Think differentMark Riechers and his son Joe raise corn, soybeans and cattle on rolling slopes near Darlington in southwestern Wisconsin’s Driftless Area. Their erodible loess soils have been in continuous no-till for more than 20 years. After two decades without being disturbed, the soil is rich with what Mark calls “dirt critters,” the beneficial organisms that build soil structure and tilth. “Because we don’t disrupt the soil structure with tillage, it can take a lot of water,” he says.As a result of their farming practices, which also include grass waterways and multiple thin applications of solid manure, just 2% of annual rainfall ran off the Riechers’ farm, according to 7 years of monitoring by the University of Wisconsin Discovery Farms. Sediment losses averaged about 300 pounds per year, or 3% of NRCA “tolerable” loss. “It’s not just no-till,” Mark says, “it’s a combination of things.”

December 16, 2013

Intense rainstorms stripped fertile soil from unprotected farm fields across the Corn Belt last spring. Parts of east-central and northwest Iowa lost as much as 24 tons of topsoil per acre in May, according to Daily Erosion Project estimates. “It’s been pretty dramatic,” says Matt Helmers, Iowa State University Extension biosystems engineer. Even in fairly flat areas, “we’ve seen a lot of ephemeral gully erosion.”

Richard Cruse, director of the Iowa Water Center, adds, “Heavy rains came at the worst time this year, when nothing was planted and there was no surface cover.” Many grass waterways, which slow water flow, have been torn out in recent years, and “many others are degraded or not functioning well. This spring shows what can happen as a result.”

The damage underscores the need for conservation practices that protect the soil and slow down water flow during storms, says Dennis Frame, University of Wisconsin Discovery Farms director. “This is a perfect year for farmers to evaluate their conservation programs. You can really see where you should have a grass waterway or buffer strips.”

To minimize future losses, Frame says, understand when and where runoff and soil erosion are most likely to occur, and how you can lower their risk.

Erosion factors are listed below along with erosion risk.

1. Late winter and spring

Risk - Up

Late winter and spring are the most dangerous seasons for runoff and soil erosion. Rapid snowmelt, rain on frozen ground, rain on soils already saturated from melting snow, lack of a crop canopy — all these factors make the soil more susceptible to damage than at any other time of year, Frame says.

Late winter and spring accounted for about 80% of annual runoff, according to 100 site-years of Wisconsin farms’ water, nutrient and soil loss monitoring by the University of Wisconsin. Half of annual runoff occurred in February and March, and an additional one-third in May and June.

2. Structures that slow water flow

Risk - Down

Ephemeral gullies form when rainwater flowing over a field concentrates into narrow channels, which then transport field runoff laden with soil and nutrients. When closed with tillage, they reappear with the next big rainstorm.

One of the best ways to halt ephemeral gully erosion is to plant grass waterways in areas of concentrated flow, Frame says. “Grass waterways are critical,” especially on long slopes with clay soils. When you evaluate this spring’s erosion toll, “The first thing you should think about is, do you have adequate grass waterways? Are they big enough? Are they in the right place?”

Sediment-control basins or dams placed across the channel are also good at slowing down water, he says, lowering its erosive force, and allowing soil to drop out. Water pools briefly behind these earthen berms — some of which are broad enough to be farmed over.

Another effective way to slow water flow and soil loss is planting vegetative buffer strips in strategic places within cropped fields or at the foot of slopes.

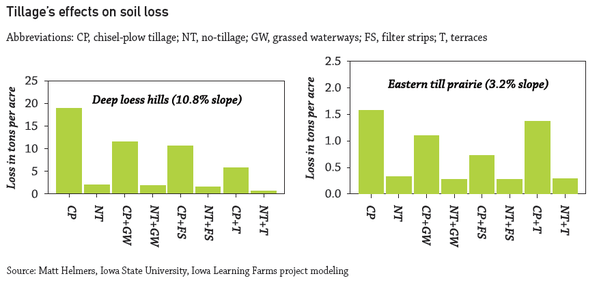

Helmers leads research on the use of “prairie filter strips” on 6-10% slopes in central Iowa. Planting strips of grasses, forbs and legumes at the bottom of sloping no-till corn and soybean fields trapped 96% of sediment, he says. (See http://bit.ly/STRIPs for more information.) “Prairie filter strips could be even more effective in more intensive tillage systems such as chisel plow,” Helmers says.

