’t any later to plant than any conventional farmers nearby.”

Applied science

Two-thirds of Smith’s ground involves comparison strips to test various treatments. For example he tested spring-applied N to sidedress-only, but the wet spring and replanting fouled up his maturity comparisons.

He’s also dabbled with the Field to Mark Fieldprint calculator, which measures inputs (energy, water quality and volume, soil carbon, conservation, land use and greenhouse gas emissions) confidentially. He can benchmark his own progress and compare himself to similar county and national peers. “When I think about farm energy use, I think about fuel and propane, but this calculator takes you back through the value chain, and now I realize how much energy goes into nitrogen fertilizer.”

Avoid regulations

Having seen the results of the MRBI-related program firsthand, Smith reaches out to farmers and the public. “I think that the (Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy) goal of reducing nitrates by 41% in Iowa’s waterways is attainable with widespread farmer participation,” he wrote in a recent opinion piece.

“Once farmers see the dollars associated with erosion and nutrient loss, these soil-health changes won’t be such an uphill climb,” he says.

“Cover crops and reduced tillage are just as big a change today as selling the moldboard plow was for my dad in the 1970s. The people who bought his plow asked how he’d farm without it.”

“If farmers don’t voluntarily reduce nutrient losses, people outside of agriculture will push hard for unproven regulations that affect farming in adverse ways we haven’t yet imagined,” Smith says. “I don’t think farmers understand how concerned the consumer is about where their food comes from and how it’s grown.

“I raise seed for Pioneer soybeans, and they are big on independent ISO certification, to verify how things are done. One farmer here is ISO-9000-certified, and we’re all heading in that direction.”

Last summer Smith hosted a group of food companies with these concerns in mind.

“I know Unilever wants a high percentage of its raw ingredients grown sustainably; will Walmart buy all its products the same way? It has vast resources to devote to this. This trend is going to find farmers getting to know our farms in new ways. My tile nitrate level is just as important as stuff like my soil type and farm legal description.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like