May 18, 2018

----------

Think Different

You may be tempted to just go out and clean an old drainage ditch or add some tile to a wet field you fight to farm each spring. But that could be a risky move, if you receive USDA benefits as most farmers do, and you don’t know the wetland status of the field.

Wetlands were considered wasteland in the early development of the United States, but after more than half the natural wetlands in the U.S. were drained by the 1980’s, growing national concern about that loss and an appreciation for the value of wetlands in the ecological system led to Congressional action for their protection.

If you want to be safe instead of sorry, and don’t want to risk losing benefits from USDA programs including crop insurance and conservation incentives programs, check with NRCS before you drain, clear trees, or otherwise manipulate a wetland so that it can be cropped.

----------

If you’re considering a new drainage system or improving drainage on an existing system, it’s in your best interest to first get a wetlands determination from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) for the wet soils on your farm.

Check First. If you plan to alter a drainage system, whether it’s with a ditch or underground tile, it’s in your best interest to check with NRCS first for a wetland determination. You often can’t tell if an area is a wetland just by looking—it may or may not have hydric soils, or if under normal circumstances would support vegetation normally found in saturated conditions. This site is a wetland—it’s being farmed with no attempts to drain it—but it looks like other areas that are not wetlands. You could lose USDA benefits if you drain or otherwise alter a wetland by increasing the scope of drainage.

A wetland determination is a technical decision made by an NRCS specialist regarding whether or not an area is a wetland. To maintain USDA eligibility, any landowner or producer participating in USDA farm programs must certify in writing, on form AD-1026 at the Farm Service Agency office, that they have not produced crops on land converted from wetlands after December 23, 1985, and did not convert a wetland after November 28, 1990, to make agricultural production possible.

“The decision is a technical one, but the thing for producers to remember is the United States adopted a federal policy of ‘no net loss’ of wetlands about 30 years ago,” says South Dakota NRCS State Conservationist Jeff Zimprich. “Congress included a ‘Swampbuster’ provision in the Food Security Act of 1985 intended to stop the loss of wetlands on agricultural lands; landowners and producers who would further drain wetlands after the provisions went into effect on December 23, 1985, would face potential loss of USDA benefits.”