3. Intense rainstorms

Risk - Up

Intense, 5- or 6-inch rain events in parts of Illinois this spring caused residue movement and soil erosion, says Mike Plumer, Illinois Council of Best Management Practices. Conservation practices and no-till significantly reduced the impact of these rains, he says, but the intensity caused erosion even on farms with good conservation practices.

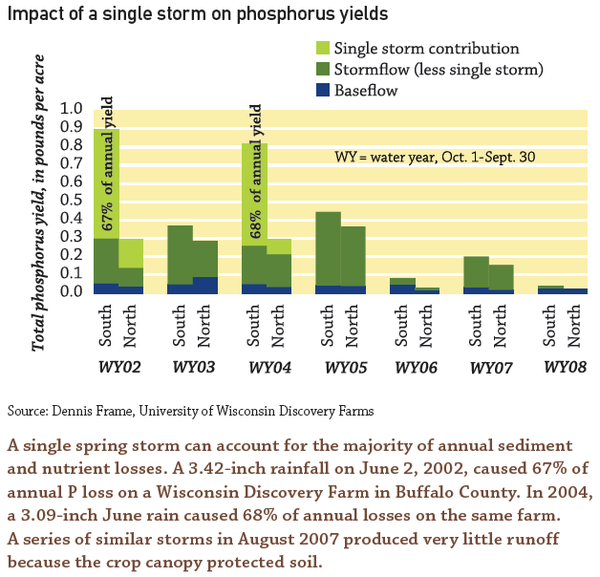

It was the same in Southeast Minnesota and other Corn Belt areas. “Climate science is pointing to more spring seasons like this one, and more intense rainfall events,” says Tim Radatz, research specialist for the Minnesota Agricultural Water Resource Center. One heavy downpour on unprotected soil can cause the majority of annual soil and nutrient losses. “This is really important when we look at ways to reduce runoff.”

Adds Frame, “You can’t control big storms, but you can design and implement farming systems that provide as much protection as possible from those storm events. You can plan for 25-year, 24-hour storms.”

4. Saturated soil

Risk - Up

Soil moisture influences infiltration rates. “On saturated soil, rain will run off just as it does on frozen ground,” Frame says.

Wisconsin Discovery Farms’ monitoring found that when field soil moisture was over 35%, runoff occurred with as little as one-quarter inch of rain. On dry soils under 25% moisture, it usually took 2 inches to produce a runoff event. When soil moisture was between 25% and 35%, a three-quarters-inch rain was enough to cause runoff.

If you use liquid manure, pay close attention to that intermediate range, Radatz says: 13,000 gallons of manure equals about one-half in. of rain. On soil at 25% moisture, the application could bump up the total moisture so that a rain soon after would run off, carrying your nutrients and soil with it.

5. Surface cover

Risk - Down

You can’t control your farm’s soil type, slope, or rainfall timing and intensity — all factors that affect erosion rates. “But you can control how you protect the soil surface,” Helmers says. Reducing or eliminating tillage is the best way to keep your soil in place, he says. On erodible fields, no-till can cut soil loss by up to 90%, according to Iowa Learning Farms Project models.

Illinois farmers are embracing reduced tillage and cover crops to prevent erosion and improve soil quality and infiltration, Plumer says. More than 80% of the state’s soybeans are no-till; fall chisel plowing has decreased, and many Illinois growers have shifted to shallow vertical tillage, which minimizes soil disturbance and leaves a protective residue cover on the soil, Plumer says.

He also sees more cover crop adoption, including cereal rye, ryegrass, oats, oilseed radish and mixtures. Despite the agronomic and management challenges, some 200,000 acres of Illinois cropland were planted with cover crops last fall, Plumer estimates. “Cover crops pretty well eliminated erosion in March and April.”

6. Improved tile drainage

Risk - Down

Tile drainage reduces surface runoff and soil loss, and allows farmers to use less tillage. “Many fields would benefit from tile to decrease channeling and ponding,” Frame says. Older concrete or clay tiles often have cracks or leaks that leak significant amounts of sediment and phosphorus, he says. The same is true of systems with open surface inlets. Older tile systems may also have undersized mains that limit drainage capacity. “So we need to update our older tile systems.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like