Wetland is a technical decision

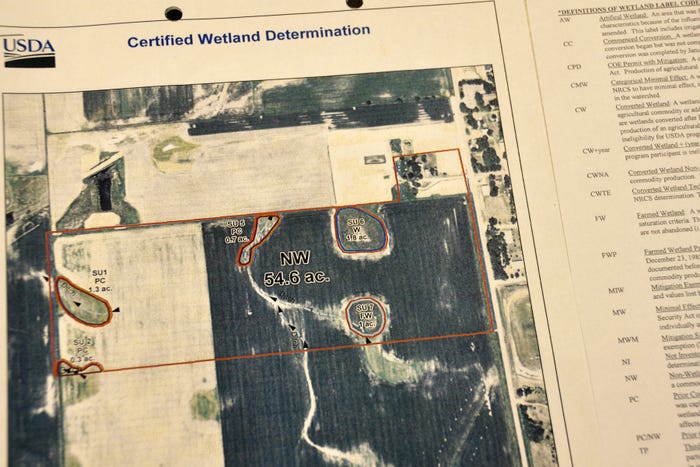

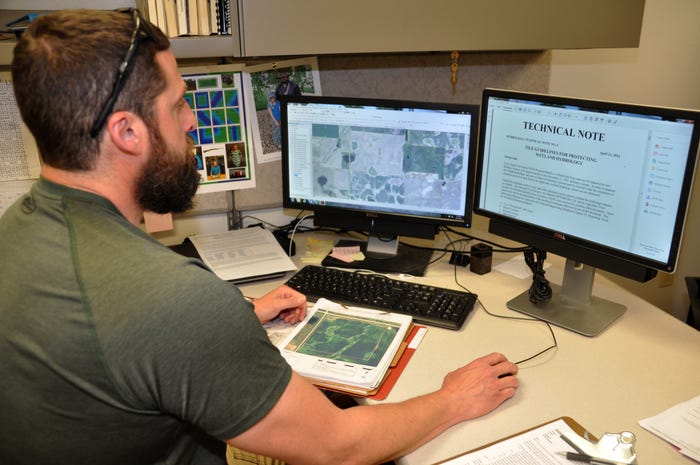

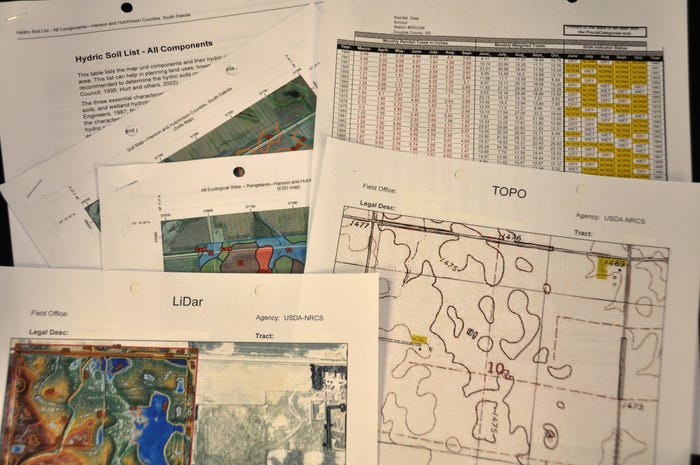

After a producer requests a determination on form AD-1026 at FSA and locates the area on an aerial photo, a specialist at the local Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) uses hydric soils maps, topographic maps, FSA aerial photos, wetlands inventory maps, observations of plants and landscape features, and other science-based tools to make a certified wetland determination. The area may be designated a wetland, farmed wetland, prior converted wetland, farmed wetland pasture, non-wetland or other designation, and will be delineated on an aerial photograph.

Your wetland determination from NRCS will include a map with the wetland determinations symbols and an accompanying listing of definitions.

Don’t expect a determination on the spot. Much work can be completed in the NRCS office, but if a site visit is needed for further investigation, the time required depends on the factor needing further evaluation. A soils evaluation, for instance, requires the soil not be frozen or in standing crop, depending on its location in the field.

Wetland determinations requests are handled in the order in which they are received. “We had a backlog, but we’ve worked to eliminate the really long waits,” Zimprich says. “The current workload in South Dakota allows for a determination to be completed and returned within 6 months, dependent on weather and time of year the request is received—in some cases it’s much quicker than 6 months.”

NRCS Wetland Specialist Deke Hobbick says even though there is enough data to make calls offsite, it’s important that the conservationists involved understand how the wetlands function in the landscape throughout the area they’re working in.

Wetland category definitions

A wetland is an area with a predominance of hydric soils that are inundated or saturated by water. Under normal circumstances a wetland also supports vegetation normally found in saturated conditions. Initially, three categories of wetlands were defined:

Wetlands drained or altered between December 23, 1985 and November 28, 1990 are called converted wetlands (CW), and farming this land or altering it further can result in loss of USDA benefits.

Wetlands that were drained or altered before December 23, 1985, were capable of being cropped, and did not meet farmed wetland hydrology criteria are called prior converted (PC). These lands were grandfathered in and are not subject to the wetland provisions.

Farmed wetlands (FW) and Farmed Wetland Pasture (FWP) are wetlands that were manipulated in some way—usually by installing a tile line or ditch to partially remove water from the area—before December 23, 1985. However, the partial hydrology removal resulted in a site that still functions as a wetland, with surface water or soil saturation that still meets inundation or saturation criteria for a wetland. FW is a site that was manipulated and farmed prior to December 23, 1985 and FWP is a site that was manipulated but never farmed prior to December 23, 1985. These areas can continue to be maintained at the same scope (same dimensions of ditch or tile) and effect (same effect of manipulation on the wetland) as before December 23, 1985, with no loss of USDA benefits, as long as they are not abandoned.

NRCS uses hydric soils maps, topo¬graphic maps, FSA aerial photos, wetlands inventory maps, observations of plants and landscape features, rainfall data, and other science-based tools to make a certified wetland de¬termination. Understanding the landscape is critical to utilizing the offsite tools.

In total, the USDA NRCS uses nearly 20 definitions and labels to describe various wetlands situations. It may not be apparent why one area can be manipulated and another area cannot. If you don’t understand the differences, ask NRCS for clarification. And here’s a link to the Federal Register Conservation Compliance Rules and Regulations.

Options for wetlands: Grow healthy soil

“If you have a field or area of the field designated as a wetland, you can continue to farm it, as long as you don’t alter the drainage system to improve drainage,” Zimprich says. “Wetlands may also be entered into the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program, a USDA program that compensates owners for creating, restoring and enhancing wetlands.” Zimprich adds that wetlands that have been restored, enhanced, or created may qualify for wetland mitigation bank credits, an arrangement where owners who restore and develop wetlands may sell credits to wetlands owners who alter wetlands with unfavorable wetland function impacts, who pay into the bank.

Zimprich believes there’s an option in the Prairie Pothole Region that can dramatically affect the amount of runoff and standing water in cropland fields. “Most farmers who don't have healthy soils aren’t really thinking about how their upland soils impact the amount of water that runs off into potholes and depressional areas. I encourage them to consider building healthier soils. It’s an option that’s very much underused, but it could have a big impact,” Zimprich says. “Regenerated, healthy soils encourage rainfall to infiltrate into the soil, where it can be used by crops, instead of running off running off the field or standing in the field during the early growing season.

To find more #wetland stories by Corn+Soybean Digest, check out this gallery.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like